Adrian Piper: a Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965-2016

Museum of Modern Art, until 22 July

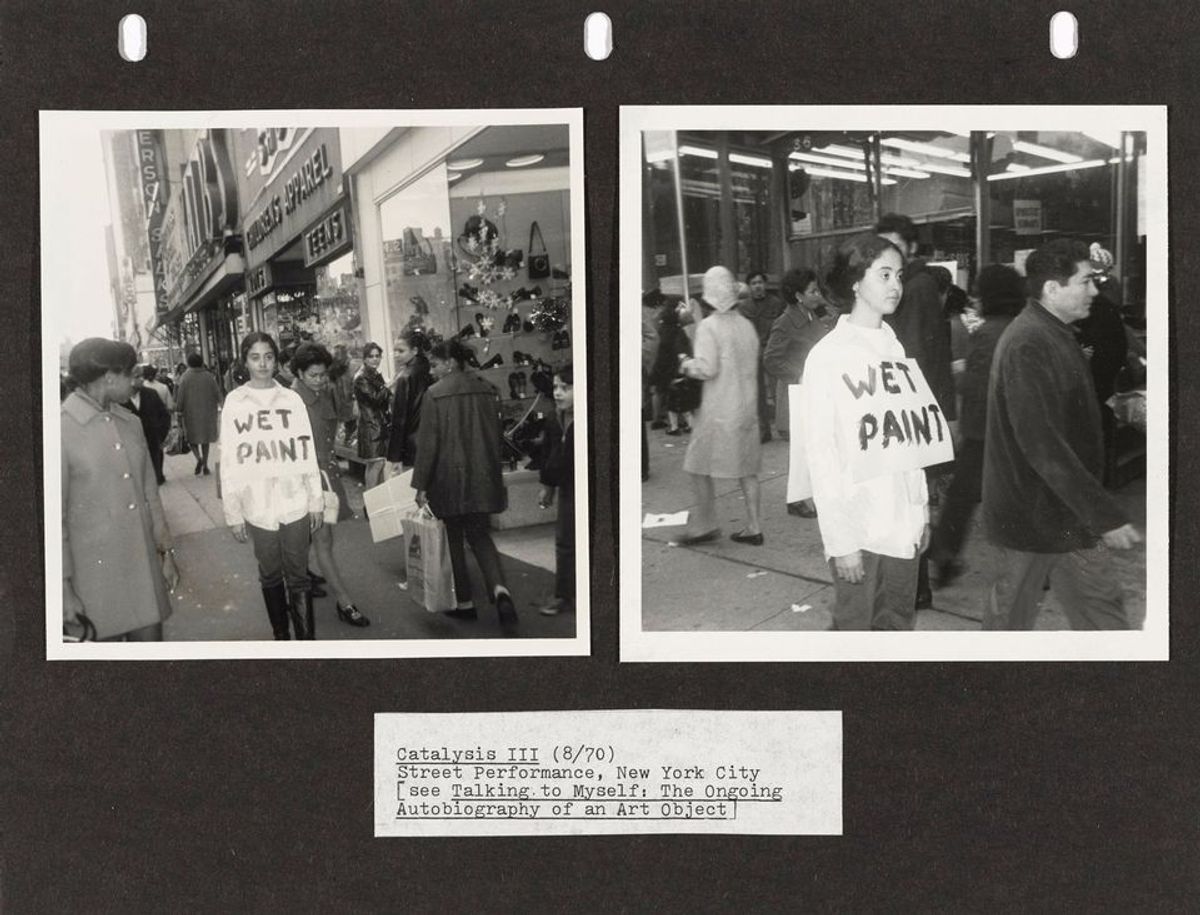

How does an exhibition tell the wide-ranging story of the New York-born, Berlin-based artist Adrian Piper? Her work began with Conceptualism in the 1960s before morphing into socially engaged art looking at race and otherness, and encompasses performance, video, sound, installation and drawing, among other media. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) has risen to the challenge by dedicating its entire sixth floor to Piper’s retrospective of around 280 works—a first for a living artist. The installation What It’s Like, What It Is #3 (1991)—first shown at MoMA and recently acquired by the museum—“in a nutshell explains what [Piper’s] work is about”, says the show’s co-curator Christophe Cherix. The white room with bleachers feels like entering “a Minimalist sculpture”, Cherix says. A square column in the middle shows a video of a black man who blankly says phrases like “I am not scary” or “I am not lazy” to challenge, and highlight, racist assumptions. “It’s never giving up the rigour of Conceptual art, [seen] in the shape of that room—but also trying to bring that together with the social realities [of the] time.”

Anselm Kiefer: Uraeus

Public Art Fund, Rockefeller Center, 2 May-22 July

As Frieze New York’s white tent goes up on Randall’s Island, a different kind of monumental structure will be rising at Rockefeller Center: Anselm Kiefer’s first site-specific, outdoor, public commission in the US. The sculpture, titled Uraeus, is a book with eagle’s wings spread open 30ft-wide, atop a 20ft-tall column, with a snake coiling up it and more books clustered around the base. The title and much of the imagery of Uraeus relate to ancient Egyptian mythology, but also to Kiefer’s own visual lexicon, in which books and wings are a mainstay. The work is made largely of lead, a favourite material for the artist because of its softness and association with alchemy. “There are motifs [in Uraeus] that are very familiar to anybody who has followed his work,” says Nicholas Baume, the director and chief curator of the Public Art Fund, which organised the presentation. “But I think what’s really interesting is that this is a significant new articulation of those things.”

Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-85

Brooklyn Museum, until 22 July

In the middle of this wonderfully unruly exhibition, travelling from Los Angeles’s Hammer Museum, is a short 1982 video by Letícia Parente called Tarefa 1 (Chore 1), in which a clothed woman, presumably the artist, crawls onto an ironing board and lays face down while she is pressed head to toe with the iron. It’s not clear whether the iron is hot. The show also includes a 1975 video in which she uses needle and thread to sew the words “Made in Brasil” onto the sole of her foot. Her hand and foot are both remarkably steady. In such works Parente re-enacts, with a sly sense of humour, the routine violence committed against women by men and their military and maybe even corporate instruments. In effect, she fiercely controls the narrative of being controlled.

One Hand Clapping

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 4 May-21 October

Whether they use oil paint, VR, sound art, animation or robots, the five artists commissioned to create new works for the Guggenheim Museum are all thinking about the future. “There is a single-vision, homogenous way of understanding the future that is based off wealth and technological developments, and enforced by globalisation,” says the show’s curator Xiaoyu Weng. “We’re losing our imagination for a different kind of future that is locally embedded.” For this third and final installment in the Robert H.N. Ho Family Foundation Chinese Art Initiative, each artist has made work from their “personal, localised perspective”. For example, Duan Jianyu’s oil painting explores the tensions in China’s transitory places where the urban meets the rural, while Wong Ping’s colourful animation Dear, can I give you a hand? (2018) focuses on China’s aging population against the backdrop of the digital economy.

Huma Bhabha: We Come in Peace

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden, until 28 october

“We come in peace”, the often-copied line voiced by aliens from the film The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), is also the title of the Pakistani-born, New York-based artist Huma Bhabha’s bronze sculptures unveiled last month on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Roof Garden (until 28 October). In an interview with the show’s co-curator Sheena Wagstaff, Bhabha says of the works: “Maybe the way the two figures on the roof connect [is] by being summoned, coming when the other calls. I think if the sculptures were seen separately they would inspire darker interpretations, but the combination of the two on the Met’s roof creates a dialogue and a narrative that implies some kind of communication from which hope can derive.”

Like Life: Sculpture, Colour and the Body (1300-Now)

Met Breuer, until 22 July

“With so many dramatic cultural changes taking place nowadays, we felt an urgent need to critically reassess our preconceptions of the history of the body,” says Sheena Wagstaff, the co-curator of this show, which includes 120 objects dating from the early 14th century to the present day and broadly considers how sculpture has sought to replicate the human form, particularly through colour. Big-name artists, including Donatello, El Greco, Edgar Degas, Louise Bourgeois and Jeff Koons, are represented, but the exhibition is also notable for its unusual loans, such as a Sleeping Beauty from Madame Tussauds wax museum in London and a breast-shaped porcelain cup that Marie Antoinette used in her sumptuous pleasure dairy at Versailles.

Mel Chin: All Over the Place

Various venues including Queens Museum, until 12 August

“When you’re dealing [with] social [issues], it’s best to try to deliver something,” says the artist Mel Chin, who has a retrospective co-organised by the Queens Museum, No Longer Empty and Times Square Arts. “Being aware and informed is not enough.” For the opening piece of the multi-site exhibition, the artist collected plastic water bottles that the residents of Flint, Michigan, have been forced to drink from since their local water supply was contaminated by lead. The bottles were sent to North Carolina and transformed into fabric that was then transported to the St Luke NEW Life Center in Flint. Here, jobs were offered to in-need locals who sewed the recycled material into clothes, conceived by the New York fashion designer Tracy Reese. The result is nine different styles and a prototype for a possible clothing line, now on view at the Queens Museum’s Watershed Gallery.