Coming days after yet another mass shooting in the US—this time at a high school in Santa Fe, Texas, where ten people were killed—an exhibition featuring art formed from dismantled firearms opened in Oakland, California on Tuesday (22 May). The Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, together with the Robby Poblete Foundation, organised the show and commissioned local artists to transform hundreds of guns the DA’s office has confiscated over the years.

The exhibition replicates another currently on view at the Temple Art Lofts in Vallejo (until 29 June). Both are part of the Poblete Foundation’s Art of Peace initiative, which seeks to remove guns from street circulation, transform them into instructive art and call attention to the types of daily shootings that occur in low-income and minority neighbourhoods. “My frustration is that yes, when there is a mass shooting, it rightly deserves the coverage it gets. But if you look at the totality of everyday shootings in these neighbourhoods, it’s a mass shooting everyday, and we just don’t see it [presented] that way,” says the foundation's founding director, Pati Navalta. “What I’m trying to do with Art of Peace is raise awareness about that.”

After her 23-year-old son Robby was shot and killed in Vallejo in 2014—with a firearm that was stolen from a home and sold illegally on the street—Navalta launched the foundation and a gun buy-back programme last year, having learned that most violent crime is committed with stolen weapons. “I wanted to come up with a way to get those unwanted firearms out of circulation and prevent them from falling into the wrong hands,” she explains. “Then I started to think about what happens to the guns after they’re collected.” At the time of his death, Robby Poblete was training to weld and was eagerly planning art projects with scrap metal; the art commissions honour his unrealised projects.

The pop-up Oakland exhibition, up for a month at 9th and Washington Streets, emerged after the DA’s office, seeking a more environmentally friendly means of emptying its evidence lockers, learned of the foundation and sought to duplicate its project. It includes work from six artists, such as Kevin Byall, who has created a stand-alone double-helix sculpture. “Made out of six different repurposed gun parts, it is designed to convey how engrained we are to violence and the difficult reprogramming we face to change that construct,” the artist explains in a statement about the work.

Simorgh by the Iranian immigrant artist Keyvan Shovir is in memory of his friends Soroush and Arash Farazmand, the founders of the rock band The Yellow Dogs, who were shot and killed in Brooklyn four years ago Photo: Gary Cullen

“To pick up a grip from a revolver and hold it in your hand and think about the history it could possibly contain, and the misery it potentially inflicted, it's really haunting,” says Andrew Johnstone, the Alameda County Art Commissioner, who is shepherding the Oakland project. “The real way to move the needle on this issue is culture change,” he adds. “This is what art does best.”

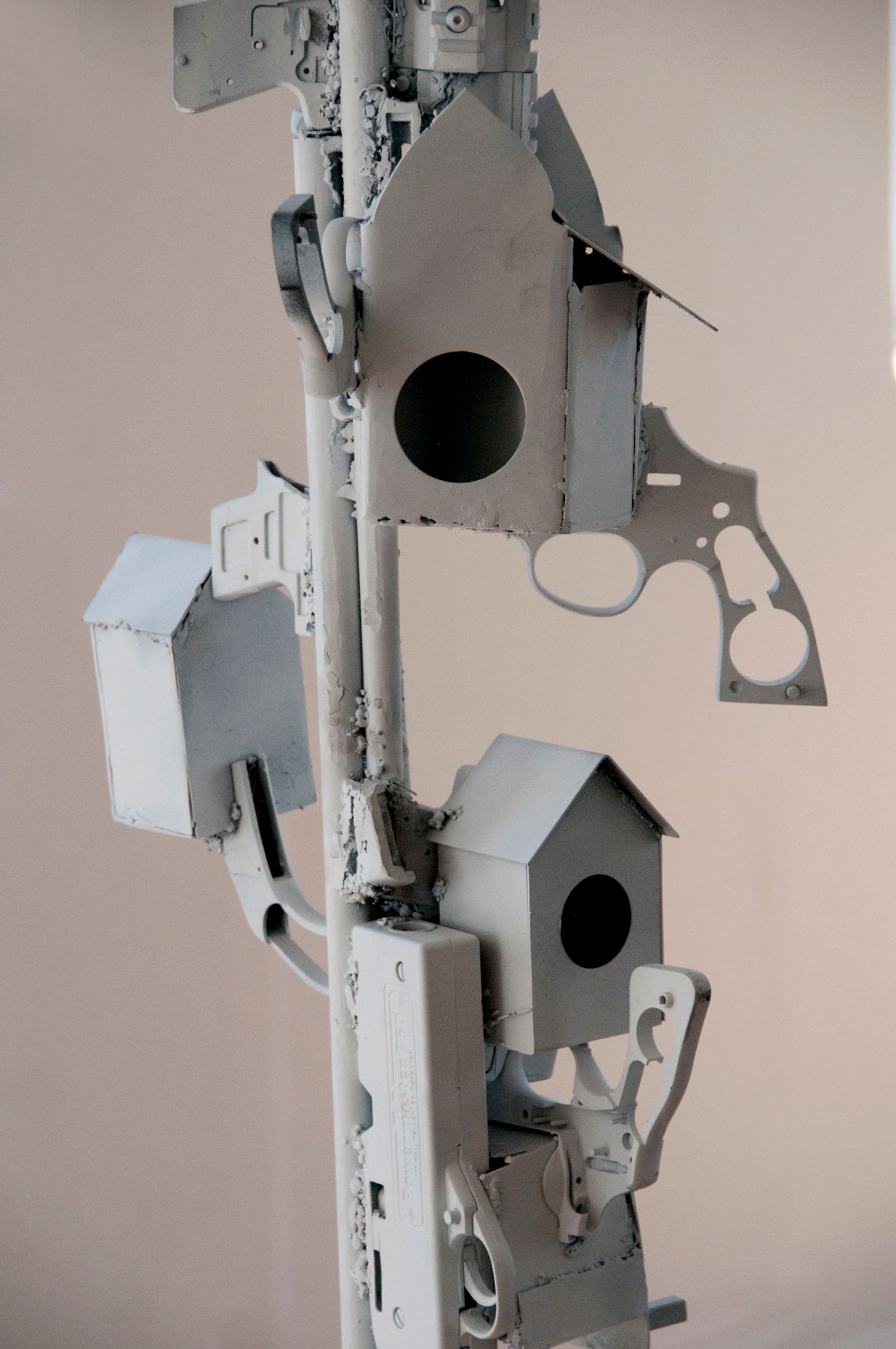

In the Vallejo show, many of the artists have personally suffered from gun violence. The San Francisco-based Keyvan Shovir, for example, who immigrated to the US from Iran in 2011, has created a bird house sculpture installation from the stripped down gun parts to celebrate his two friends, the brothers Soroush and Arash Farazmand, founders of the Iranian rock band The Yellow Dogs, who were shot and killed in Brooklyn four years ago. “These events affected my creative community causing some to abandon their art practice,” reads the artist’s statement. “As an Iranian immigrant, we are witnesses of the war between Iran and Iraq. Finding peace and hope was one of our motivations to move out of our home nation.”