“It’s a bad time to be a white male artist”, quips the art advisor Lisa Schiff, but the joke rang true at the evening sales of post-war and contemporary art at Phillips and Christie’s on 17 May. The results confirmed the pattern set at Sotheby’s the previous night and in record-setting day sales this week: the market is strong, expanding and in search of freshness. “There is an appetite and a hunger for great things”, says the advisor Abigail Asher, of Guggenheim Asher, “but the energy feels different.”

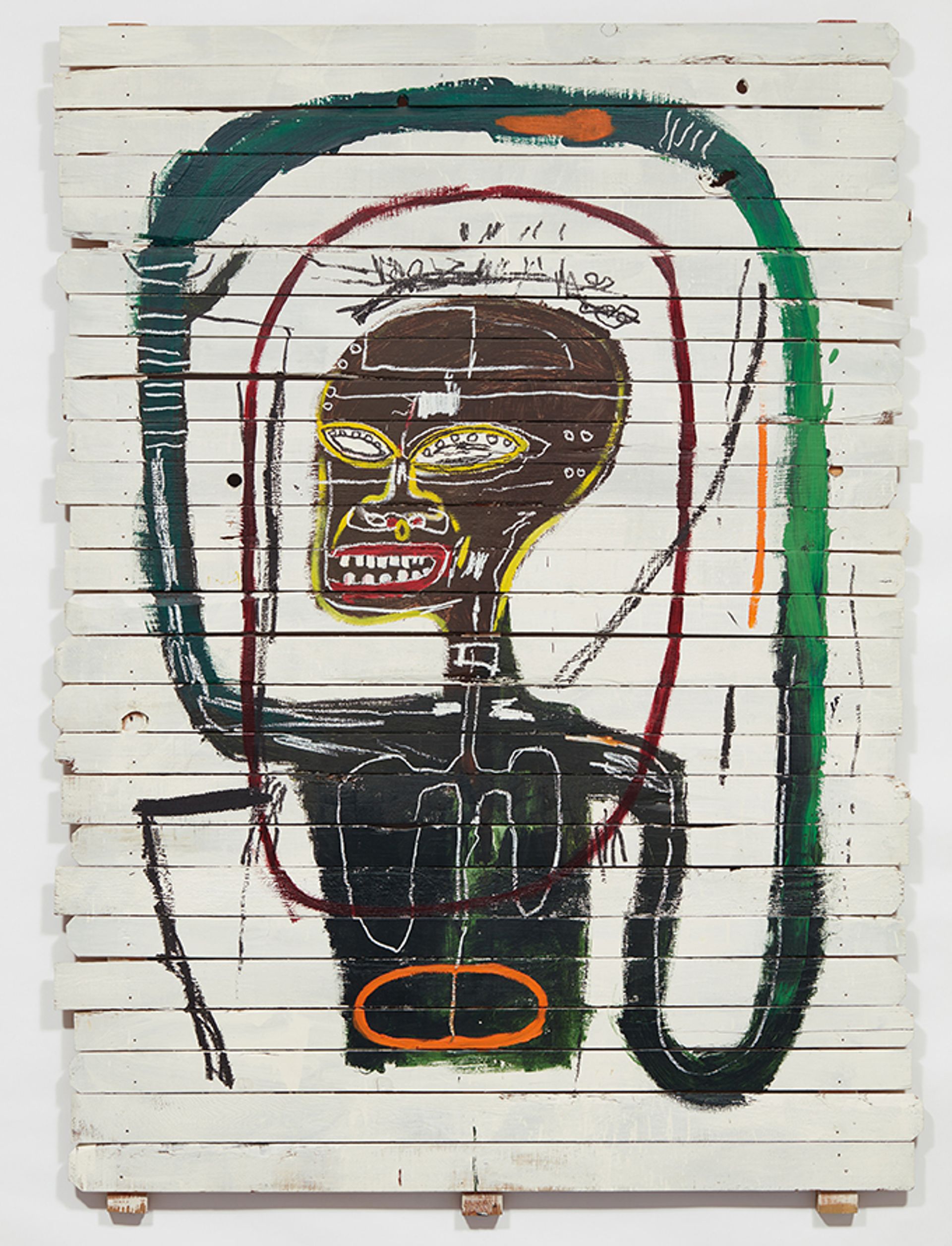

Jean-Michel Basquiat's Flexible (1984), sold for $45.3m at Phillips Courtesy of Phillips

Basquiat steals show at Phillips

Phillips, commencing the evening with its 20th century and contemporary auction, came close to beating its best-ever result, set just a few months ago in London, with a total of $131.6m. The indisputable star was Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Flexible (1984), painted on a 10ft tall section of wooden fencing and consigned by the artist’s estate. Estimated in the region of $20m, the lot opened to a shouted bid of $30m, and after several minutes eventually sold at $45.3m (with fees), sold to a client on the phone with Phillips’ deputy chair, Miety Heiden.

Bidders showed keen interest in Cory Arcangel’s kaleidoscopic Photoshop CS […] (2011), which made $399,000 (est $150,000-$200,000), a record, as was the $2.3m paid for Pat Steir’s large-scale oil, Elective Affinity Waterfall (1992, est $600,000-$800,000), more than double the artist’s previous high of $975,000.

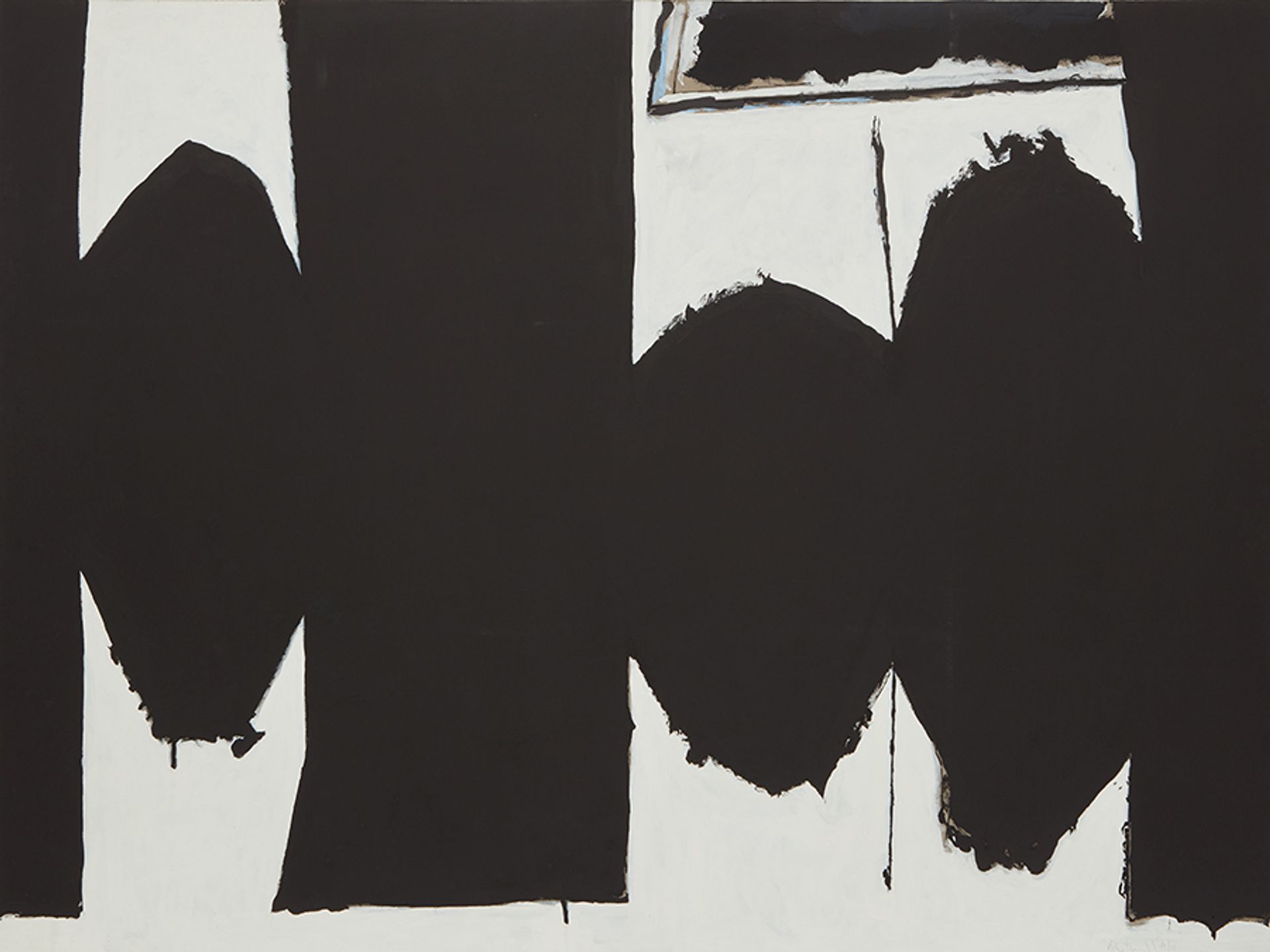

Robert Motherwell's At Five in the Afternoon (1971), sold for $12.7m at Phillips Courtesy of Phillips

Robert Motherwell’s At Five in the Afternoon (1971)—an anticipated highlight of the sale as the first work in the artist’s celebrated Elegy to the Spanish Republic series—brought $12.7m (with fees), narrowly meeting its $12m low estimate but nonetheless compounding the artist’s previous record of $3.7m. “We lifted Motherwell into a new price category”, says Phillips chairman Cheyenne Westphal, “where we feel he should be.”

The auction house had less luck with its section of Dusseldorf school painters. Sigmar Polke’s Stadtbild II (City Painting II) (1968) and a Gerhard Richter squeegee work, Abstraktes Bild (811-2) (1994), fell flat on estimates of $12m to $18m (another Polke was withdrawn prior to the sale). But there were just three buy-ins in a slate of 35 works, and the auction house’s chief executive, Edward Dolman, said he was “delighted” with the sale’s progress, up 20% from last year’s total.

Bacon tops Christie’s contemporary offering

Swivelling across Fifth Avenue to Rockefeller Center, the crowd seemed to lose some energy in the transfer, but Christie’s 64-lot post-war and contemporary auction realised $397.2m, just north of last year's result.

The second lot, David Hockney’s oil on canvas Antheriums (1995, est $2.5m-$3.5m), sparked a three-way tussle that landed at $5.6m (with fees), a coda to the strong prices seen for Hockney elsewhere this week. But it was lot six that opened the floodgates—Joan Mitchell’s sunny, heavily daubed canvas Blueberry (1969; est $5m-7m), painted the year after Mitchell moved from Paris to the countryside of Vetheuil, which signalled a fertile period for the artist, at least seven bidders were in the chase, including contestants in the room and on the phone with Christie’s Asia head Rebecca Wei, before the hammer finally fell at $14.5m, or $16.6m with fees, a new record for the late artist.

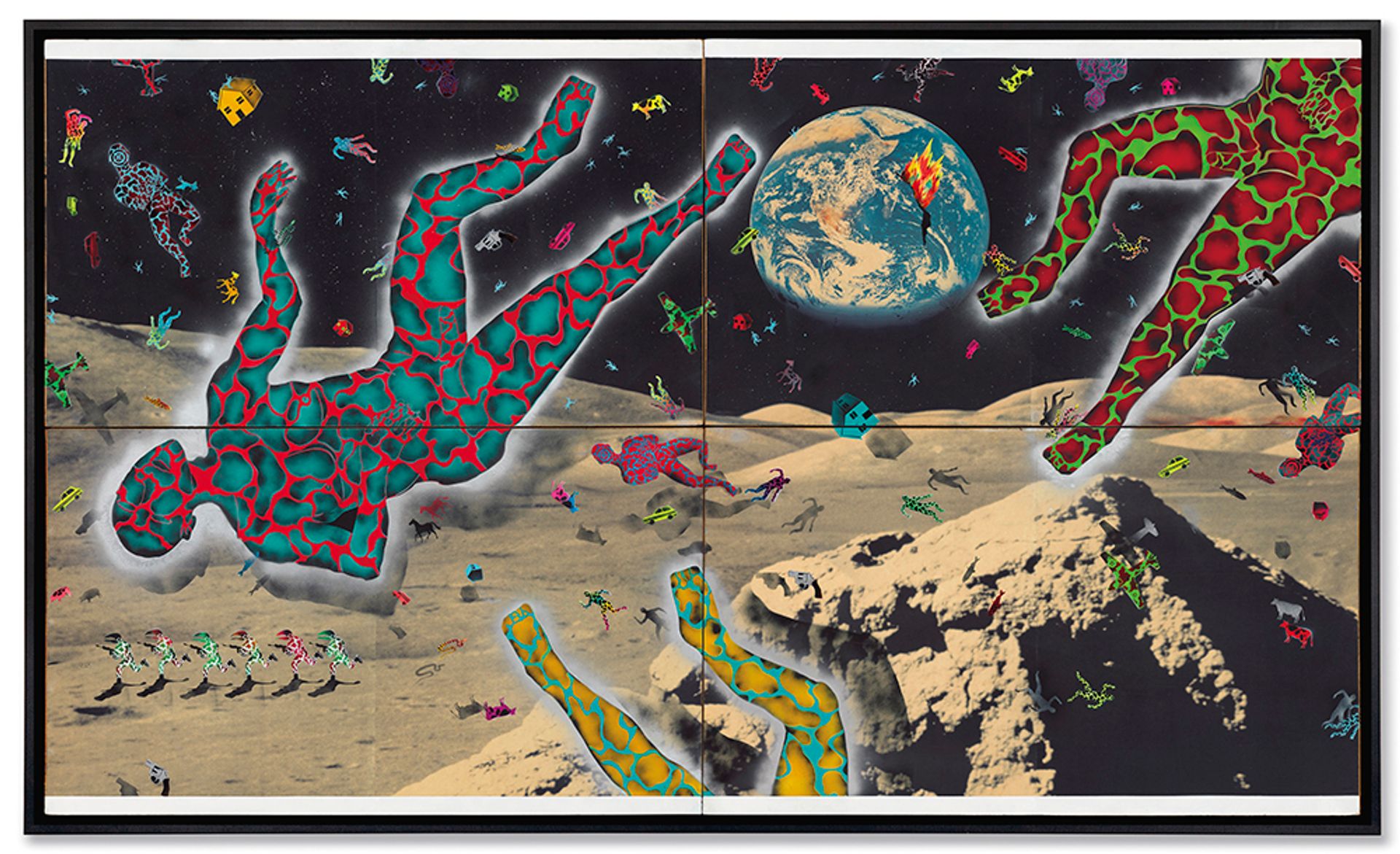

David Wojnarowicz's Science Lesson (1982-83), sold for $708,500 at Christie's Courtesy of Christie's Images LTD

Immediately after came Francis Bacon’s Study for Portrait (1977), an anguished portrayal of the artist’s lover, George Dyer, who committed suicide in 1971, in his studio. As head of sale Ana Maria Celis noted in advance of the auction, this the only full-length painting of Dyer to appear on the auction block since 2014, when Portrait of George Dyer Talking (1966) made $70.2m at Christie’s London. This one, estimated around $30m, rang up $49.8m with fees, offered by a determined client on the phone with Renato Pennisi of Christie’s Milan. It was the highest price of the week for a contemporary work.

The Bacon was trailed by Andy Warhol’s silvered Double Elvis (Ferus Type) (1963), which had sold for $37m from Steve Wynn at Sotheby’s in 2012 and went for the same price to dealer Brett Gorvy, of Lévy Gorvy, on his cell phone in the room. He and business partner Dominique Lévy wound up bidding against each other on the priciest Richard Diebenkorn of the night, Ocean Park #126 (1984), which lodged just north of its high estimate at $23.9m with fees. The work was part of a passel of 12 Diebenkorns consigned from the collection of Donald and Barbara Zucker and sold to benefit their family foundation. Demand largely met that volume, though with a preference for the later abstractions over early figurative works. Altogether, the Zucker lots contributed $43m to the total.

Richard Diebenkorn's Ocean Park #126 (1984), sold for $23.9m at Christie's Courtesy of Christie's Images LTD

It was not a great night for the postwar and contemporary titans who have dominated the category in recent years. A Donald Judd wall stack, a Dan Flavin “monument” for V Tatlin, and a sombre Clyfford Still were among the scant number of buy-ins. Works by Jeff Koons, Yves Klein, Damien Hirst, Christopher Wool, and Agnes Martin sold but on the low end of their estimates.

More enticing were works by David Wojnarowicz, whose four-panel collage Science Lesson (1982-83) more than doubled his previous auction record with a final price of $708,500; Morris Louis, whose Devolving (1959-60) leap-frogged the record set earlier in the evening by Number 4-32 (1962) to land at $5.7m; and Nicolas de Stäel, whose harmonious Nu debout (1953; est $7.5m-$9.5m) clocked in at an artist-record $12.1m. Sara Friedlander, the international director of post-war and contemporary art, said after the sale: “What we see time and again is people responding to things that are fresh to market that have been held and loved”.

“Both nights were very strong”, says advisor Baird Ryan, of Morgan Walker Fine Art. “It’s hard to walk away from the week and not consider a new price level for artists like Mitchell, Louis, Diebenkorn and De Kooning.” He acknowledges “a shift in tastes and a secular mood” driving a correction to the canon, but says there is also “a rotation in the market” away from certain names. “A few years ago, Richter was currency, and in a few years I’m sure he will be again”, Ryan says. Until then, though, the smart money is elsewhere.