There are not many dealers like Hudson. The much-loved single-named maverick was known for his ability to spot and nurture talent before the rest of the art world caught on. And Feature Inc, the gallery he founded and ran, first in Chicago and then in New York, up until his death in 2014, aged 63, became known as a space where artists who are well established today, like Richard Prince, Charles Ray and Huma Bhabha, had some of their first shows. “All around the country—all over the world—there were pockets of interesting things that I wanted people to enjoy, or at least be aware of,” Hudson said in 2010. “It seemed more important to stay open to the breadth of contemporary art than to settle on the obvious.” Perhaps this keen-eyed interest came from the fact that he was a performance artist and dancer himself. “He approached the gallery as if it was a work of art, and when you came in, it felt different,” says Matthew Higgs, the director and chief curator of New York’s White Columns gallery.

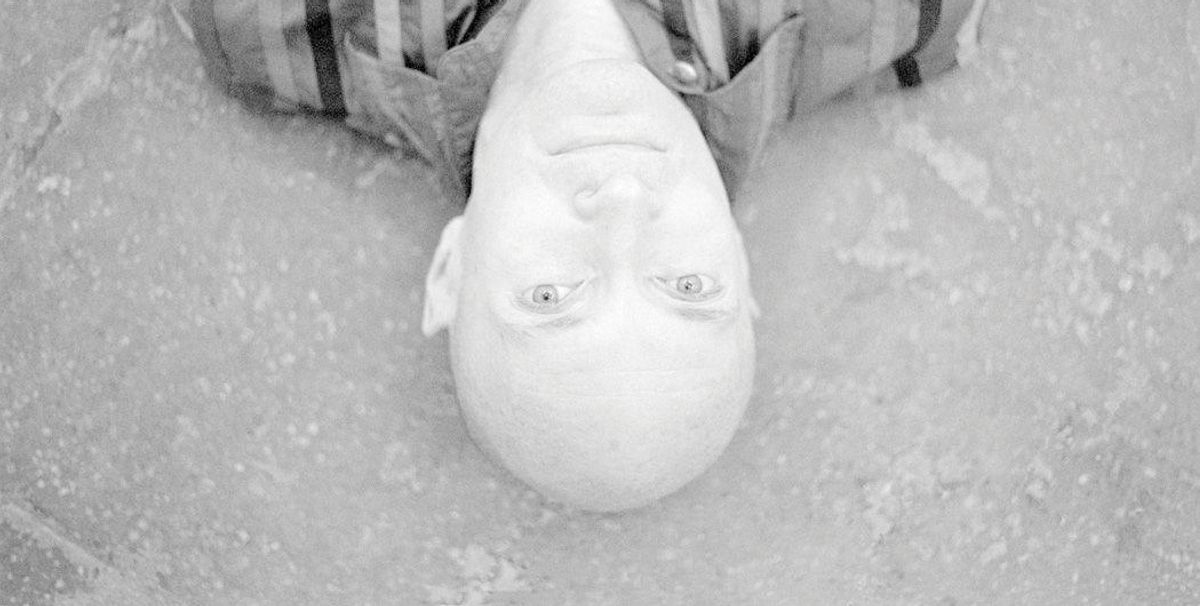

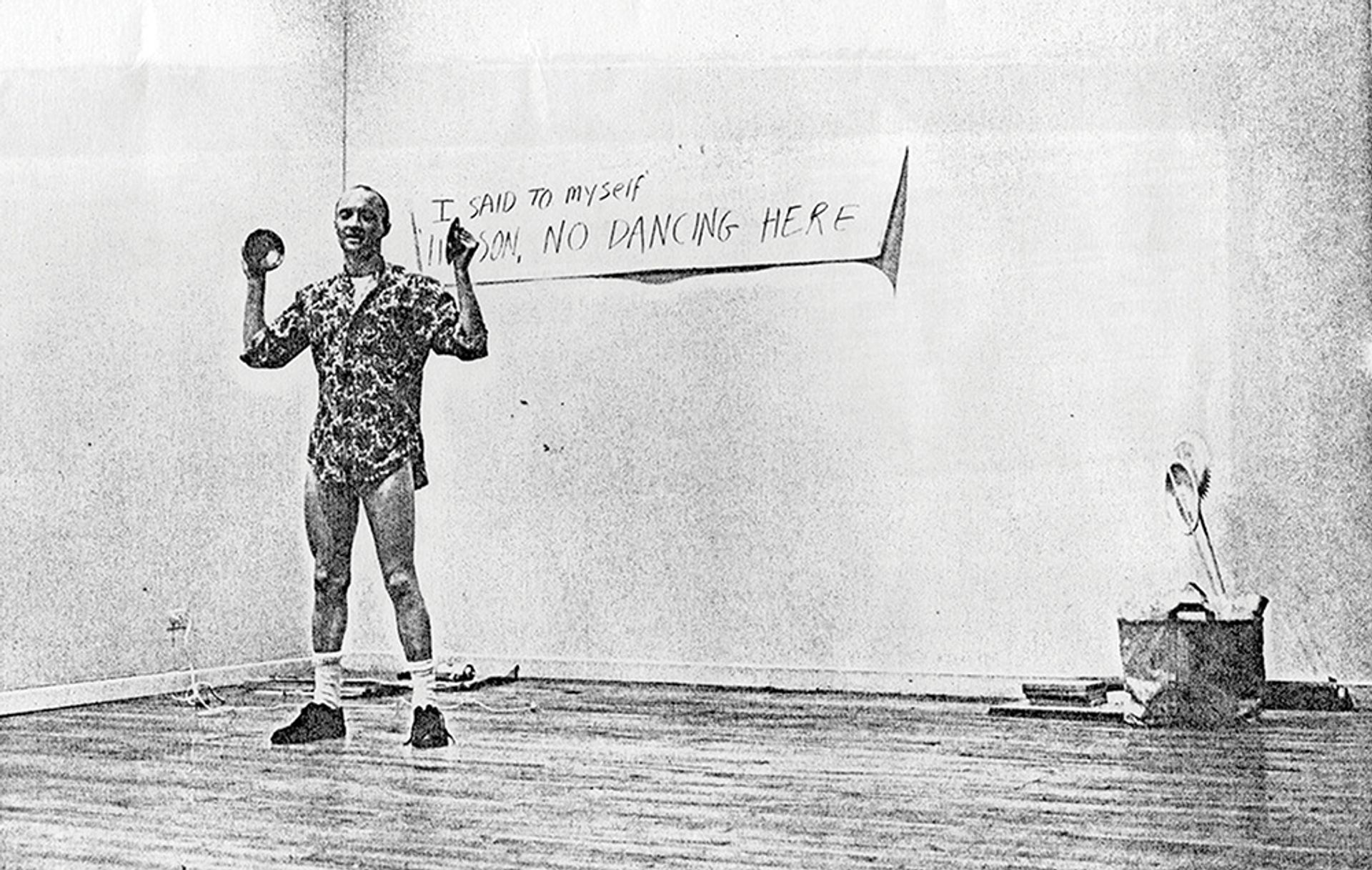

Hudson began his career as a performance artist and ran live events at the non-profit alternative space Randolph Street Gallery in Chicago courtesy of Feature Hudson Foundation

Higgs has organised a special section at Frieze New York dedicated to the dealer, who he says helped shape the contemporary art scene. For Your Infotainment includes displays focusing on eight artists whose careers were launched at Feature Inc—Dike Blair, Tom of Finland, Tom Friedman, Andrew Masullo, Takashi Murakami, Raymond Pettibon, Tony Tasset, Jason Fox and Daniel Hesidence—as well as a booth devoted to the recently established Feature Hudson Foundation (FHF), which includes works by many other artists from the gallery. “Part of the motivation for this project and the foundation was to ensure that Hudson’s work and his legacy doesn’t get forgotten somehow.” A 2004 interview with Hudson by the artist Dike Blair, reprinted in part below, shows just how much the late dealer’s uncanny perception of the art world still resonates today.

Dike Blair: What do you think about what museums are doing these days?

Hudson: They need to flee from hipness and the current notion of art as fun, and ditto for artists, galleries, and collectors. Museums are the big news these days, as their actions and changes deeply shape the art world. There should be a critical examination of such things as their reorientation toward mass entertainment and huge scale, and the expanding power of their education departments and their pervasive audio tours, which seem to churn out like-minded fact followers rather than observant eyes. Whatever happened to the museum as a place of study, aesthetics, and the subjective? Or the quiet time [spent] wandering around a museum deep in thought or ecstatic with emotion? Perhaps museums should institute one silent day weekly. Also, why are museums collecting works by artists who have had fewer than three or four one-person exhibitions? And finally, curatorial positions should be created for those with training outside academia.

Speaking of academia, do you have any advice for the art student?

Hand in hand with the museum issue is the art school: the making of professional artists who are busy with positioning themselves in careers. These years, it’s probably better to develop out of art school. It’s quite odd now that art-school graduates expect immediate affiliation with a gallery, believing they are already artists of some development. Generally, it requires five or so post-graduation years to disengage from the teacher/school influences and create one’s own effort. At this point I’ve stopped attending graduate and undergraduate art-school exhibitions as a way to remain in touch with younger artists and art. I’m looking outside the box.

It seems we could all use some of that.

Exactly. There are many ways to get outside the current commodification of art. For collectors, I’d say, turn your back on the obvious, and favor collecting art as a passion, a curiosity, or for discovery. I even think that collecting art as decoration seems more interesting than as investment. Investment collecting is seriously changing art in a bad way. Critics could be less agenda-oriented, and artists more severe with their editing and more honest with their selection of style and subject matter. Galleries should avoid art made for easy consumption. We should all pay less attention to the salesmanship and showmanship of auctions and fairs, and, of course, be more aware of the not new or hot. And lastly, stop running around trying to see everything everywhere, and spend more time with the richness that is close to home.

Usually your selections and exhibition groupings anticipate or make more concrete certain concepts that artists are reaching for. Does the sense of trend interest you at all?

It is the artists who lead the way. Watch what they are doing and you will see what is happening. Trends do intrigue me, yet because of my hands-on approach, I usually assimilate or reject trends quite some time before they become pervasive. These years, trends are so swiftly advertised and assimilated that it seems obvious to stick to one’s own guns. For me, a glut of anything diminishes its power, and when that occurs, the desire for something else itches. Different people reach their saturation point at different times…

The process is not cut-and-dried. If one has a gallery committed to trends and sales, then surely following the cresting trend is most important. Should one have a personal gallery, one based on the owner or director’s vision and ideals, or even a specific commitment to art and artists, then one follows some thread or intuition regarding the matter of when to grasp and when to let go.

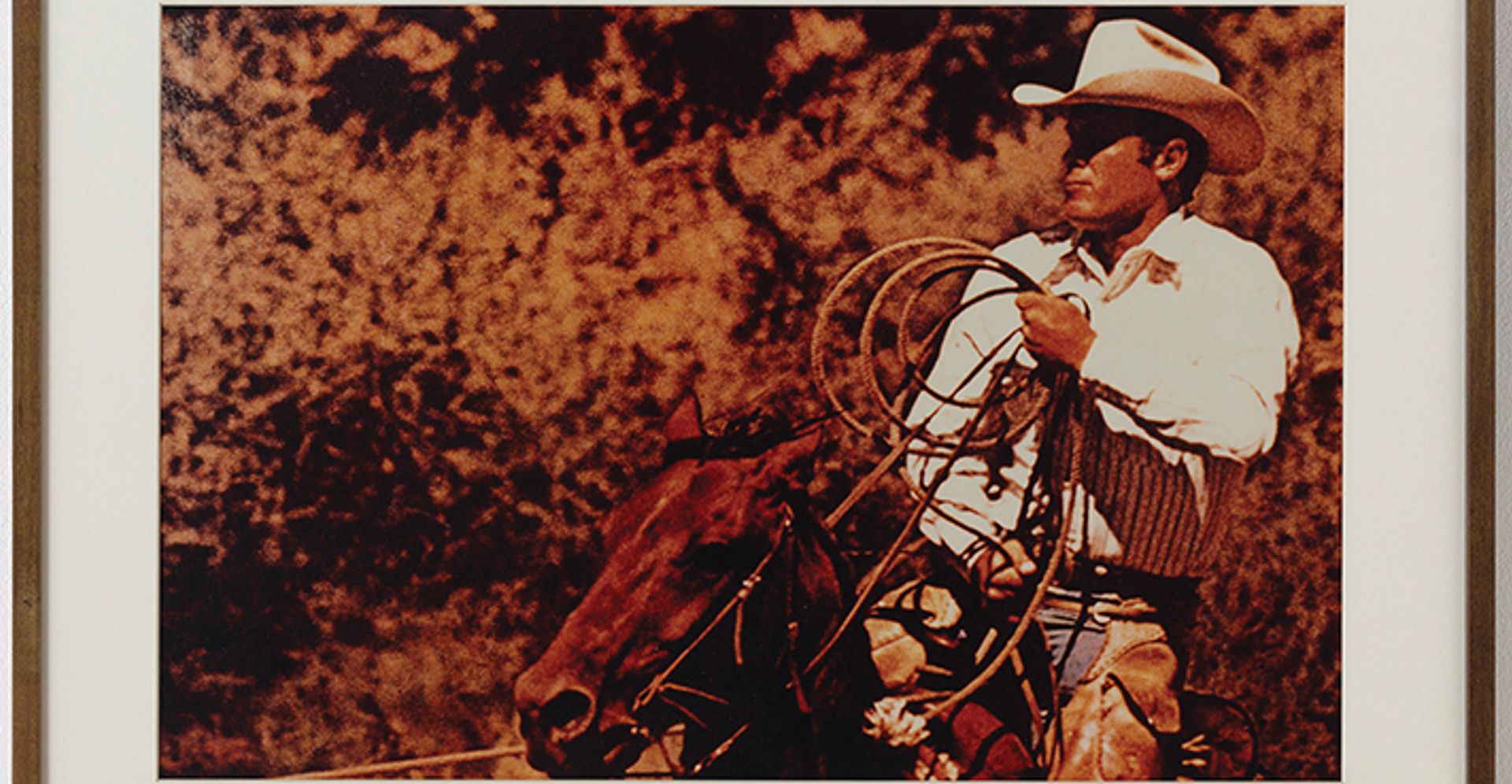

Hudson opened Feature Inc in the city in April 1984 with an exhibition of Richard Prince’s rephotographs Richard Prince. Courtesy of Gagosian

Your reputation is as an artist-friendly gallery. Your practice of looking at artists’ slides and responding with a written note is legendary. Why did you start doing this?

Sometimes those notes, which I’ve written since day one, cause a backlash. The most oppressive response yet, and [one that] truly shook me, [and made me question] my making any comment at all, was “So who the fuck do you think you are—God?”

Artists put their ego, and then some, on the line when they solicit a gallery for representation. It’s an embarrassing if not demeaning process, and it’s even worse if the gallery being approached is one of the artist’s favorites. My concern has been to look at the work in terms of my interests and its possibility for exhibition at Feature, and ever so briefly and candidly respond to its form and content, execution, and its potential to evolve. With some frequency I request an update in a year or so. One artist presented me with work for nine years and each year it was closer and more ready, and then finally—shit happens. Now he is affiliated with Feature and having a visible success.

How do the sheer number and intensity of these exchanges not overwhelm you?

The lack of a wall between my office and the gallery’s exhibition space is a joy but also a problem that I’ve not been able to resolve. So far, my best solution has been to partially obstruct the entrance to the office area with a bookcase. The back of the bookcase, which faces the exhibition space, is an inoperable door. This hints at privacy while allowing for easy access to the office and the storage space behind the office. Yet it hasn’t at all worked well in creating much privacy. Visitors are frequently interrupting my work with mundane questions, or unaffiliated artists’ needs drive them to introduce themselves, something I find annoying as I am almost always quite obviously working…

Do you think Chelsea gallery architecture has impacted the art?

Well, I wouldn’t exactly call it architecture. Again, in scale, administrative layout, and personality—the suits—we see business at work, the corporate model, which I don’t find rewarding or wish to encourage. Distantly related, and interesting to me, is the manner in which the galleries, perhaps due to the overabundance of concrete floors, seem to have become an extension of the sidewalk, almost as if there were no door. And so we have a further breakdown of public and private. Casual strollers, rollerbladers, carriage pushers, cell phone talkers, shoppers, lunchers, et al, move in and out of the galleries, traveling at a near consistent speed. While the democracy of that seems a good thing, somehow the art and the possibility for involvement with art suffer. With that type of situation, how may one have much of an internal experience, though there is more and more art that doesn’t want or need that manner of experience?

Generally, exhibitions at Feature areabout interior experiences, and for some time, to encourage that sensibility, I’ve been contemplating installing parquet floors in the gallery. There would be an anteroom for shoes, bags, carriages, packages, etc, felt slippers for all, and relative quietness, of course, and only five or six people would be allowed in the gallery at a time. All that is scary, as it reeks of the genteel privacy against which so many have rebelled, myself included. Yet it seems right for the time, especially as it is not the dominant mode.

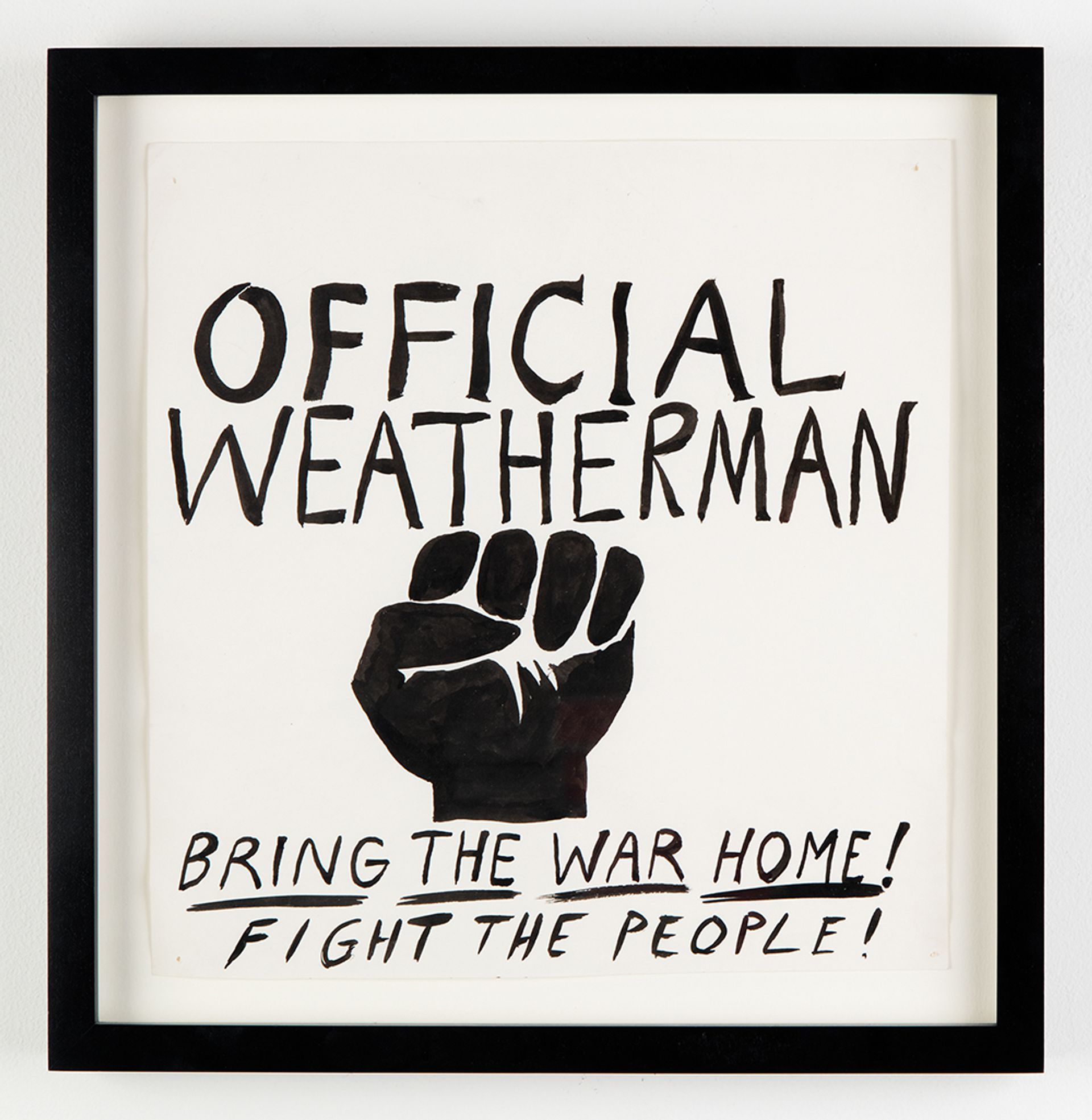

The gallery moved to New York in 1989 jumped around a number of spaces downtown, including a shortlived stint at 276 Bowery Courtesy Feature Hudson Foundation

Many consider your spaces eccentric.

Part of that, I think, comes from the fact that Feature presents multiple exhibitions simultaneously. The current Feature uses its tiny mezzanine space as a discrete exhibition area, and we have an inoperable door space on West 20th Street known as “The Wrong Gallery”. There are so many interesting artists whose work should be seen and injected into our art discussions and art markets that no space should be left unused. It is the responsibility of the galleries to challenge and broaden the market, not to acquiesce to it. One goes to art for expansion, striving, and perhaps for some experience of an “other”. I’m rather opposed to art being made or presented to further satisfy more of the same.

Recently I heard a rumour that a collective of the larger contemporary art museums was considering commissioning artists to create large works, which would then tour all their spaces. You can see the dollars and careers at work luring the artists to produce works that fit within the content restrictions and scale opportunities of the museums. Given that so much is at stake, you can be assured that such a programme will provide us with yet more products of fine entertainment—or is it fine products of entertainment? Art is such a fragile thing, so easily perverted, and in the long term, commissioned works are generally lesser works.

In closing, and very generally, what has your experience as a gallerist taught you?

One of the great things about ageing and having the gallery for 20 years is that the cycles by which things come and go and return yet again become humorously obvious. The notion of the new appears in a more realistic perspective than we are generally willing to acknowledge, one involved with novelty, fashion, and style. As a result, art with deeper levels of personal meaningfulness has become increasingly important. In terms of artists, those with sincere, personal investigations hold greater magnitude, regardless of much else. It’s all very freeing to be rid of this new thing, and as the urgency for mapping or recording this immediate moment decreases, a much larger world is open to appreciation.

And if you weren’t a gallerist, what might you be doing?

Chef for a tiny restaurant. Gardener. Sanskrit scholar.

Four artists who got their big break at Feature Inc

Courtesy of Stephen Friedman Gallery.

Tom Friedman

Showing with Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

After studying in Chicago with Tony Tassett, another Feature artist, Friedman worked closely with Hudson for more than 15 years. In his eulogy of the dealer, Friedman said: “He understood the development of an artist and their vision. He could see so clearly the evolution of consciousness of an artist, and he knew how to push the work to the next level.”

Raymond Pettibon; Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/Hong Kong.

Raymond Pettibon

Showing with David Zwirner, New York

Hudson included the artist in Feature Inc’s 1987 group show Head Sex, when the gallery was still in Chicago, and continued to work with him for nearly a decade.

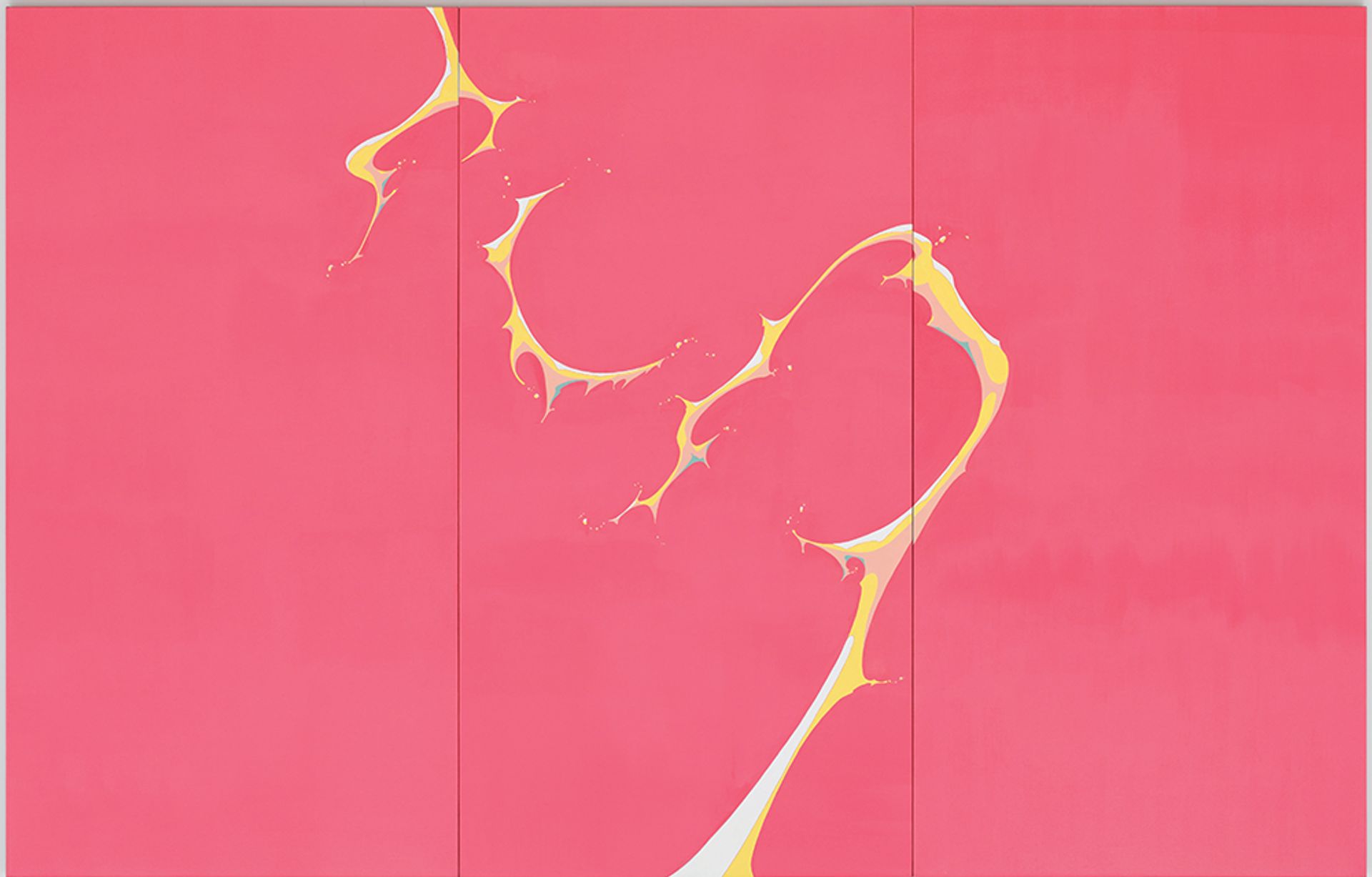

1997 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Photography Rob McKeever

Takashi Murakami

Showing with Gagosian, New York

Hudson gave the Japanese artist one of his first solo shows in the US in April 1996—and treated him to an Italian dinner when two of his anime-inspired sculptures sold. “Years later, I started my own gallery and I now often communicate with young artists myself,” Murakami says. “As I do so, I try to make everything transparent, frankly explaining the market structure and the standing positions of young artists in it, just as Hudson had done for me.”

Lee Thompson; Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

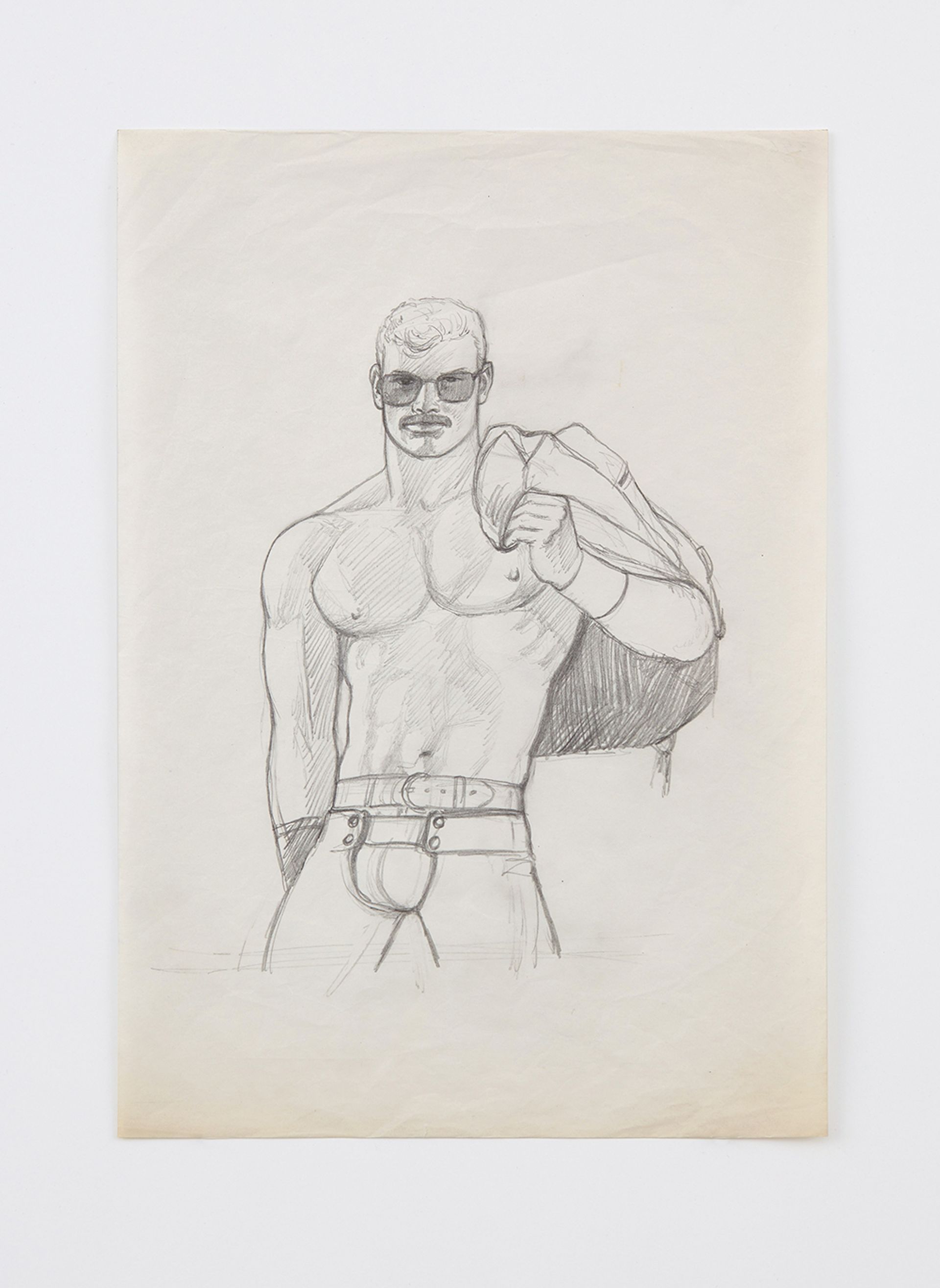

Tom of Finland

Showing with David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles

Hudson brought the artist’s homoerotic work to the masses. In his interview with Blair, the dealer remembered one show when “a busload of people… wandered into Feature. A woman, say in her 60s, came in, carefully looked around, left, and soon returned with a male/female couple of a similar age. They were in the gallery for quite some time. On their way out, as they passed by the office, they were quietly speaking among themselves, and the woman from the couple mentioned that she thought she had just seen pornography, and the other woman replied, ‘Yes, but did you see the way they were drawn?’ Overhearing that left me floating.”