Basic human irritants too often prove the dominant theme of an art fair, no matter how apparently high-minded the clientele. And so, entering Tefaf New York Spring’s preview day on Thursday (3 May) much talk was devoted to the stifling heat of the previous day’s preview of Frieze New York in its tent on Randall’s Island. Tefaf, sheltered from New York’s spring heatwave in the relative cool of the Park Avenue Armory, was, as one dealer quipped, “at least humane”.

Tulips, oyster shuckers and general slickness aside, the second edition of Tefaf New York Spring does not feel much like the Maastricht original: this is a very different crowd. But, it is good, very good, and, like festival-goers discovering glamping for the first time, big Modern and contemporary art galleries taking part for the first time appear won over, and not simply by the air conditioning.

Many dealers used to the capacious stands of Art Basel and Frieze find themselves in far smaller spaces at Tefaf. However, Brett Gorvy of Lévy Gorvy says: “The booths here are more intimate, like cabinets of curiosity.” He added: “It’s a very cosmopolitan fair; the top 100 collectors in the US are probably here right now. People are coming in and making decisions very quickly.” A couple of hours into Thursday’s preview, Lévy Gorvy had sold Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Extra Cigarette (1982) with an asking price of $5m, Andy Warhol’s Brillo Soap Pads Box (1964/1969) which went immediately with an asking price $950,000, and, according to Gorvy, there are “four people lining up” for a 1970s untitled oil by Willem de Kooning, priced at $1.35m. “I think today, you define yourself by the fairs you chose to do,” he added. “We stopped doing Frieze New York and now do Frieze Masters in London and Tefaf New York.”

By the end of Thursday, Lisson Gallery had also nearly sold out its booth, with sales including an early ceramic work by Mary Corse (asking price $450,000), Estructura by Carmen Herrera ($450,000), a piece by Lee Ufan ($450,000), and a work on paper by Sol LeWitt ($140,000).

The trend for themed booths is strong: Dickinson from London chose the Modern Muse, Ekyn Maclean (New York and London) have gone for international Pop, Beck & Eggeling hone in on the Zero group, Helly Nahmad concentrate on works from the 1920s and Galerie Gmurzynska go full on Bond villain’s layer with a stand designed by the creative director Robin Scott-Lawson containing works by Yves Klein, Joan Miró, Roberto Matta and Wifredo Lam.

Here are a few things at the fair that caught our eye:

Philip Guston, Forms on Rock Ledge (1979) The Estate of Philip Guston Courtesy the Estate and Hauser & Wirth Photo: Genevieve Hanson

Philip Guston, Forms on Rock Ledge (1979), at Hauser & Wirth

“It’s a play on painterly sculpture and sculptural painting. When you look at Philip Guston’s work, it is sculptural, and when you look at Eva Hesse’s sculpture, they have this painterly quality to them. In fact she always had a dream of being a painter,” says Marc Payot of Hauser & Wirth of the gallery’s presentation at Tefaf of Hesse, Guston and Louise Bourgeois together. This Guston painting, finished the year before the artist died, “combines all the visual elements that were important in his work: the horizon line, the shield, the canvas with nails hammered into it, and the bodily forms,” Payot says. “Then there is the blue background, a colour which is more commonly seen in his abstract works of the 1950s and 60s”. The painting sold on preview day for $5.5m.

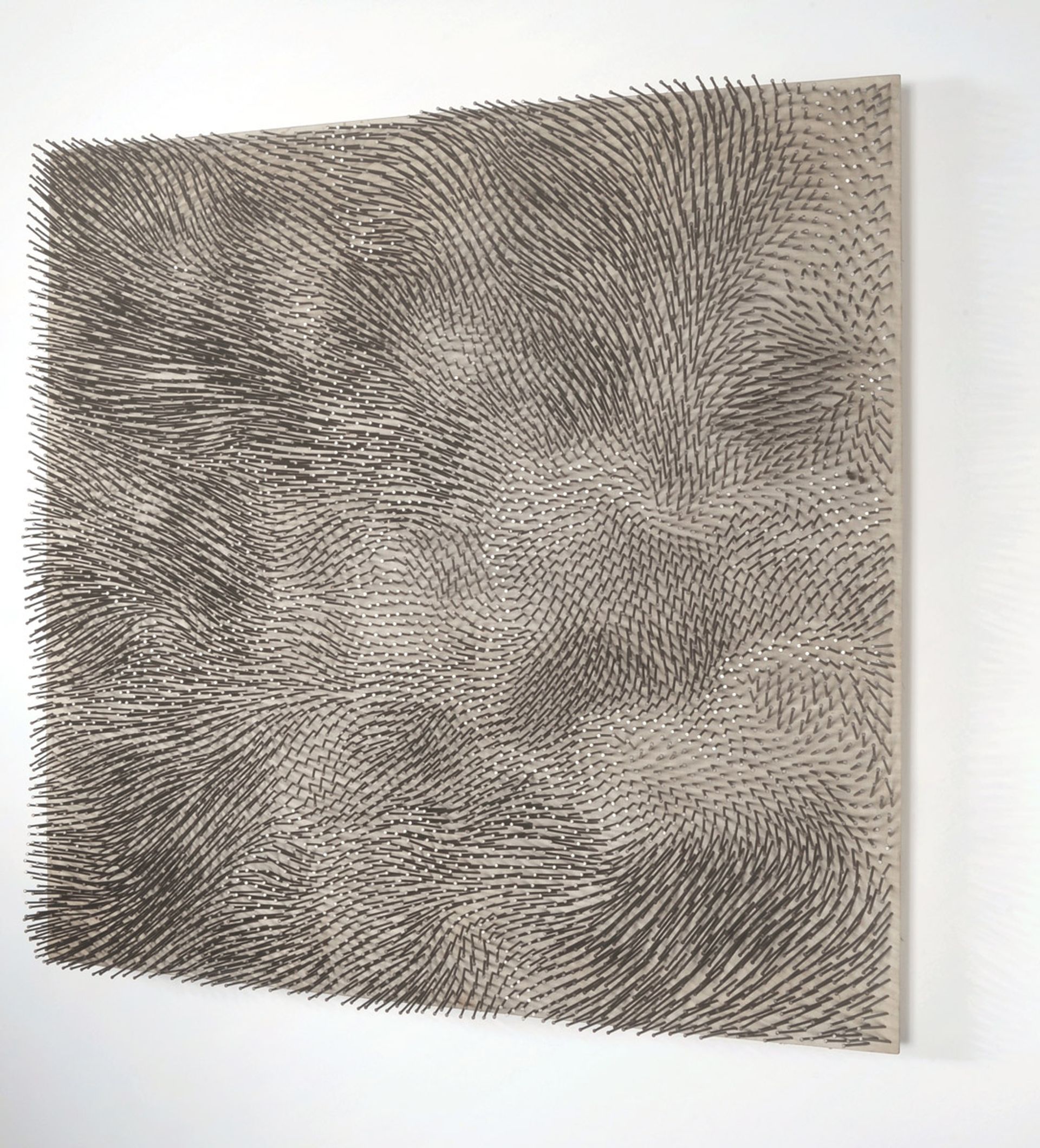

Gunther Uecker, Strömung, 1972 Beck & Eggeling

Gunther Uecker, Strömung (1972), at Beck & Eggeling

The Düsseldorf-based gallery Beck & Eggeling devoted its room upstairs in the Park Avenue Armory to a display of post-war Zero group works by Heinz Mack, Otto Piene and Günther Uecker. Two of Uecker's nail works shown have been in German private collections since they were bought from the artist, in 1964 and 1972 respectively. Centre stage is a large work, Strömung (1972). “It was shown at the Guggenheim in New York in 1972, and then returned to a collector’s home near Düsseldorf until now,” the dealer Michael Beck says. “I have been trying to persuade them to sell it for four or five years. This is the first time it has been shown in public, and the first time it has returned to New York.” Most desirable in Uecker’s work, Beck says, “is a feel of movement in the nails, like wind blowing through a field, as in this work.” The piece has an asking price of €2.2m.

Alexander Calder, Dancers and Sphere (1938) Galerie Natalie Seroussi

Alexander Calder, Dancers and Sphere (1938), at Galerie Natalie Seroussi

Although Calder is more closely associated with the circus, the artist also maintained a love for ballet and theatre throughout his life, and even designed the sets for Erik Satie’s Socrate in 1936. He created this mobile “ballet-object” as a maquette for a sculptural commission by the power company ConEd for its pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair exposition in New York. Ultimately unrealised, the figures in this piece later provided inspiration for The Four Elements (1961), a monumental sculpture for Stockholm’s Moderna Museet. “As Calder created Dancers and Sphere for the New York Fair in 1939, we thought that it was a nice return to bring back the work to the United States 80 years later for a similar occasion”, says Julien Seroussi, the gallery director. This whimsical work was previously in the collection of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé.

David Adamo Untitled (eggs 4) (2017) Peter Freeman, Inc.

David Adamo, Untitled (eggs 4) (2017), at Peter Freeman, Inc.

As part of a presentation of four centuries of trompe l’oeil works—right down to a faux-wooden floor for the booth—Peter Freeman has selected pieces ranging from a 18th-century Italian landscape by Bartolomeo Sampellegrini da Pizacenza to a cast-bronze cardboard wine box by Rachel Whiteread. Among the most recent are David Adamo’s pink glazed bronze doughnut and an acrylic and enamel painting on canvas, apparently with eggs plastered across its surface. “Artists have been working with trompe l’oeil throughout the history of art, and we thought it would be fascinating to bring multiple time periods and generations together for this presentation, and Tefaf New York is the perfect place to do it”, says Jayne Johnson, a gallery director. The group also includes paintings by John Frederick Peto and De Scott Evans, as “the 19th century was an especially interesting moment in which trompe l'oeil took on a distinct ‘American-ness’” Johnson says. This trend continued through to Pop art, as with Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes and an unusually conceptual Roy Lichtenstein, Things on a Wall (1973). Today, Johnson says, “contemporary artists, like Charles LeDray and David Adamo, [continue to] push the idea into new directions”.