After multiple documentaries about Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-89), there is finally a narrative film on the brash photographer who didn’t blink in his erotic black and white images of black and white men. The feature, starring the British actor Matt Smith (known for his roles on Dr Who and The Crown), premiered last week at the Tribeca Film Festival.

Mapplethorpe became the anti-Christ in the US culture wars of the late 1980s and early 90s. His name was synonymous with what the conservative Right found objectionable in contemporary art. A museum director who programmed a Mapplethorpe retrospective in 1990 was arrested, prosecuted, and eventually acquitted.

Yet the film-maker Ondi Timoner’s bio-pic, Mapplethorpe, supported by the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, focuses on the man rather than on his legacy. There’s still plenty of sturm und drang, and the man who was a hero for his views on freedom of expression emerges as ruthlessly and recklessly ambitious.

Smith portrays Mapplethorpe as a determined young rebel, browbeaten by his Catholic father, who finds an early friend and artistic companion in the musician Patti Smith, played by the up and coming actress Marianne Rendón. As Mapplethorpe becomes increasingly drawn to other men, Smith decamps from their dingy Chelsea Hotel room.

The photographer then meets the urbane collector and aesthete Sam Wagstaff, played by the film and theatre actor John Benjamin Hickey, who clears the path for his work to be shown in galleries that spurned him before. The brazen pictures and images of flowers make Mapplethorpe rich—as HIV ravages his models, his friends and eventually the artist himself. “Your pictures are quickly becoming a gallery of the dead,” says Wagstaff, who also died from Aids.

Filmed in offices, galleries and bedrooms, the feature presents the successful Mapplethorpe as a nasty cocaine addict who torments his assistant, his younger brother Edward, who is also a photographer. The jealous Robert even forces Edward change his professional name to Maxey. The audience that would mourn the condemnation of the photographer’s work at the time might not mourn him after seeing the film.

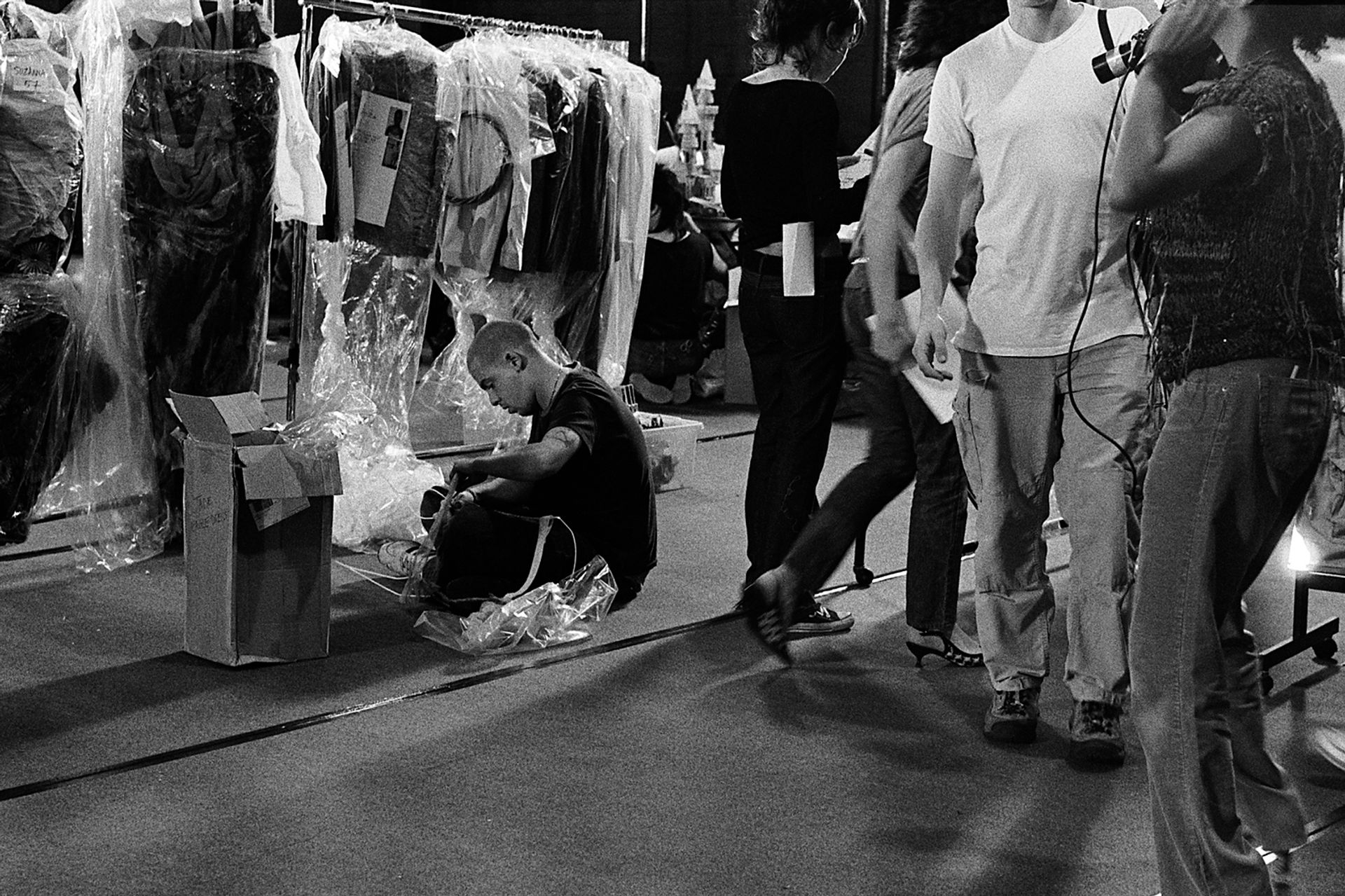

A still from Ondi Timoner’s bio-pic Mapplethorpe

Timoner spent 12 years on the project. Her script is based on an earlier screenplay by Bruce Goodrich adapted from the 1995 biography of Mapplethorpe by Patricia Morrisroe, who was chosen by the photographer to write his life story.

Patti Smith (the subject of her own bio-pic at Tribeca), did not cooperate with the project, and her writings, recollections and music are a major absence in the drama. So is the lack of Mapplethorpe’s self-portraits, which track the young man’s rise and were a continued feature of his work, through to his death, aged 42. Timoner may have left the self-portraits out to avoid confusing Mapplethorpe’s image with Matt Smith’s portrayal, but those pictures are the closest thing to a biographical trail in his work.

Mapplethorpe the drama does not lack male genitalia, which may attract the titillated but still risks shortening the film's reach in the marketplace. The bio-pic's real challenge in drawing more than its natural audience is to convince a younger public that a man who died 30 years ago still embodies dreams of freedom and creativity.

Also screened at the Tribeca Film Festival

The Man Who Stole Banksy by Marco Proserpio

In The Man Who Stole Banksy by Marco Proserpio, we travel to the Israeli-occupied West Bank, where Banksy painted the wall separating Israel and Palestine in 2007, and decorated facades of buildings in Bethlehem.

When a local businessman removes a painting from a wall and sells it, the tour of yet another Banksy paint-by shifts into a debate over the ownership of art. Graffiti artists often call it theft when work that they painted is turned into cash on the market. Some artists have responded by painting over their public work before anyone can monetise it—destruction as preservation of the original intent.

Is obliterating a work of art a legitimate response to the threat of having that street work removed and sold in the name of art history? The issue, considered here in Palestine and Italy, is now in the courts in the US.

The Proposal by Jill Magid Photo: Jarred Alterman

The question of ownership and control arises again in The Proposal, in which Jill Magid, the filmmaker (who began this project as part of an exhibition), examines barriers to studying the archive of the Mexican architect Luis Barragan (1902-88). The rights to the architect’s archive are owned and controlled by a foundation created by the Vitra Corporation in Switzerland, and administered by the wife of the firm’s CEO, who received the archive as an engagement present.

Magid takes us back to the transfer of the rights, and initiates a correspondence with the woman, Federica Zanco, who keeps scholars and everyone else away. The proposal in the title refers to Magid’s offer to exchange a ring with a diamond, synthesized from Barragan’s cremated remains (we see them exhumed onscreen), in exchange for returning the archive to Mexico—a romantic conceptual gesture. That overture did not make the two parties any closer, but the film (along with a previous New Yorker article) reopens the dispute.

McQueen, directed by Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui Photo: Ann Ray

And McQueen, directed by Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui, surveys the career of the designer Alexander McQueen, who brought a rousing imagination to fashion for two decades until his death by suicide in 2010.

Given the public’s response to museum exhibitions devoted to McQueen (661,000 visitors went to the Met’s Savage Beauty tribute in 2011), a documentary about him can expect crowds worldwide. In this one, we get the trajectory of McQueen’s life from his humble beginnings in Stratford (where friends and family call him Lee) to directing Givenchy while starting his own fashion house, and a desperate stress-driven spiral into loneliness that ended when he took his own life after the death of his mother.

The runway scenes can be magnificent, as can the glimpses into men’s suit-making, where the gifted designer got his start in London. But much of the footage (besides recent interviews) looks like old VHS, which does not come to life on the big screen. Also, talk of McQueen’s reputed wit and bawdiness comes from others, and not from rare videotape of him. Nevertheless, given its subject, this documentary will travel.