Fashion has always drawn inspiration from many sources, including things we can see every day, such as the natural world and paintings, but also from more remote fields, such as the exotic and technological. Even the esoteric realm of religion—and Catholicism in particular—has long influenced designers. Dolce & Gabbana created a line of clothing based on the mosaics in Monreale Cathedral, near Palermo, Sicily, where Domenico Dolce was born, and Cristóbal Balenciaga made garments and evening capes similar in style to clerical copes, informed by his own Spanish Catholicism. These designs will soon go on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the Costume Institute spring blockbuster show Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination (10 May-8 October).

“Some might consider fashion to be an unfitting or unseemly medium by which to engage with ideas about the sacred or the divine. But dress is central to any discussion about religion – it affirms religious allegiances and, by extension, it asserts religious differences,” says Andrew Bolton, the exhibition’s curator and head of the Costume Institute. “While religious dress and fashion are two distinct entities governed by different systems of knowledge, both operate as a visual language, relying on subtle visual codes to perform specific functions and to express complex ideas about identity. In the Catholic Church, dress not only distinguishes hierarchies but also gender distinctions in much the same way as it does in society in general.”

From left: Donatella Versace, Anna Wintour, Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, Christine Schwarzman, Stephen A. Schwarzman, Carrie Rebora Barratt, and Andrew Bolton at The Met’s Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination press preview in Rome Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art/@sgpitalia

It is a fitting theme, then, for the show tied to the annual Met Gala, the museum’s most star-studded fundraising event, which this year is co-chaired by Amal Clooney, the human rights lawyer (and wife of movie star George Clooney), the singer Rihanna, the designer Donatella Versace and Vogue’s editor-in-chief, Anna Wintour, along with the philanthropist Stephen Schwarzman and his wife, Christine. A preview of the exhibition presented at the Colonna Gallery in Rome on 26 February was attended by Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, the president of the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Culture, who wore red and black de rigueur, with Anna Wintour dressed in matching colours. “You are what you wear,” Ravasi declared at the press launch. Dress, he explained, defines the man, and God appears in the Bible as a creator but also as a tailor: “The Lord God made tunics of skin for the man and his wife, and he dressed them” (Genesis, 3:21).

The show also comes at a special time for the Roman Church; not only do many non-Catholics see Pope Francis as a charismatic figure, but Catholic aesthetics are at the centre of the recent television success The Young Pope, starring Jude Law. Perhaps that is why the church has been so generous, lending around 40 masterpieces from the Sistine Chapel’s sacristy. Many of these objects, including 12 vestments commissioned by Empress Maria Anna Carolina of Austria for Pope Pius IX, are leaving the Holy See for the first time. Some last left their papal fortress in 1983 for The Vatican Collections, the third most visited exhibition in the Met’s history. The collection includes liturgical garments and accessories, such as tiaras and rings—one, donated by Isabella II of Spain to Pope Pius IX, is adorned with 18,000 diamonds—from the 18th to the 21st century, covering 15 papacies. The oldest work is a mantle worn by Pope Benedict XIV (1740-58), the most recent a pair of red shoes that belonged to Pope John Paul II (1978-2005).

There are also more than 150 fashion items, mainly for women, that date from the beginning of the 20th century up to today. These will be displayed together with work from the Met’s Medieval collection, selected by Griffith Mann, the curator in charge of the department, in the Byzantine and Medieval art galleries and Robert Lehman Wing of the museum’s Fifth Avenue building as well as in the Met Cloisters farther uptown.

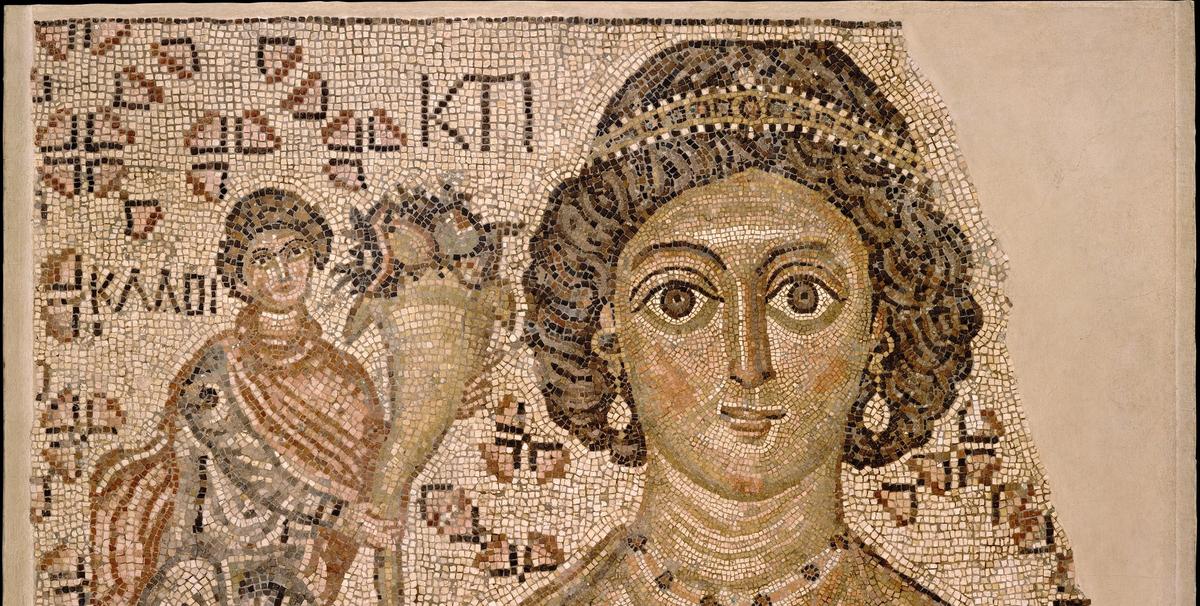

The exhibition starts in the Byzantine galleries, with garments inspired by that period’s architecture and religious art. Two dresses by Gianni Versace, created for his 1991 and 1997 autumn fashion shows and based on the micro mosaics of Ravenna’s Basilica of San Vitale, are displayed next to fragments of ancient mosaics and a silver-gilt processional cross dating from AD1000. The exhibition continues in the Medieval galleries, which, in contrast, focus on objects influenced by the Catholic hierarchy. Among the items included in this section is a Valentino piece that cannot be missed, designed by Pierpaolo Piccioli for the 2017 haute couture collection, which pays homage to the “great cape” worn by cardinals on the church’s most solemn liturgical occasions. There is also a chasuble designed by Jean-Charles de Castelbajac for Pope John Paul II, which he wore on World Youth Day in 1997.

Farther on, visitors can admire garments that draw on the habits of Catholic sisters and nuns, and others from the Cult of the Virgin Mary. Among these is one created by Yves Saint Laurent for the statue of the Virgin of El Rocío in the Church of Our Lady of Compassion in Paris, and another by Riccardo Tisci, Givenchy’s former creative director, for Our Lady of Graces in the Parish of Saint Peter the Apostle in Palagianello, in southeastern Italy. In the Robert Lehman Wing, the objects draw on the cult of the saints and angels, including a garment by Elsa Schiaparelli embroidered with the Keys of Heaven (the designer was baptised in St Peter’s Basilica in Rome), and another with enormous wings, called Angel of Gold, by Roberto Capucci.

The fashion pilgrimage ends at the Met Cloisters, which was built using original materials from historic French monasteries and abbeys. Consequently, it provides the perfect setting for pieces based on the costumes of the religious orders, including Balenciaga’s single-seam bridal gown from 1967, with its flying-nun-like headpiece.

Throughout the exhibition, materials, colours, shapes and genres are mixed and matched, with masterpieces of ancient art displayed next to modern clothing. But the installation also draws clear correlations between the pageantry of the church and the runway. “Beyond semiotics, religious dress and fashion… are both inherently performative,” Andrew Bolton explains. “There are distinct parallels between a fashion show and a church procession. Typically, both follow an orderly and regulated arrangement; both involve active and passive participants; and both are accompanied by music.”

According to Ravasi, clothing has a material and physical side, but also a symbolic significance. The cardinal identifies four aspects of this: moral, social, cultural and sacred. “All regions have their own vestments and ornaments that typify religious ceremonies,” Ravasi said at the preview in Rome. “These garments are not necessary in themselves, because underneath them we wear secular clothes. They are ornamental and rich because they represent the transcendental, the dimension of religious mystery.”

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Digital

Gianni Versace, evening dress, autumn/winter 1997-98 haute couture

“Gianni Versace’s use of religious imagery highlighted its ubiquity in popular culture, especially the cross, a defining decorative element of Versace’s final collection,” the exhibition catalogue states, including a series of garments made from a specially developed metal-mesh “that draped and clung to the figure like bias-cut silk but also resembled mail”. One example is a gold evening dress bisected from neck to hem by a large cross, based on a Byzantine gilt-silver processional cross from the Met’s collection.

Courtesy of the Collection of the Office of Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff, Papal Sacristy, Vatican City

Mitre of Pius XI, 1929

Clearly drawing on Fascist imagery, this white silk satin mitre was a gift from Italy’s then prime minister Benito Mussolini to commemorate the signing of the Lateran Treaty on 11 February 1929, in which the Italian government officially recognised Vatican City as an independent state and compensated the church for the loss of the Papal States. The diplomatic reconciliation would be short-lived, however, as Pope Pius XI became more critical of Mussolini’s totalitarianism, denouncing the Fascist regime as one that “snatches the young from the Church and from Jesus Christ, and which inculcates in its own young people hatred, violence and irreverence”.

Courtesy of Dolce & Gabbana

Dolce & Gabbana, evening dress, autumn/winter 2013-14

In a recent collection, Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana “drew on the dazzling mosaics of the Cathedral of Monreale in Sicily”, a location with a long history for the designers, since Dolce was born and raised on the Italian island. The church’s tiled icons were meticulously recreated in printed silk jacquard, gold embroidery and crystals in a number of garments, including this modest but lavish dress, which features an image of the “the famously beautiful Saint Agatha of Sicily, a highly venerated virgin martyr”.

Courtesy of the Collection of the Office of Liturgical Celebrations of the Supreme Pontiff, Papal Sacristy, Vatican City

Red leather shoes of John Paul II, made by Loredano Apolloni, around 2000-05

The tradition of red papal shoes is centuries old, the colour signifying “the blood of Christ’s Passion and of Catholic martyrs, as well as the fire of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, which marks the birth of the church”, according to the catalogue. The fancy footwear only became a regular choice with Pope John XXIII (1958-63) and the loafer style was adopted by Paul VI (1963-78). John Paul II (1978-2005) favoured more of a mahogany later in life, like these slippers worn by the Polish pope at the end of his pontificate, similar to the ones he was buried in. But the tradition may have ended with Benedict XVI (2005-13), whose ruby red shoes led Newsweek to declare: “The Pope Wears Prada”. (For the record, they were by the Italian cobbler Adriano Stefanelli.) When he took up the papacy in 2013, Francis chose to eschew the red shoes for a more humble plain black pair.

Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Digital Composite Scan: Katerina Jebb.

Dalmatic (front) of Pius IX, 1845-61

The Empress Maria Anna Carolina of Austria commissioned a suite of 12 vestments for Pope Pius IX that drew on copies of well-known religious paintings by Italian artists, including Raphael, Paolo Moranda Cavazzola, Paolo Veronese, and Alessandro Turchi. The wardrobe “narrates the trajectory of human existence, from the Fall in the Garden of Eden to redemption through the Passion of Jesus Christ”, the catalogue states. It took 15 women from Verona’s Istituto Femminile di Don Nicola Mazza—where the students’ “meticulous rendering of figures’ faces and costumes was a specialty”—almost 16 years to complete the suite.