Does anyone see us the way we look to ourselves? Even a great portrait can’t do the trick. It’s still another person’s interpretation, and even when that interpretation is more representative than an internal mirror, the portrayal may not flatter the ego. “It’s impossible to hold a smile for three days,” said the art bookseller Dagny Corcoran, explaining her uncharacteristically grim expression in a work included in David Hockney: 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. When the artist is Hockney, however, and the subject is one of his oldest friends, she’s willing to cut him some slack.

The real subject here, and the source of each portrait’s fascination, is the tension between self-image and outward appearance. (That seems true for the fruit in the one still-life as well.) Executed in his Hollywood Hills studio between 2013 and 2015, and painted in vibrantly coloured acrylics on 48-by-30-inch canvases, Hockney didn’t play favorites, whether they were the Lacma curator Stephanie Barron (an acquaintance of 40 years), his housekeeper, his dentist, his siblings, the then-11-year-old, suited-up son of the artists Tacita Dean and Matthew Hale, the art dealer Larry Gagosian, or Hockney’s studio manger, J.P. Goncalves de Lima—the only one to hide his face in his hands.

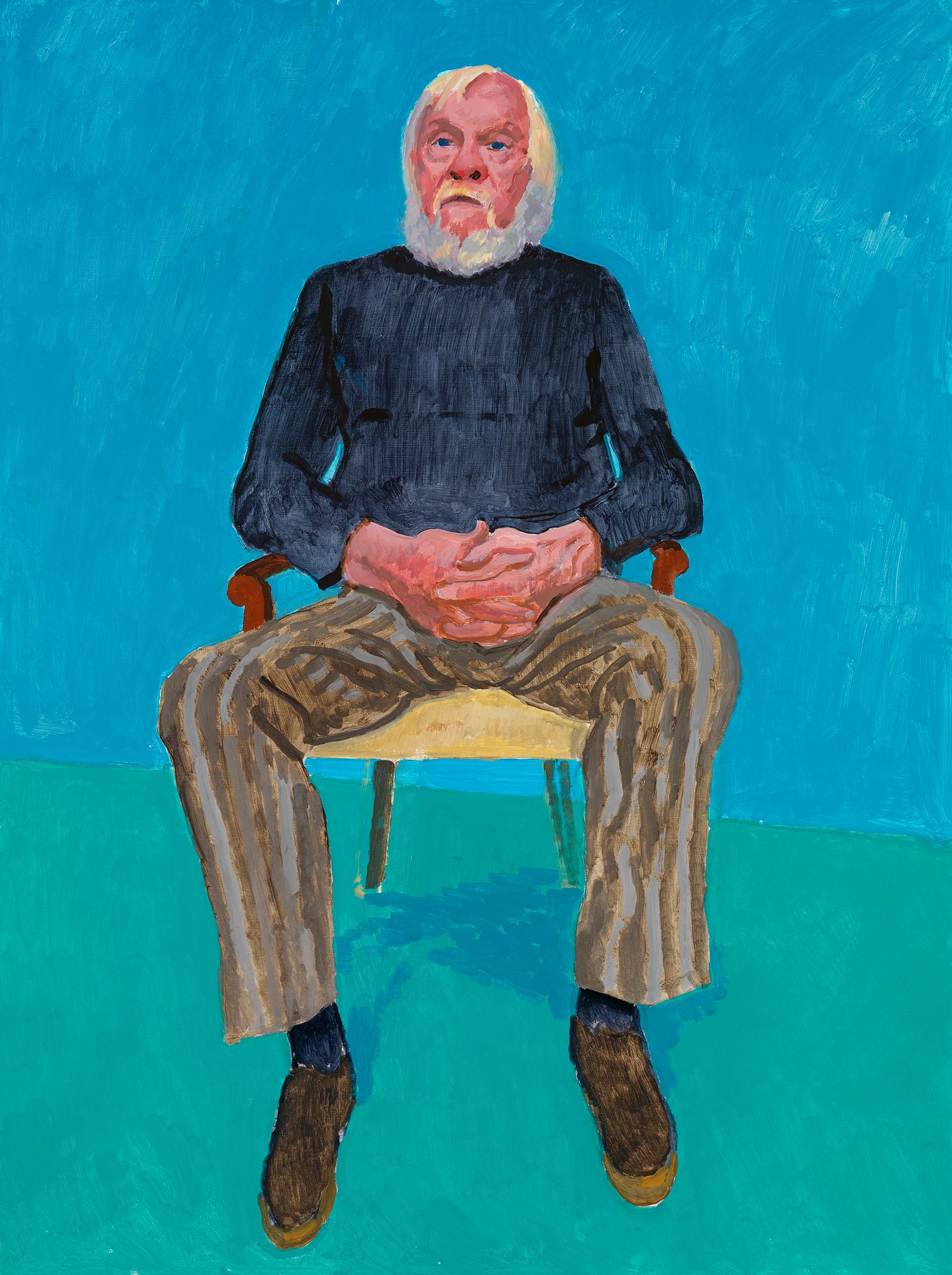

Moreover, each subject is seated in the same yellow, straight-back chair and appears against a deep-blue background set off by a green, purple, or Hockney’s famous swimming pool aqua ground. People wore what they wanted and chose whatever position they could maintain for the requisite “20-hour exposure” of their sessions. In fact, the passing time is the subtext of the whole series, which Hockney considers a single body of work.

David Hockney, John Baldessari, 13th, 16th December 2013 from 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life David Hockney, Photo: Richard Schmidt

Arrayed on deep, terracotta-red walls, details stand out, whether they’re paunches, pigeon-toed feet, clasped hands, crossed legs (as with the publisher Benedikt Taschen), parted knees (John Baldessari), or steely stares (the case with the longtime Yves Saint Laurent communications director Dominique Deroche). Body language is key to the lexicon of personalities in this exhibition, which began a five-city tour last year at the Royal Academy in London before winding up at its only American venue, in Hockney’s adopted hometown, where most of the sitters also live.

Despite the discomfort she felt under the artist’s “intense scrutiny,” Barron—one of the more accomplished curators in American museums—became fascinated with the whole process, including conversations during breaks, and was mightily pleased with the results. “Seeing how quickly he worked,” she says, “was a revelation.”

Fittingly, the show’s finale is a self-portrait—an enormous photomural of Hockney standing in his studio beside the yellow chair, surrounded by recent works. He looks tiny in the space. But, well, you know—appearances can be deceiving.

David Hockney's self-portrait—an enormous photomural of the artist standing in his studio beside the yellow chair, surrounded by recent works