The amicus brief signed by more than 100 museums concerning the Trump administration’s travel ban should shame the justices of the US Supreme Court. It should appal them to read that exhibitions have been cancelled because of it; embarrass them that, as it says, even artists “not directly covered by the Order [the travel ban] have cancelled museum events in the US because of the uncertainty and fear that the Order has created for many foreign nationals”; and convince them that, if indeed the ban aims to stifle terrorism, artistic exchange and dialogue “foster tolerance and understanding of others” and protect us from those threats.

The argument that the ban deprives Americans of important art, performance and scholarship, and denies people insight into the rich cultures of the countries affected, should be enough. But given the ugly nationalist climate that President Trump has promoted, another argument in the brief is perhaps shrewder. It states that the ban “will have a significant negative impact on the [museums’] ability to conduct the kind of cross-cultural, dynamic global exchanges that make Americans more informed, and thereby, America stronger”. Aside from the compelling point about knowledge representing power (a fact that clearly terrifies the lying president), the idea of appealing to patriotic sentiment makes sense. Because many of the great developments in American art emerged precisely from the engagement between America and artists from overseas, whether they were visitors or emigrés. To paraphrase a familiar slogan, foreigners made American art great.

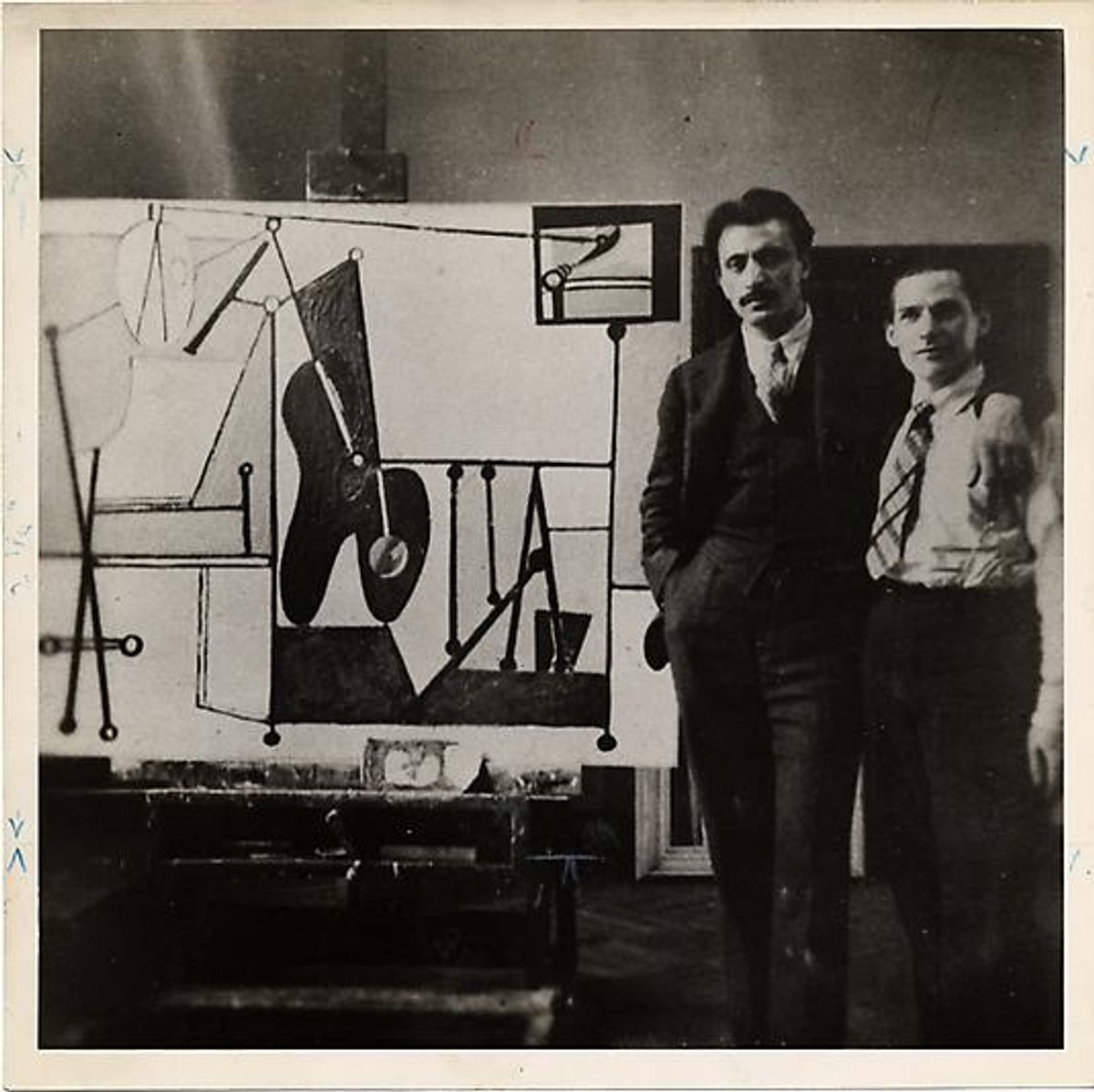

We need only look at the post-war period, the moment when New York usurped Paris as the leading artistic centre in the West. Abstract Expressionism, the standard bearer for this new golden era of American art, was a movement dominated by people and ideas from outside America. Willem de Kooning moved from the Netherlands to the US as a 22-year-old stowaway in 1926. He quickly fell in with artists who called themselves the Three Musketeers, the American Stuart Davis and two artists that had escaped persecution: John D. Graham, born Ivan Dambrowsky in Kiev, who fled Russia after having been imprisoned by Bolsheviks; and Arshile Gorky, who arrived in America having escaped the Armenian genocide and witnessed his mother’s death from starvation. These three invited De Kooning to be the fourth musketeer and the seeds of De Kooning’s language developed through that relationship.

Even the most stereotypically all-American AbEx artist, Jackson Pollock, was profoundly influenced by a direct encounter with a visiting artist: he attended the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros’ Laboratory of Modern Techniques in Art, where the latter expounded his theory of “controlled accidents”, and students explored experimental methods, including dripping household paints and moving dynamically around floor-based supports, that later became Pollock’s signature technique.

When young artists sought to escape what Calvin Tomkins called “the stifling dominance of Abstract Expressionist painting”, they turned to another outside influence: Marcel Duchamp. An inspired milieu emerged in Black Mountain College in North Carolina in the late 1940s—around students Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly, and regular visitors John Cage and Merce Cunningham—and burgeoned in New York alongside artists such as Jasper Johns. It would never have made such a marked shift had the artists not been influenced by, and then in steady dialogue with, Duchamp, who was then in a second stint in the US having fled France during the German occupation. Then there is the role of Josef and Anni Albers, the Bauhaus linchpins who left Germany as the Nazis took power and taught at Black Mountain College. Rauschenberg memorably described Josef as “a beautiful teacher and an impossible person” and wrote: “Years later… I’m still learning what he taught me.”

These are just a smattering of the kind of “cross-cultural, dynamic global exchanges” that the amicus brief describes and that transformed American art as it began to dominate Western dialogues. When De Kooning spoke of his meeting with Gorky and Graham in 1920s New York, he said: “It was nice to be foreigners meeting in some new place.” One of the many human deprivations of the travel ban is that it risks destroying the possibility for similar collisions to occur in the US today.