The first public museum and memorial to the victims of racial terror in the US—specifically, the 4,400 African Americans lynched between 1877 and 1950—opens this month in Montgomery, Alabama with the aim of reconciliation during a period of deep unrest. “There is still so much to be done in this country to recover from our history of racial inequality,” says Bryan Stevenson, the founding director of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), which spearheaded the project. “We can achieve more in America when we commit to truth-telling about our past.”

After two years of planning and construction, and having raised an estimated $20m from Google, the Ford Foundation and private philanthropists such as the billionaire activist siblings Pat and Jon Stryker, the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice will be inaugurated with a two-day “peace and justice summit” starting on 26 April. Speakers and performers include the activists Marian Wright Edelman and Gloria Steinem, Al Gore and hip-hop artists The Roots and Common.

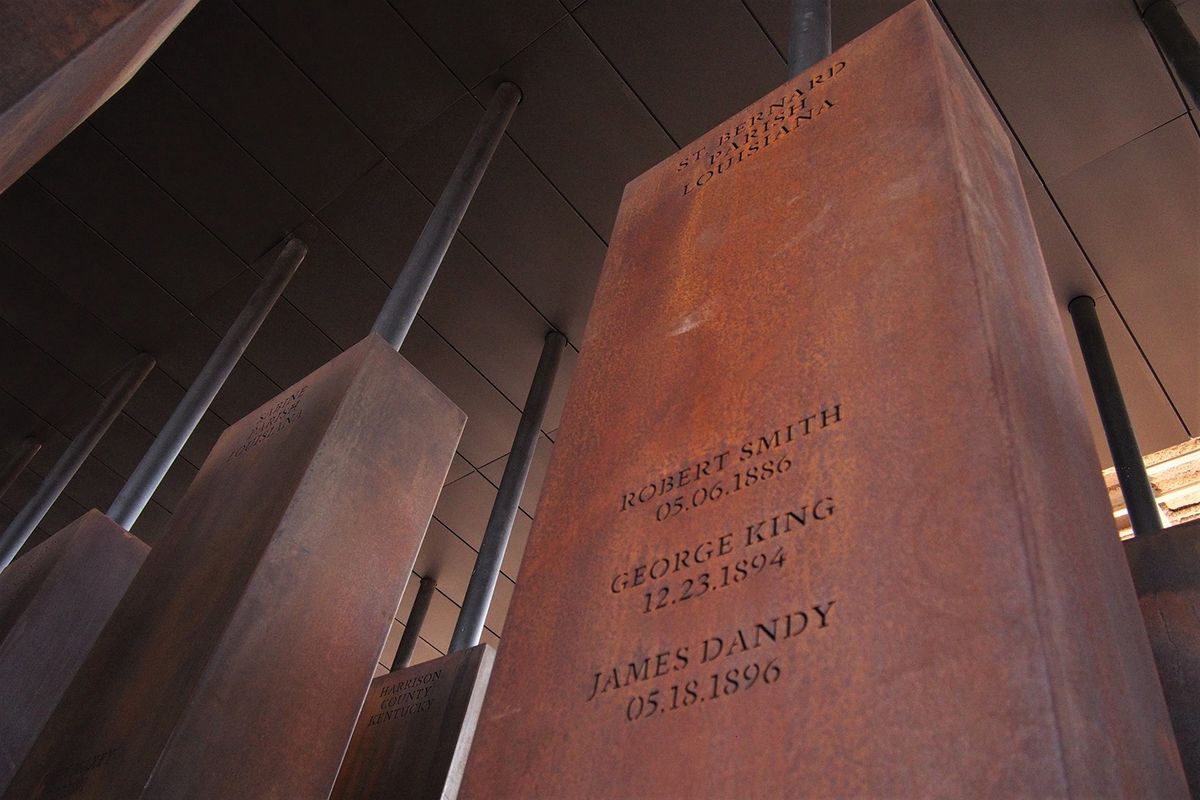

Once inside the sprawling six-acre memorial site, designed in collaboration with the Boston-based MASS Design Group, visitors will be guided through 800 hanging steel columns representing those counties in the US where a documented lynching took place. Each one is engraved with the names of those who were murdered. The pathway through the columns eventually drops so that the slabs hover, body-like, above the visitors’ heads. Next to the main structure lie duplicates of each pillar, waiting to be claimed and erected as monuments back in the listed counties.

“The history of lynching needs to be memorialised in a powerful way and in a place where people can deal with it, where people can integrate it into their vision of history,” says Kirk Savage, a professor of architecture and art history at the University of Pittsburgh, who has studied US public monuments for over 30 years. “Like acts of terrorism—which lynchings were—they have ramifications that are much broader than the horrible events themselves.”

An early rendering of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice Equal Justice Initiative

The structure’s significance is best understood in relation to Montgomery’s nearly 60 statues honouring the pro-slavery Confederacy. On the grounds of the Alabama State Capitol, for example, stands an 88-foot marble monument to Confederate soldiers. A stone’s throw from there, the First White House of the Confederacy aims to relate the story of “when a government was formed from few resources except cotton and courage”, according to its website. Last year, state lawmakers approved legislation to counter what some sponsors called “political correctness” by prohibiting the removal of any monument more than 40 years old. At the same time, the city is where Rosa Parks launched a boycott against segregation on public buses and Martin Luther King Jr led marchers from Selma, Alabama to protest for equal voting rights for African Americans.

“Montgomery has the dubious distinction of being the birthplace of both the modern Civil Rights Movement and the Confederacy,” says Georgette Norman, the former director of the city’s Rosa Parks Museum and a member of the Alabama African American Civil Rights Heritage Sites Consortium. “It was the most unlikely place for a revolution to start and yet it did. And now Montgomery is again front and centre.”

Paired with the memorial, the 11,000-square-foot Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, built in a former warehouse that once held slaves, traces the long arc of racial violence and inequality in the US to the present, when one in every three black men will spend time in prison. EJI argues that “this history continues to shape the present, and that’s one of the reason why we have mass incarceration today” Savage says. “We need to reckon with this history in a real way to solve the problem of racism in this country.”

“The Legacy Museum is so important because it shows us how the legacy of slavery still affects us,” says the philanthropist Agnes Gund, whose Art for Justice Fund awarded a grant to the Equal Justice Initiative last year. “The system of white supremacy that justified slavery was built on many of the same dehumanising stereotypes of black people that exist today. We need more initiatives like the Legacy Museum to illuminate injustice.”

The Legacy Museum will also feature work by artists such as Hank Willis Thomas, Glenn Ligon, Jacob Lawrence, Elizabeth Catlett, Titus Kaphar, and Sanford Biggers. The latter is producing the largest instalment in his series BAM, for which he collects African sculptures from flea markets, dips them in thick brown wax, fires at them with guns and records the process with high-speed cameras. He then takes the remnants, which evoke Classical sculptures with missing limbs, and casts them in bronze.

Jars of soil from lynching sites in the Legacy Museum Brian Palmer/brianpalmer.photos

“They also touch on the violence perpetuated against black bodies by the police, which goes back into all the aspects of the Legacy Museum, showing the whole pathological experience of Africans in America, from abduction in Africa to mass incarceration today,” Biggers says. “I wouldn’t put the pressure on any one institution to change this history,” he adds, but describes the ideas behind the museum and memorial as “something new and very important”.

Another of the museum’s displays is a collection of jars holding soil from lynching sites. Norman helped to collect some dirt from under a tree outside Selma. “We had to uproot so much that has gone down in our history, to unearth the living legacy of someone. It was amazing,” she says. “It was kind of an overcast day. We had just filled the last jar with dirt. Before we could cap them, all of a sudden, the clouds began to part. We just cried.”