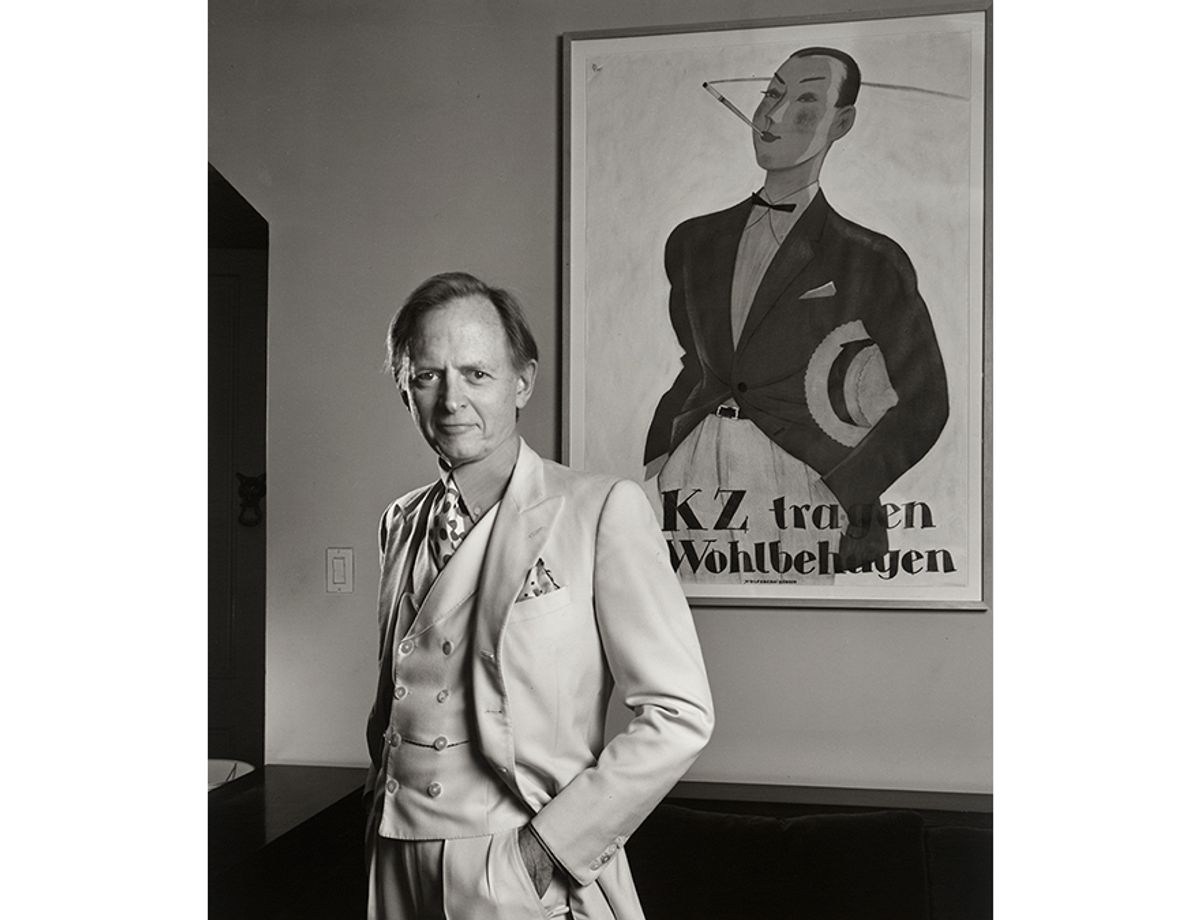

The gymnastic novelist and journalist Tom Wolfe, who died on Tuesday (16 May) in New York, aged 88, was a popular, savvy, if also controversial commentator on art (as well as a sharp dresser). In The Painted Word (1975), his nose-thumbing critique of Modern art, its critics and collectors, Wolfe is certainly glib, full of generalisations and questionable assumptions. And yet his underlying thesis, that visual art had degenerated into chic art theory and was otherwise meaningless, expressed what many people felt, and continue to feel, at the gates of the rarefied art world—and here was Wolfe, a PhD from Yale, saying it. Upon its publication, the academic historian and critic Rosalind Krauss famously panned the book as “like a really bad, MSG-headache-producing, Chinese lunch”. But of course, such a lunch carries a certain kind of pleasure, too. Below is an excerpt from The Painted Word, reprinted with permission from the publishers Farrar, Straus and Giroux and Picador.

People don't read the morning newspaper, Marshall McLuhan once said, they slip into it like a warm bath. Too true, Marshall! Imagine being in New York City on the morning of Sunday, April 28, 1974, like I was, slipping into that great public bath, that vat, that spa, that regional physiotherapy tank, that White Sulphur Springs, that Marienbad, that Ganges, that River Jordan for a million souls which is the Sunday New York Times. Soon I was submerged, weightless, suspended in the tepid depths of the thing, in Arts & Leisure, Section 2, page 19, in a state of perfect sensory deprivation, when all at once an extraordinary thing happened:

I noticed something!

Yet another clam-broth-colored current had begun to roll over me, as warm and predictable as the Gulf Stream . . . a review, it was, by the Times's dean of the arts, Hilton Kramer, of an exhibition at Yale University of "Seven Realists," seven realistic painters . . . when I was jerked alert by the following:

"Realism does not lack its partisans, but it does rather conspicuously lack a persuasive theory. And given the nature of our intellectual commerce with works, of art, to lack a persuasive theory is to lack something crucial—the means by which our experience of individual works is joined to our understanding of the values they signify."

Now, you may say, My God, man! You woke up over that? You forsook your blissful coma over a mere swell in the sea of words?

But I knew what I was looking at. I realized that without making the slightest effort I had come upon one of those utterances in search of which psychoanalysts and State Department monitors of the Moscow or Belgrade pres are willing to endure a lifetime of tedium: namely, the seemingly innocuous obiter dicta, the words in passing, that give the game away.

What I saw before me was the critic-in-chief of The New York Times saying: In looking at a painting today, "to lack a persuasive theory is to lack something crucial." I read it again. It didn't say "something helpful" or "enriching" or even "extremely valuable." No, the word was crucial.

In short: frankly, these days, without a theory to go with it, I can't see a painting.

Then and there I experienced a flash known as the Aha! Phenomenon, and the buried life of contemporary art was revealed to me for the first time. The fogs lifted! The clouds passed! The motes, scales, conjunctival bloodshot, and Murine agonies fell away!

All these years, along with countless kindred souls, I am certain, I had made my way into the galleries of Upper Madison and Lower Soho and the Art Gildo Midway of Fifty-seventh Street, and into the museums, into the Modern, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim, the Bastard Bauhaus, the New Brutalist, and the Fountainhead Baroque, into the lowliest storefront churches and grandest Robber Baronial temples of Modernism. All these years I, like so many others, had stood in front of a thousand, two thousand, God-knows-how-many thousand Pollocks, de Koonings, Newmans, Nolands, Rothkos, Rauschenbergs, Judds, Johnses, Olitskis, Louises, Stills, Franz Klines, Frankenthalers, Kellys, and Frank Stellas, now squinting, now popping the eye sockets open, now drawing back, now moving closer—waiting, waiting, forever waiting for . . . it . . . for it to come into focus, namely, the visual reward (for so much effort) which must be there, which everyone (tout le monde) knew to be there—waiting for something to radiate directly from the paintings on these invariably pure white walls, in this room, in this moment, into my own optic chiasma. All these years, in short, I had assumed that in art, if nowhere else, seeing is believing. Well—how very shortsighted! Now, at last, on April 28, 1974, I could see. I had gotten it backward all along. Not "seeing is believing," you ninny, but "believing is seeing," for Modern Art has become completely literary: the paintings and other works exist only to illustrate the text.

Like most sudden revelations, this one left me dizzy. How could such a thing be? How could Modern Art be literary? As every art-history student is told, the Modern movement began about 1900 with a complete rejection of the literary nature of academic art, meaning the sort of realistic art which originated in the Renaissance and which the various national academies still held up as the last word.

Literary became a code word for all that seemed hopelessly retrograde about realistic art. It probably referred originally to the way nineteenth-century painters liked to paint scenes straight from literature, such as Sir John Everett Millais's rendition of Hamlet's intended, Ophelia, floating dead (on her back) with a bouquet of wildflowers in her death grip. In time, literary came to refer to realistic painting in general. The idea was that half the power of a realistic painting comes not from the artist but from the sentiments the viewer hauls along to it, like so much mental baggage. According to this theory, the museum-going public's love of, say, Jean François Millet's The Sower has little to do with Millet's talent and everything to do with people's sentimental notions about The Sturdy Yeoman. They make up a little story about him.

What was the opposite of literary painting? Why, Part pour Part, form for the sake of form, color for the sake of color. In Europe before 1914, artists invented Modern styles with fanatic energy—Fauvism, Futurism, Cubism, Expressionism, Orphism, Suprematism, Vorticism—but everybody shared the same premise: henceforth, one doesn't paint "about anything, my dear aunt," to borrow a line from a famous Punch cartoon. One just paints. Art should no longer be a mirror held up to man or nature. A painting should compel the viewer to see it for what it is: a certain arrangement of colors and forms on a canvas.

Artists pitched in to help make theory. They loved it, in fact. Georges Braque, the painter for whose work the word Cubism was coined, was a great formulator of precepts:

"The painter thinks in forms and colors. The aim is not to reconstitute an anecdotal fact but to constitute a pictorial fact."

Today this notion, this protest—which it was when Braque said it—has become a piece of orthodoxy. Artists repeat it endlessly, with conviction. As the Minimal Art movement came into its own in 1966, Frank Stella was saying it again:

"My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there is there. It really is an object . . . What you see is what you see. "

Such emphasis, such certainty! What a head of steam—what patriotism an idea can build up in three-quarters of a century! In any event, so began Modern Art and so began the modern art of Art Theory. Braque, like Frank Stella, loved theory; but for Braque, who was a Montmartre bono of the primitive sort, art came first. You can be sure the poor fellow never dreamed that during his own lifetime that order would be reversed.

Copyright © 1975 by Tom Wolfe. Published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, LLC. All rights reserved.