“I never thought I’d be doing ecological art at age 56,” says the Canadian novelist and artist Douglas Coupland of his installation Vortex, a year-long installation opening at the Vancouver Aquarium on 18 May (until 30 April 2018) that looks critically at the effects of plastic waste in oceans. “But it just came to me,” he adds—and it turns out he means that literally.

Coupland had the idea for Vortex in 2013, while walking along the beach in Haida Gwaii, the archipelago off Canada’s northwest coast previously known as the Queen Charlotte Islands. With its temperate rainforests and teeming wildlife, Coupland considers Haida Gwaii as “the most alive place per square footage in the world” where you can “feel one” with creation. So it struck him when he found, washed up on the shore in such a pristine location, a pink plastic Japanese shampoo bottle.

The installation, which Coupland gave us a tour of in progress last month, includes hundreds of such objects, gathered by the artist and other volunteers around British Columbia, working with the non-profit organisation Ocean Wise. It is named after the Pacific Trash Vortex or Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a swirling accumulation of debris, chemical sludge, nylon netting and particles collected by the ocean’s currents.

The work’s central feature is a battered fiberglass Japanese fishing boat that also washed up on the shores of Haida Gwaii, six years after the 2011 tsunami off the Tōhoku penninsula. Sitting in a pool filled with water, the boat is occupied by a plastic figure of Andy Warhol and another of a Sudanese migrant woman holding a Nestle water bottle, linking the 1960s, when plastic was seen as the ideal futuristic material, with the present, when the ubiquitous stuff has run amok. “I began working with plastic thinking it was eternal and shiny and happy,” Coupland says in a video about the project, “and the punchline is that plastics are a mess.”

Inspired by both Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa and Bill Reid’s bronze sculpture The Spirit of Haida Gwaii, the installation also includes two childish bobblehead figures clutching iphones and plastic bags, flanked by taxidermied wildfowl. Screens surrounding the pool project images of Haida Gwaii and speakers emit the islands’ natural sounds, while a tank full of jellyfish and plastic debris and a submerged city/reef made of Lego riffs on the idea of real versus fake landscapes.

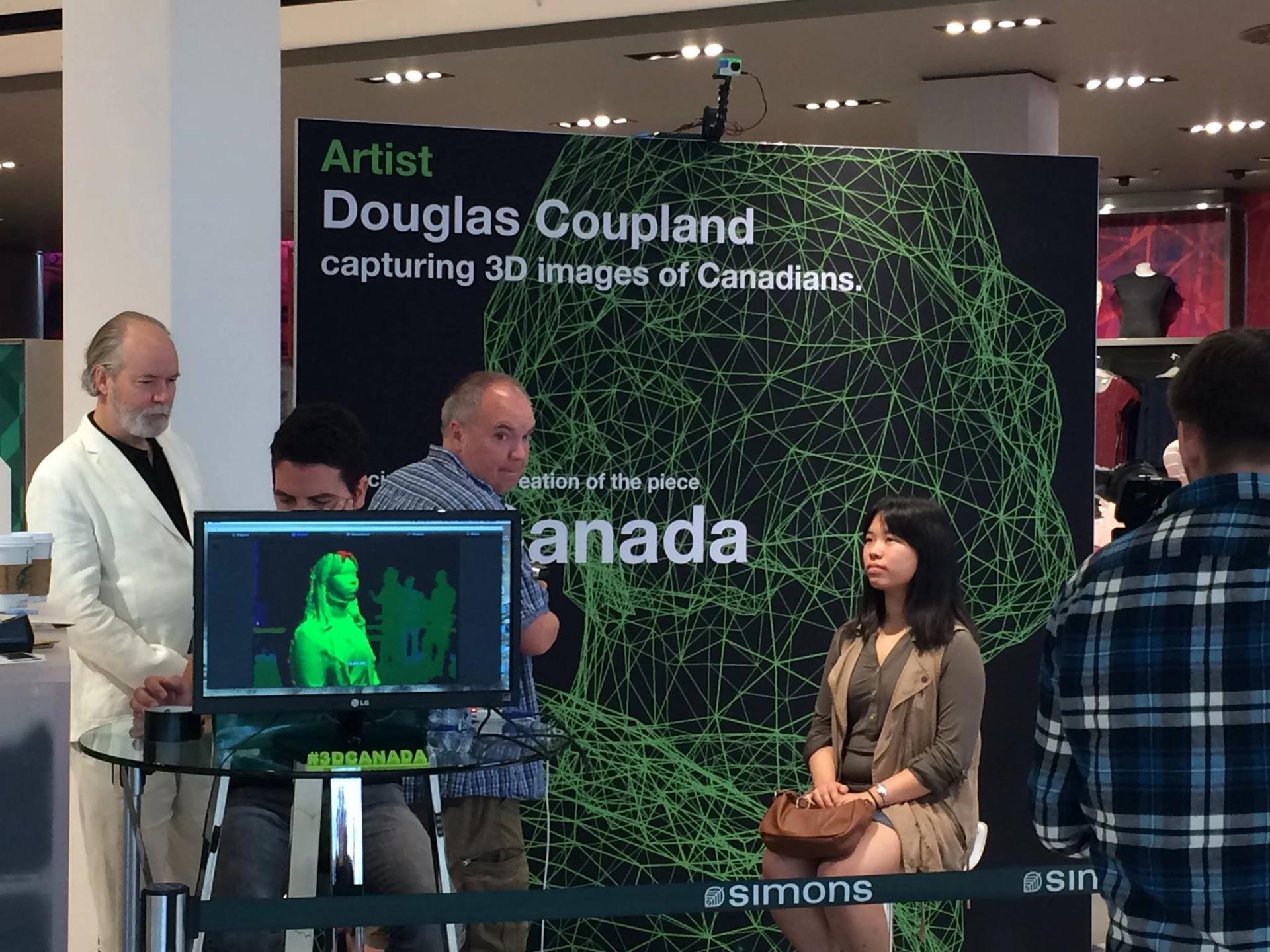

Coupland finds a more positive use for plastic in another work, The National Portrait, one of his most ambitious projects that has been two year’s in the making, which opens at the Ottawa Art Gallery on 29 June. Working with the shopping mall company Simons, Coupland has created more than 1,200 3D-printed sculptures made from bio-degradable plastic, depicting a cross-section of Canadians. His sitters included a Cree Indian chief in full head-dress, an entire family of turban wearing Sikhs and a gamut of men, women and children.

Douglas Coupland scans Canadians' faces at the West Edmonton Mall

To gather the images for the massive group portait, Coupland set up pop-up labs in Simons stores around the country where people would have their heads scanned and receive their own miniature version of the kind of object once reserved for emperors and kings. The innovation of 3D-printing “allows you for the first time in history to be promiscuous with the bust,” Coupland says.

The project exploits what Coupland calls the “crisis of representation” presented by the new technology and the malleability of plastic, to offer fiercely individualistic portraits that celebrate a diverse Canadian mosaic.

Both shows represent what the artist calls a “full circle” return to his first forays into plastic art making before he began his career as a writer. “But now, I have a more conscious grasp of what I was doing then,” he says. “I’m interested in the toxicity that lies beneath the pretty pink plastic.”