The RA250 project, opening on 19 May, is not an ostentatious, spanking-new building in the manner of many recent museum developments. It is principally a conversion and sprucing-up of old buildings: some parts of Burlington House on Piccadilly and most of Burlington Gardens, the building with a chequered history behind the Royal Academy of Arts’ main building. The architect and Royal Academician David Chipperfield has added some new elements, the most important being the Weston Bridge between the two buildings.

Burlington House and Gardens: behind the scenes of the Royal Academy of Arts Hayes Davidson, David Chipperfield Architects

And that physical link is symbolic. The project is about unity, creating a single building that allows for an expanded programme, with more exhibition space in Burlington Gardens, but also a consolidation of previously undervalued or little-seen elements of the Academy’s activities: its rich collections, which will have their first dedicated gallery; the work of the Royal Academicians, who also gain an exhibition space; and the RA Schools, with its lively studios between the two buildings. The RA has many quirky traditions and customs, and here we explore its elaborate structure and some of the people who make up this unique, even eccentric, British institution.

Charles Saumarez Smith Cat Garcia

1) Secretary and chief executive: Charles Saumarez Smith

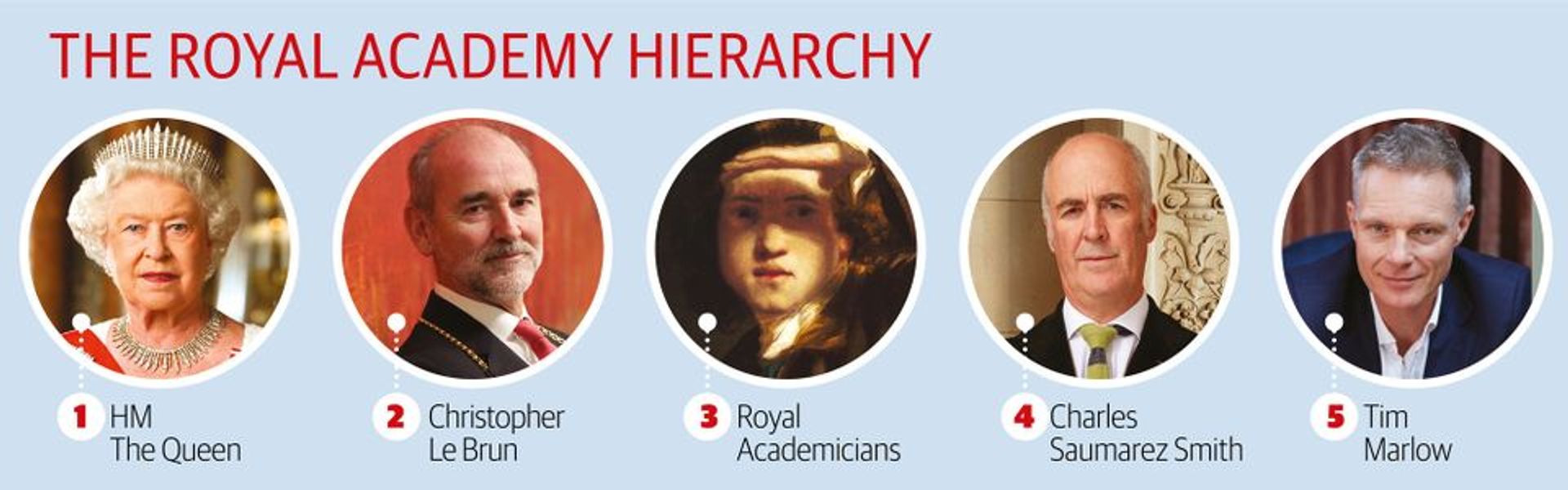

Charles Saumarez Smith’s place in the RA hierarchy may surprise some. The secretary and chief executive is fourth in the food chain: HM The Queen is top, followed by the president (Christopher Le Brun) and the Royal Academicians, then Saumarez Smith. “I’m subordinate to the Royal Academicians, so around 128th on their list,” he says. There are indeed 127 Royal Academicians in total: 80 aged under 75, and 47 over that age.

Saumarez Smith describes the RA as “rather like a Cambridge college, full of strong-minded individualists who own it. One of its strengths, though, is that it is very democratic and subject to constant organic change. Even in my time, there has been a generational shift; we’re now more broadly representative of the art world,” he says, pointing to changes on the RA Council, which now has external members representing the media, legal and finance matters.

The 250th anniversary redevelopment matters because “the project will make us look more like an academy and less like a kunsthalle”. He admits that, on joining the RA 11 years ago, he was only vaguely aware that an art school was at the heart of the institution.

Christopher Le Brun Benedict Johnson

2) President: Christopher Le Brun PRA

The painter Christopher Le Brun answers to The Queen in his role as the president of the Royal Academy, but he is essentially in charge. “The academy is led by the president on behalf of the Royal Academicians,” he says.

Le Brun, now in his seventh year as the RA’s supreme leader, is elected by secret ballot. “I wait alone until Charles [Saumarez Smith] comes to tell me the result,” he says. Under his tenure, he says that he has “got rid of much of the second-rate stuff”. Asked if he gets paid a substantial amount for working three days a week, he politely but firmly responds: “No”.

He says that the system of electing Royal Academicians is “only fit for purpose if the best artists and architects are elected”. Under the age-old system, once a name has been added to the current nominations book, signatures must then be elicited from eight other RAs in support of the nomination. (At this stage the nominee becomes a candidate.) The artists Jane and Louise Wilson became the second duo, and the first twins, to be jointly made a Royal Academician in April.

Rebecca Salter, the keeper of the Royal Academy Cat Garcia

3) Keeper’s House

“The problem with being called ‘the keeper’ is nobody knows what you do. Mostly people think of zoos!” says Rebecca Salter, who became the keeper of the Royal Academy last year. “My primary job is to steward the Royal Academy Schools”, alongside the head of the Schools, Eliza Bonham Carter, Salter says.

The Keeper’s House now contains the Friends’ Room, a restaurant and cocktail bar, with a light-filled studio for the keeper on the top floor. There is a back way to access the studio—the “model’s staircase”—which provides more privacy than the main access through Burlington House. “Historically, you were supposed to live onsite and make sure all the windows were closed at night,” she jokes. “And pay the wages.”

The Library at the Royal Academy of Arts Carolina-Faruola

4) Library and archive

“The archives at the academy are among the most important primary resources for the study of British art history anywhere,” says the RA’s archivist Mark Pomeroy. “We’ve got major holdings on Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, then going forward into the 19th century, William Blake Richmond and Thomas Lawrence,” he says.

Among the holdings are artefacts such as Reynolds’s sitters book, which is “a remarkable insight into one of the most successful portrait painters of all time”, Pomeroy says. But there are also more prosaic objects. “My absolute favourites are these little weekly shopping lists for the housekeeper from 1788,” Pomeroy says. “There was beer and rum, and it turns out these are the expenses for the life school.”

One of the most important objects in the archive is the “roll of obligation”, a large sheet of velum that has been signed by every member of the academy since its inception in 1768, from “Joshua Reynolds right up to Isaac Julien”, Pomeroy says. “It’s a 250-year-old active document,” headed by the obligation which, he says, essentially declares: “‘I am now signed up and part of the gang’.”

5) Friends of the RA

The scheme, the first of its kind in the UK, celebrates its 40th anniversary this year. It was set up by the former RA President Hugh Casson when “he realised early on that, because we don’t have a government grant, we needed a different way of funding ourselves”, says Charlotte Appleyard, the director of development. There are just under 100,000 Friends of the RA and they usually make up around “50% of our audience for each exhibition”, Appleyard says.

Tim Marlow, the RA’s artistic director Cat Garcia

6a) The Sackler Wing of Galleries, 6b) Main Galleries, 6c) Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries

The RA’s programme will now stretch across three suites of galleries, and is led by Tim Marlow, the RA’s artistic director. He says that the management “took a long, hard look” at the staffing structure when he was appointed in 2014. “They decided to bring content under one person so I’m responsible for exhibitions, publications, learning [other than the RA Schools], the library and research. I can’t cherry-pick and curate shows but I can co-curate every so often.”

But is his power unlimited? “There are various committees overseeing my role so I’m not given a blank canvas; they’re the moral conscience of the RA,” he adds. These include the exhibitions committee and the council made up of rotating members, which is chaired by the president. Is this structure rather stifling? “There are instances at other institutions where trustee boards are involved in programming; it’s much less insidious than that.”

Marlow is rejuvenating the exhibition programme by mounting blockbuster shows dedicated to living artists such as Ai Weiwei in 2015 and the forthcoming Marina Abramovic exhibition, scheduled for 2020. “I’ve made no secret of the fact that we should broaden our audience by showing contemporary art but reassessing art history is just as exciting and important,” he says, pointing to the forthcoming Oceania show (29 September-10 December).

Eliza Bonham Carter, the head of the RA Schools Cat Garcia

7) RA Schools

The RA’s keeper, Rebecca Salter, estimates that “99% of people would have no idea” that there is an art school at the Royal Academy. “In the very early days [the academicians] were quite clear they wanted it to be different from the European academy model; they wanted instead for there to be a multiplicity of voices teaching the students,” Salter says. “That has become what is considered the standard British art school model.”

The RA Schools offer the only three-year postgraduate fine art course in the UK, which is free. There are around 17 students in each year, creating a close-knit atmosphere, according to the head of the RA Schools, Eliza Bonham Carter. “One of the things we try and ensure is that we find as many different ways of talking about art as we can, from very formal academic structures like a lecture or an artist’s talk to group critiques and one-to-one tutorials,” she says. “But we also have lunch together every day, so lots of different conversations happen there. And then in the evening there is the students’ bar,” which, she adds, is “the best bar in Mayfair”.

With the new link between the RA’s buildings, visitors will walk past the Weston Gallery, a new project space for the work of students and alumni, and the Schools’ famous corridor filled with casts, traditionally used for drawing instruction. Students continue to work with the casts today. “I have to say, whenever I see an Eddie Peake performance”—Peake often uses naked or semi-naked performers in his works—“I can’t help think about the cast corridor,” Bonham Carter says.

8) Art handlers

There should be an element of “invisibility” about the work carried out by art handlers, says Simon Streather, who has been at the RA for 11 years. “Usually when things are quiet, we are at our busiest, with shows coming down or being put up,” he says. “It can be quite an unusual job,” Streather says. “We can be moving 97 tons of rebar steel for the Ai Weiwei exhibition and then using sugar tongs to move little glass balls in the Joseph Cornell show.”

The art handlers inhabit the belly of the beast, tucked away in the vaults beneath the main galleries, where works can come in through the back entrance and be taken up into the galleries using a hefty goods lift, which has been moved and replaced as part of the big revamp. Its former place has been taken, fittingly, by a statue of Hercules, which the public will be able to see when walking along the new link between the buildings.

9) The cast corridor

Numerous plaster casts have been part of the Royal Academy Schools and collection since its earliest days. But none is more macabre than Thomas Banks’s Anatomical Crucifixion (James Legg) from 1801. Before 1832, only the bodies of executed criminals could be used for dissection. Legg was a retired army captain at the Royal Hospital Chelsea who had murdered another Chelsea Pensioner after challenging him to a duel, for which he was hanged. His body was taken straight from the gallows and nailed to a cross. It was done to settle a debate about the anatomy of crucified bodies, at the behest of the Royal Academicians Banks, Benjamin West and Richard Cosway.

10) Red collars

If you need anything doing on the premises of the Royal Academy, you are likely to have to go through a red collar. They are the “custodians of the keys”, says the red collar Steve Rampasard. Recognisable by their distinctive dark suits with scarlet collars, which until recently were made for each member of the team by a Savile Row tailor, their roles span from being front-of-house duty manager to announcing the presence of royalty at major events and serving the traditional beef tea and dry biscuits to academicians on the Summer Exhibition judging days.

They are on site “24/7, 365 days a year”, Rampasard says, and must have good relationships with all staff and academicians. Rampasard names some of his favourite RAs (including the two most recent keepers, Eileen Cooper and Rebecca Salter) and the close relationship that the red collars have with these world-famous artists, from turning a blind eye to David Hockney smoking in the Academicians’ Room—“he shouldn’t have”—to Anish Kapoor mailing Rampasard a signed copy of his book after he had joked about never getting an autograph.

Who's the boss? The Royal Academy hierarchy Queen: Julian Calder for Governor-General of New Zealand. Le Brun, Tim Marlow: Cat Garcia. Reynolds: National Portrait Gallery. Saumarez Smith: Benedict Johnson