After overcoming threats and opposition from Cuban authorities, the inaugural edition of Havana’s alternative #00Bienal ended this Tuesday on a consistently defiant note, with a view towards cracking the country’s strict control of creative production. The organisers see the fact that the 10-day event happened at all as a sign of success. “In the context of current cultural pessimism, the #00Bienal is an achievement,” says the artist Luis Manuel Otero, one of the exhibition’s organisers.

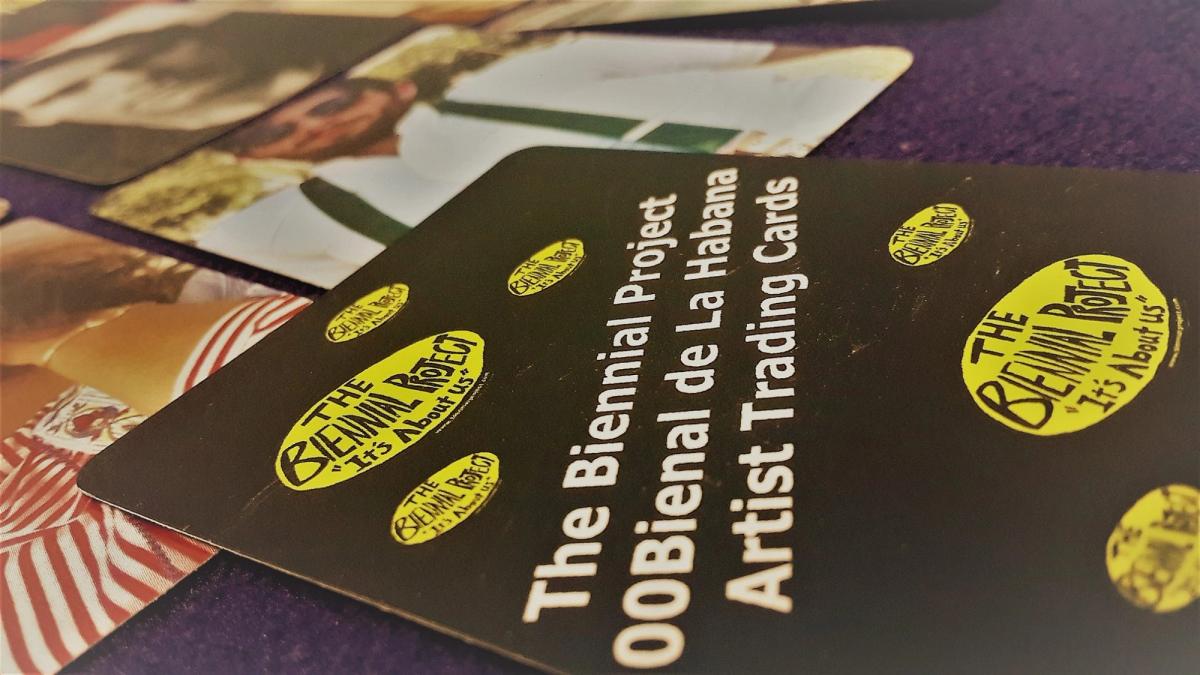

Otero and the curator Yanelys Nuñez Leyva, started planning the independent art exhibition last fall after the official, state-sponsored Havana Biennial was postponed for a second time to 2019, due to lack of resources after hurricanes hit the island. “Six months ago everyone said it was impossible to hold this event because of the resistance and repression of the Cuban State, starting from the Ministry of Culture to the political police (although they are the same apparatus),” he says. “These institutions have centralised culture and politics in a single point, something that has been detrimental to any independent action in Cuba.”

In the lead up to the #00Bienal (5-15 May 2018), Cuban state security reportedly threatened participants and blocked the entry of foreign artists and curators, including the New York-based Cuban writer and artist Coco Fusco. The state-backed Cuba Artists and Writers Union denounced the #00Bienal in a statement, saying it created “a climate propitious to promoting the interests of the enemies of the nation” and used “funds of the mercenary counter-revolution”. The day before the biennial’s opening, the Spanish artist Diego Gil was called into a Cuban immigration office where he was threatened with detention and had his tourist visa revoked, leading him to leave the country. And some Cuban nationals were threatened by a division of Cuba’s ministry of culture with having their artist’s permit revoked if they participated in the independent biennial, while other artists were fined, Nuñez Leyva says.

Such intimidation tactics continued throughout the biennial’s run, with authorities encircling and blocking entry into event spaces and harassing artists. Some participating artists did not show up in the end, Otero told the news channel 14ymedio, but many more remained committed and the biennial marched on. A wide variety of events, performances and exhibitions carried on in multiple locations, including Tania Bruguera’s home in Old Havana, which now hosts the Hannah Arendt Institute for Artivism. This level of resistance shows how the event has helped to “destabilise the rough mechanisms of the Cuban government that discredit [anything that is] truly independent”, Otero says.

“In spite of everything, #00Bienal has been a success because we managed to count on the unity and the collaboration of more than 140 artists and intellectuals, both Cubans and foreigners,” Otero says. “The inevitable union of all these forces makes it possible for the system to change.” Another significant milestone, Otero adds, is the “real work” the biennial achieved in giving visibility to peripheral and outsider artists, such as Alein Somonte, David León, Andrés X, Yasser Castellanos, which was one of the goals of the democratically minded, anti-establishment exhibition.

As for the future, no second edition is planned in Havana, but the organisers say the idea has been floated of developing a similar project with artists in other countries, such as Mexico. “But that is still only at the conversation stage,” Nuñez Leyva says.