Technology’s rising influence is affecting cultural institutions just as much as every other aspect of society, as was made clear at the annual conference Legal Issues in Museum Administration in Boston last week (18-20 April), co-sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution and the American Law Institute. Our reporter attended the event and came away with the following highlights.

The dangers of high-tech art

Museums are increasingly using new technologies to enhance and personalise the visitor experience, from augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) to robots, Lauryn Guttenplan, the associate general counsel at the Smithsonian Institution, told the gathering. Technology that is part of a work can create legal issues—which lawyers on the panel brought to life by analysing case studies from the exhibition Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today at the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) Boston (until 20 May). The show asks how art “in every medium has been impacted by new technologies”, its assistant curator Jeffrey De Blois told the group.

It was enough to make a lawyer shudder—and the lawyers on the panel did not shy from sharing their (many) concerns.

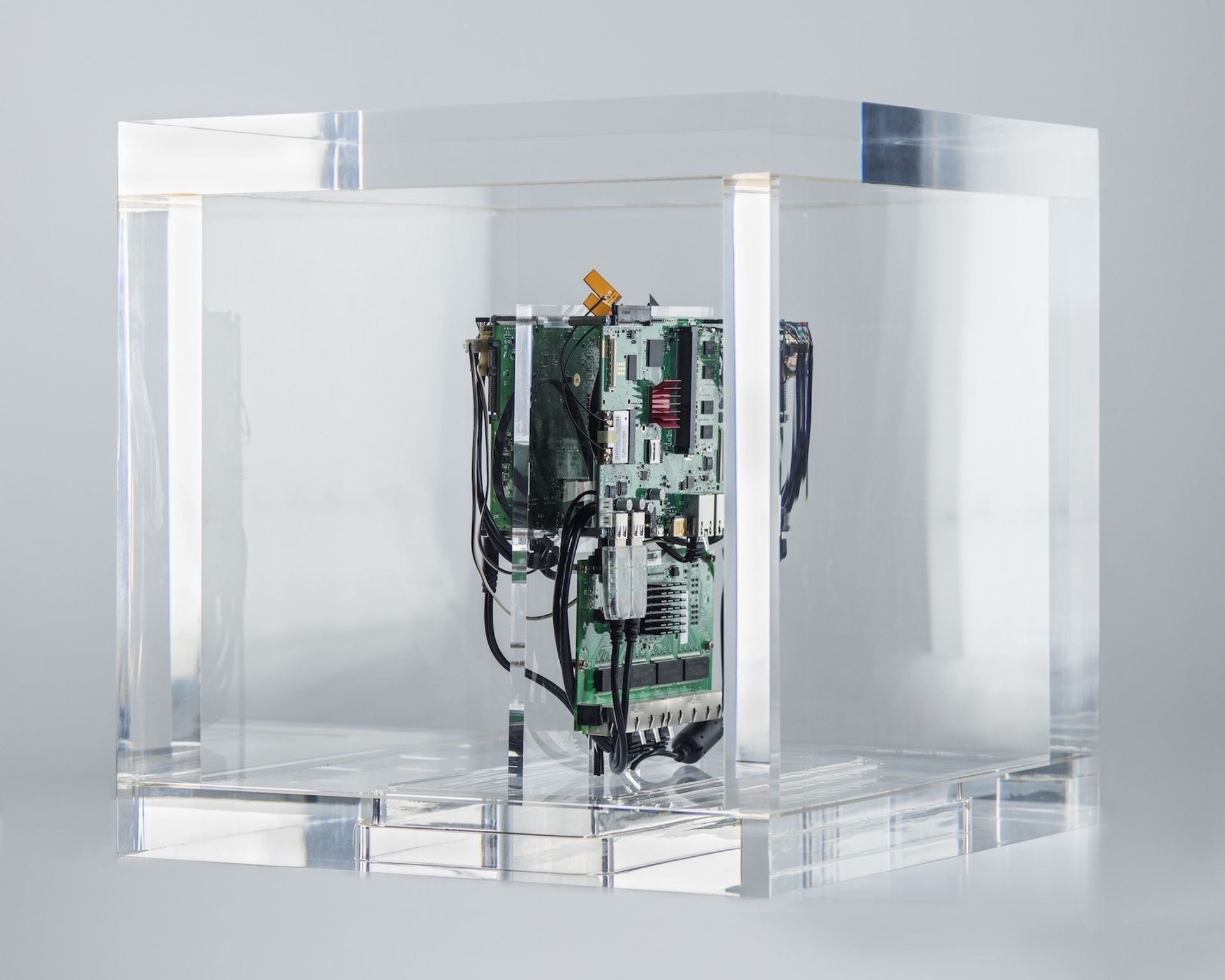

Trevor Paglen, Autonomy Cube (2014) Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York

One sculpture, Autonomy Cube (2014) by Trevor Paglen, creates an open wifi hotspot through which visitors can cruise the internet undetected, via the global Tor network, developed for the US Department of Defense and comprised of volunteer servers and relays that anonymise data. The work sets up an interstitial, anonymous space that resists “trends of surveillance” and “creates a bubble within society that allows freedom of expression and exploration”, De Blois said. “We don’t know what people are doing in the space.”

Exactly, the lawyers said. “All I see is problems,” said S. Jason Baletsa, a counsel at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Putting forward the worst case scenario, a Tor router can create “a secret internet for drug dealers and paedophiles” or purchasers of weapons, he said. “I feel uneasy about inviting the public to roam the dark web.” Law enforcement officials could seek information from the institution or its internet service provider, he added, because users' exits from the hotspot would show the museum as their last location.

But the ICA “knew the risks” and decided to take them on, De Blois said, “for the sake of the exhibition and because of the weight and power of the piece”. The question for the lawyers then became how to mitigate the risks. In such cases, a museum could clear the risks in advance with the museum board, discuss the project with its internet service provider and notify visitors “of the risks associated with using this,” Baletsa advised. “That would probably ruin this piece,” De Blois said.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, CybeRoberta (1995-96) Courtesy of the artist and Bridget Donahue Gallery, New York

Two other works in the show, Lynn Hershman Leeson’s CybeRoberta (1995-96) and Tillie, the Telerobotic Doll (1995-98), are a pair of toys with concealed surveillance cameras that can be controlled by visitors in the gallery or online, sending videos of their surroundings—including images of museum visitors—to the dolls’ websites. The dolls are “a little creepy” to a lawyer, Baletsa said, cautioning that visitors would need to be put on notice that they could be videotaped and their images broadcast around the world. The ICA has done just that, De Blois said, through notices and museum staff in the galleries. What about unlawful wiretapping, if a visitor’s phone conversation is recorded? “The dolls do not record audio,” De Blois confirmed.

Another work in the show, which the ICAB commissioned, is the Canadian artist Jon Rafman’s site-specific View of Harbor (2018), an eight-minute VR “doomsday scenario” in which a tidal wave destroys the museum in an “apocalyptic landscape”, De Blois said, including tormented bodies. “Are visitors going to flee the tidal wave and back into a wall?” Guttenplan asked. “It sounds like a tort claim waiting to happen.”

In addition to notifying visitors about the content of the experience, she noted that VR projects can raise legal issues about what software or hardware the museum is borrowing or buying, and disability access. “Visitor response has been great,” De Blois said. The ICA brought on a public relations person to deal with the work, provided notices that viewers could experience nausea, and recommended that parents try out the VR before letting their children do so. “It’s a balance. You don’t want to scare off museum visitors,” the curator added.

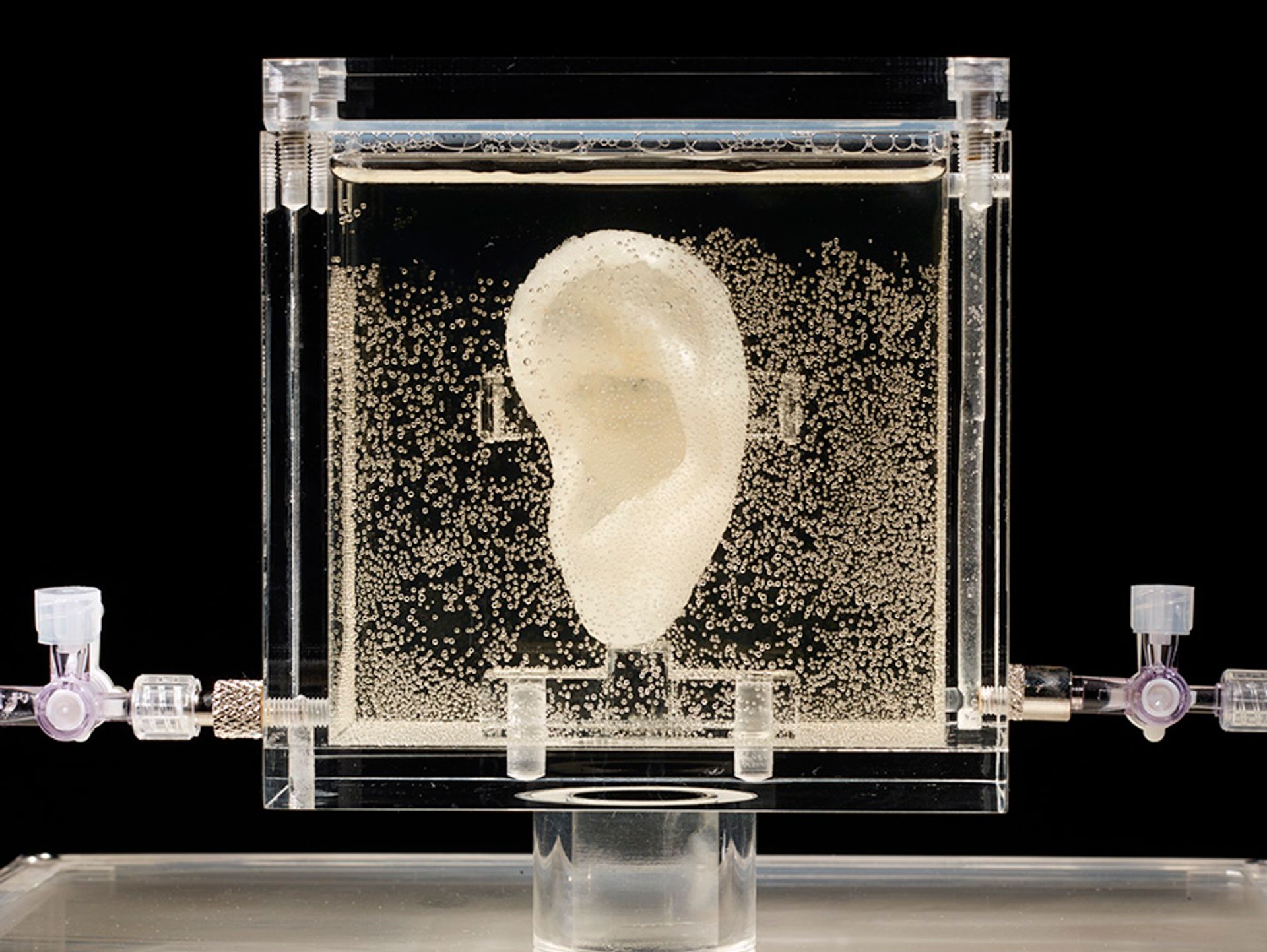

Diemut Strebe, Sugababe (2014) Courtesy of the artist

When artists and engineers collaborate

Diemut Strebe, the artist in residence at the MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology, gave the conference’s keynote address, describing how art, science and technology interconnect in her works. In Sugababe (2014), Strebe created a living replica of Vincent Van Gogh’s cut-off ear using human tissue and genetic engineering, to explore the implications of “recreating a historical person after death”.

Currently, Strebe is creating works using nano-engineered materials, collaborating with the MIT professor Brian Wardle. In Redemption of Vanity, Strebe has taken a $2m 16-carat yellow diamond, donated by L.J. West Diamonds in New York, and visually negated the surface with a coating of carbon nanotubes, known as the blackest material on earth, which absorb 99.965% of light. The coating makes a 3D object appear “like a flat silhouette. Obviously, this is aesthetically a very interesting material,” Strebe said. By using carbon to devalue a $2m piece of bling—also made of carbon—the work challenges art market assumptions, raising questions about how value is attached to luxury objects.

The project is also a statement against the British artist Anish Kapoor’s 2016 purchase of the exclusive rights to Vantablack, another material made of carbon nanotubes, from the British manufacturer Surrey NanoSystems. “Strebe and Wardle use a different composition of carbon nanotubes, which will be available for any artist to use,” MIT says on its website.

Felice Grodin: Invasive Species at PAMM Courtesy of the artist

Augmented reality and data collection

A number of museums are using AR, such as the Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) which commissioned the artist Felice Grodin to create a work about climate change. Visitors could see Grodin’s creations—invasive species crawling across the museum premises—on their own phones and devices through the museum’s mobile app. Because of costs, rather than hiring an AR specialist, the museum decided to use Apple’s AR kit, said Thérèse Vento, PAMM’s general counsel. But in light of the scrutiny over Cambridge Analytica’s unauthorised use of data gathered from Facebook, what legal issues can arise when a museum works with a third-party app provider?

For example, a museum may want to inform users that third-party providers could access and collect their data. But this may not even be correct if the provider’s policy relates only to its web activities, said Cynthia Larose, a lawyer at the Boston law firm Mintz Levin. Presumably, there would then be no agreed limits on what the third party can do with visitor’s data. Larose advised museums to seek to limit what data the app provider will have access to or, at least, do their due diligence to find out what information they will collect.