There has been a rapid rise in interest in contemporary African art over the past few years, with major survey shows from Brazil to France, new museums springing up in Marrakech and Cape Town and the ever-expanding 1-54 art fair, as well as attention from the big auction houses. Coming hot on the heels of this trend is the first US survey of the Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez (1948–2015) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which offers a fresh approach to this visionary artist. Kingelez, who produced wondrous urban models with found magazines and product packaging, was not simply an artist who created proverbial castles in the air. As the artist himself said: “Without a model, you are nowhere.”

Featuring work that dates from the early 1980s through to the end of Kingelez’s life, the exhibition tells the story of how these models addressed urban, social and economic concerns. “While he knew they were not likely to be realised in his lifetime—in fact, he said we were not ready for them—they were certainly a proposal, a real, tangible proposal for how we might live in the tomorrow,” says the exhibition’s curator, Sarah Suzuki.

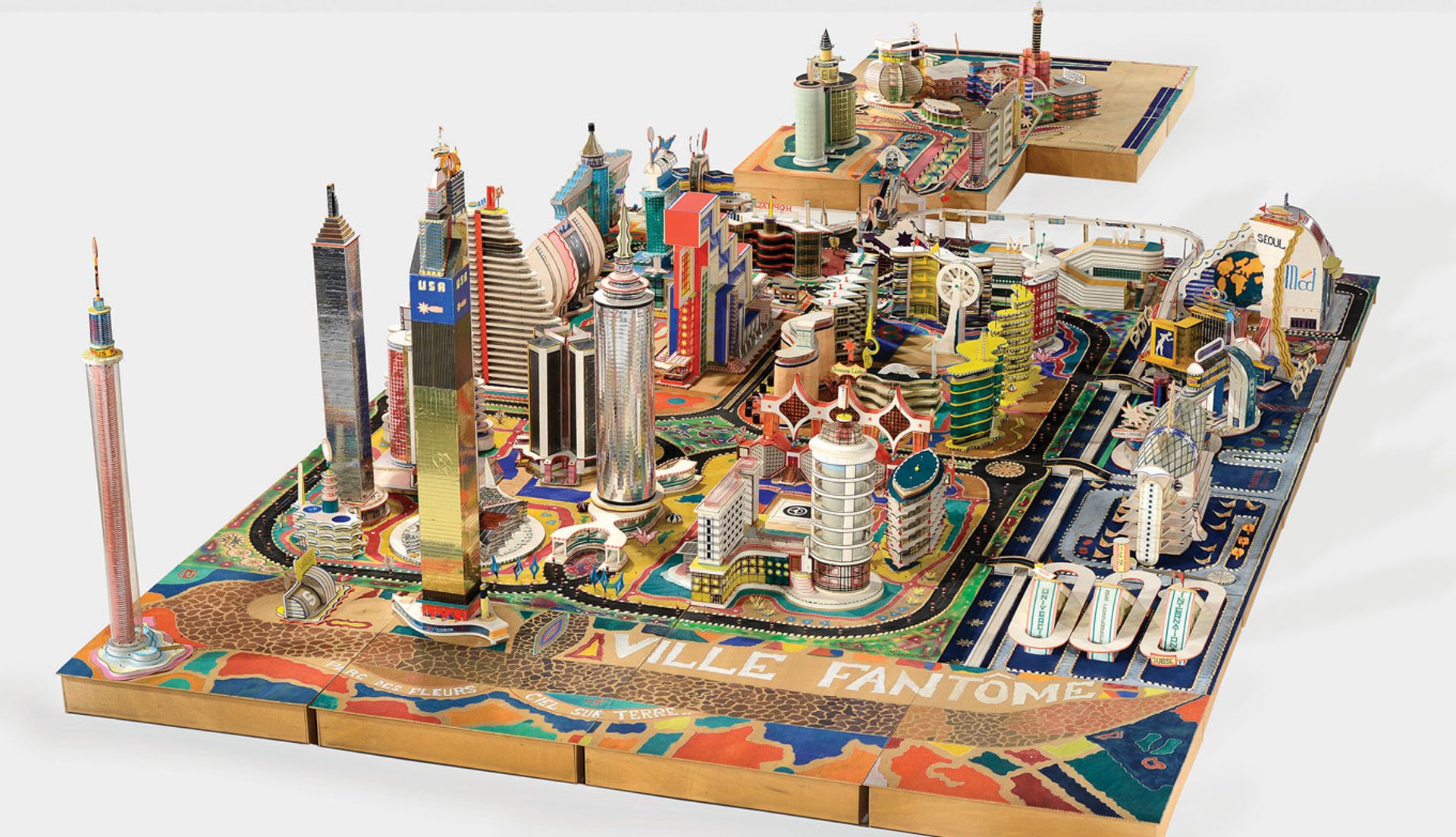

Ville Fantôme (1996) is accompanied by a virtual-reality component, enabling visitors to inhabit the structure Bodys Isek Kingelez; Photo: Maurice Aeschimann; courtesy of CAAC, The Pigozzi Collection

Ville Fantôme (1996), for example, is a city without police or jails. The work is accompanied by a virtual reality component that enables visitors to inhabit the structure. According to Suzuki, this allows people to see “just how holistically these [models] were conceived”. She notes that the level of detail is more than the naked eye can detect (particularly at a museum with boundaries and guards).

Before becoming an internationally exhibited artist in the late 1980s, Kingelez worked as a secondary school teacher in Kinshasa in what was then Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). He started to craft his first paper sculptures with scissors, glue and Gillette razors, which initiated a practice of using found materials. “It was out of necessity he was using those materials, but he always chose them with the utmost care,” explains the curator. Owing to the sheer level of detail and skill he demonstrated in these early works, the National Museum of Zaire (now the National Museum of Kinshasa) recruited the artist as a conservator of tribal masks.

Bodys Isek Kingelez's Ville de Sète 3009 (2000) Pierre Schwartz ADAGP; courtesy Musée International des Arts Modestes (MIAM), Sète

“In those years he was able to develop a clearer picture of what he wanted to do with his own practice, which was in many ways to make a distinction between the traditional work for which Congo had become known and the work that he was making,” Suzuki says.

Kingelez’s experiences in Kinshasa certainly informed his work as well. He lived in the shadow of Belgian colonial architecture and the ambitious structures erected by Mobutu Sese Seko after he came to power in 1965 as Kinshasa’s population grew rapidly, outpacing its infrastructural capacities. “What he’s often doing is positing a scenario where society is perfectly functioning,” says Suzuki of the work. “[And] all the resources are available.”

The exhibition’s main sponsor is Allianz.

• Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 26 May-1 January 2019