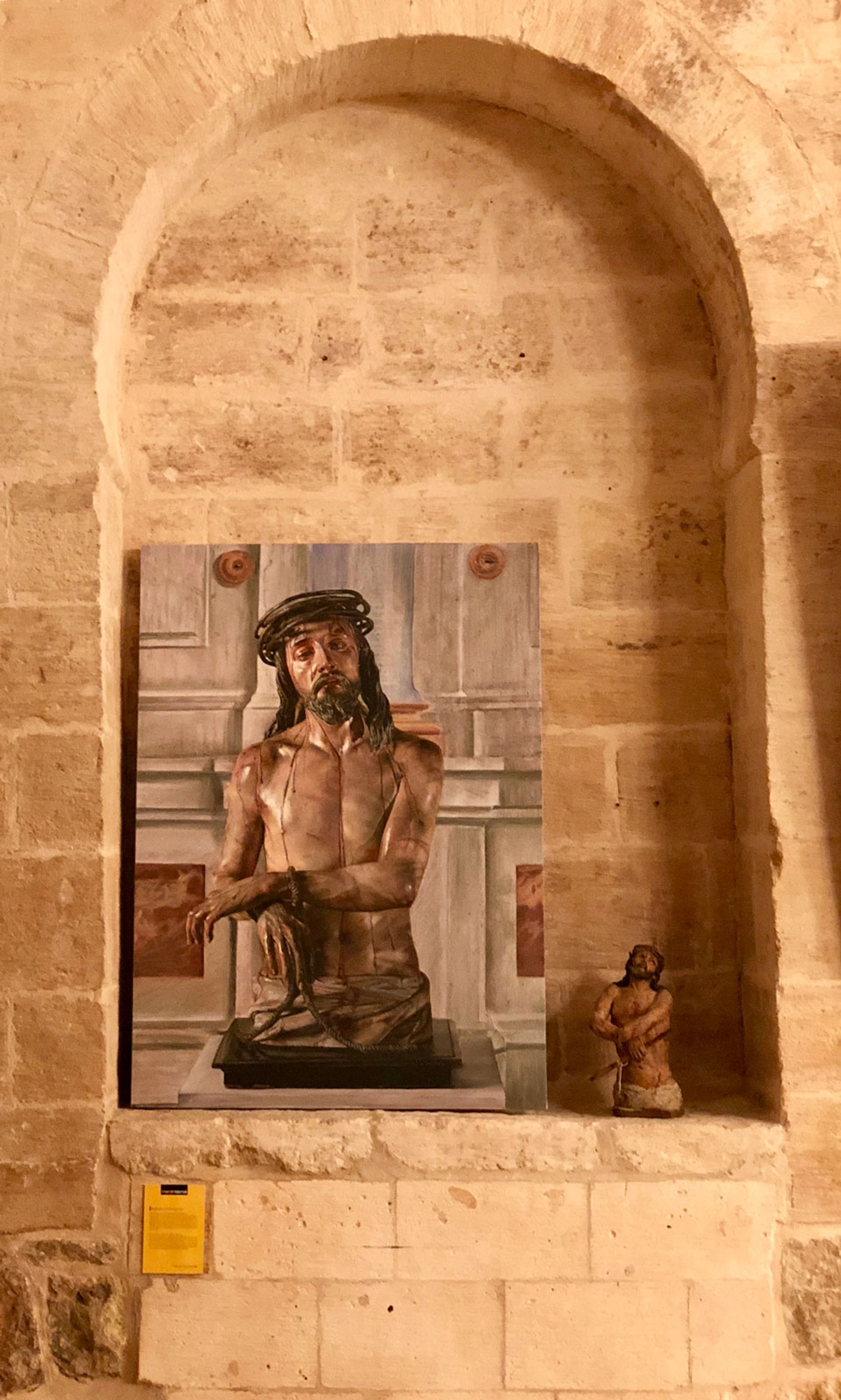

When curators in the Turkish city of Mardin asked a local church to display Taner Ceylan’s hyper-realistic rendition of Pedro de Mena’s 17th-century Christ as the Man of Sorrows, it immediately accepted.

Locked away in the vaults of the Church of the Virgin Mary was a wooden replica of the devotional statue. Made centuries and a world apart, it now sits beside Ceylan’s The Man of Sorrows in a church niche, united for the Mardin Biennial (until 4 June).

“When they showed me the statue, I was awestruck. I had travelled to museums around the world to see it, and it was here all along,” Ceylan says, who had held on to the work with the intent of one day showing it in a house of worship. “This is what’s special about Mardin.”

Taner Ceylan, The Man of Sorrows (2016) Mardin Biennial

Ceylan is one of 50 artists at the biennial, which resumed this month after a three-year pause amid violence across the frontier in Syria and in cities in Turkey’s mainly Kurdish southeast. With the return of relative calm, more than 2,000 art-goers have already visited the fourth edition, titled Beyond Words, since it opened on 4 May.

“Few believed we could endure in this region, and perhaps that’s what showed me that we must,” says Done Otyam, the biennial’s director since its inception in 2010.

The curators Nazli Gurlek, Firat Arapoglu and Derya Yucel lured major Turkish talent like Ceylan and the multimedia artist CANAN, as well as 17 international participants, to work in millennia-old Mardin, a collection of golden limestone buildings perched atop a hill overlooking the Mesopotamian plains. In the hazy distance lies Syria.

The political terrain remains rough. Beyond Words takes place during emergency rule, imposed after a failed military coup in 2016. The government’s subsequent crackdown has jailed tens of thousands, including journalists, scholars and a handful of artists, putting any politically sensitive endeavour in a precarious position.

“We had to consider what we could do in Mardin, where it can be difficult to have a discussion. There is a state of emergency. Beyond Words doesn’t mean we don’t have anything to say, because we do, but we wanted to explore expressing ourselves in other ways,” Gurlek says.

Gurlek curated Body Language, one of the show’s three themes, the other two being Infinite Sight, and Boundaries and Thresholds. The art, including 21 site-specific pieces, sprawls over more than half a dozen historic venues, including a coffee house, a stall at Mardin’s 17th-century bazaar and a former monastery that was converted into prison before it was abandoned.

In a disused bathhouse, CANAN has hung delicate tulle tapestries embroidered with animals, including the locally revered peacock, whose shadows dance across marble walls. They are accompanied by music emitted from the adjacent room in photographer Youssef Nabil’s installation You Never Left, in which the death of a man is an allegory for exile from Egypt.

Yousseff Nabil, You Never Left (2010) Mardin Biennial

The British artist Simon Faithfull traverses continents along the prime meridian in a slideshow and video to question how a Victorian-era geographical marker continues to divide our world. It is on view in a dilapidated mansion that was owned by an Armenian merchant before the German army made it its military headquarters in the First World War.

In a sign of the city’s arts revival, porcelain works by Ai Weiwei are on view in a separate but concurrent show at a Mardin museum whose owners hosted the Chinese superstar in Istanbul earlier this year.

Otyam postponed the 2014 biennial for six months after Islamic State seized swathes of Syrian territory. Then, within weeks of the show wrapping, a peace process between the Turkish government and Kurdish militants collapsed, unleashing clashes that killed thousands and laid waste to nearby towns.

Even in quieter days, putting on a contemporary art show in a far-flung corner of Turkey was not easy. Far from the buzz of Istanbul, whose biennale ranks alongside Venice and Sao Paolo’s, the Mardin Biennial scrapes together funding from a collectors’ initiative and a crowdsourcing website.

“The centre of gravity is no longer in the West; there are different centres and perspectives,” Gurlek says. “We avoided romanticising Mardin or simply imposing outside artists on it. Instead, the work examines our shared human experience.”

Mursel Argunaga, Untitled (2015) Mardin Biennial

Local artist Mursel Argunaga’s Untitled places the disembodied plaster limbs of a father, mother and child on a Turkish carpet in a Crucifixion-like pose to evoke both domesticity and displacement. The collective Merkezkac has released hundreds of polyester scorpions from a nook on an inner wall of the barracks. An everyday invasive threat in Mardin’s arid climate, the outsized arachnids are a reminder that danger lurks around the corner.

This part of the Middle East has always known strife. A century ago, its Christian population was decimated in a wartime genocide, and subsequent decades of poverty and violence have reduced the Church of the Virgin Mary’s congregation to just eight families of various denominations.