Under artistic director Julieta Gonzalez, the Jumex Museum in Mexico City is visibly becoming one private foundation that is genuinely dedicated to serving the public and not just the pleasure of its patron (in this case, collector Eugenio López Alonso.) Take the engaging, “Proposals for a Plaza” by Fritz Haeg and Nils Norman.

Installed outside the institution’s entry, the artists’ arrangement of nature’s architecture—boulders, trees and benches—lends a park-like, town square atmosphere to the plaza in utter defiance of the looming surreality imposed by Carlos Slim’s Museo Soumaya across the way. Emerging from semi-retirement in his northern California commune, Haeg appeared for the 7 April unveiling, amidst yoga classes, dog-training sessions and general social ebullience. “Culture shock,” he remarked, with a nervous laugh.

Leading the pack among the indoor exhibitions is Gonzalez’s Memories of Underdevelopment: Art and the Decolonial Turn in Latin America, 1960-1985. If that sounds like a turgid slog born of academia, take a deep breath.

The show, which premiered last fall in San Diego under the umbrella of Pacific Standard Time, also comes as news to audiences here, following decades when the social and economic consequences of mid-century colonialism escaped the spread of general information. Not artists. Some dared to work within dictatorships. Others took vows of poverty. To all, art meant information and action as well as form.

“It’s encyclopedic!” exclaimed an amazed Pedro Reyes at the show’s opening. It’s also enjoyable as well as enlightening—and not just for a gringa getting her first, truly inside view of the Modernist/capitalist sweep of Latin American cities that enriched the few and failed the many, as led in the early 1960s by European and American industrialists and, in no small part, the Catholic Church.

Blood-curdling shrieks greeted my return for a closer look. The piercing sound came from live parrots squawking for attention from an installation by Helio Oiticica. That seemed an apt metaphor for art meant to raise goose bumps as well as social consciousness, created as it was in response to political corruption, growing poverty, and the marginalisation of vernacular cultures that created Third World divisions and anticipated the globalism we have now.

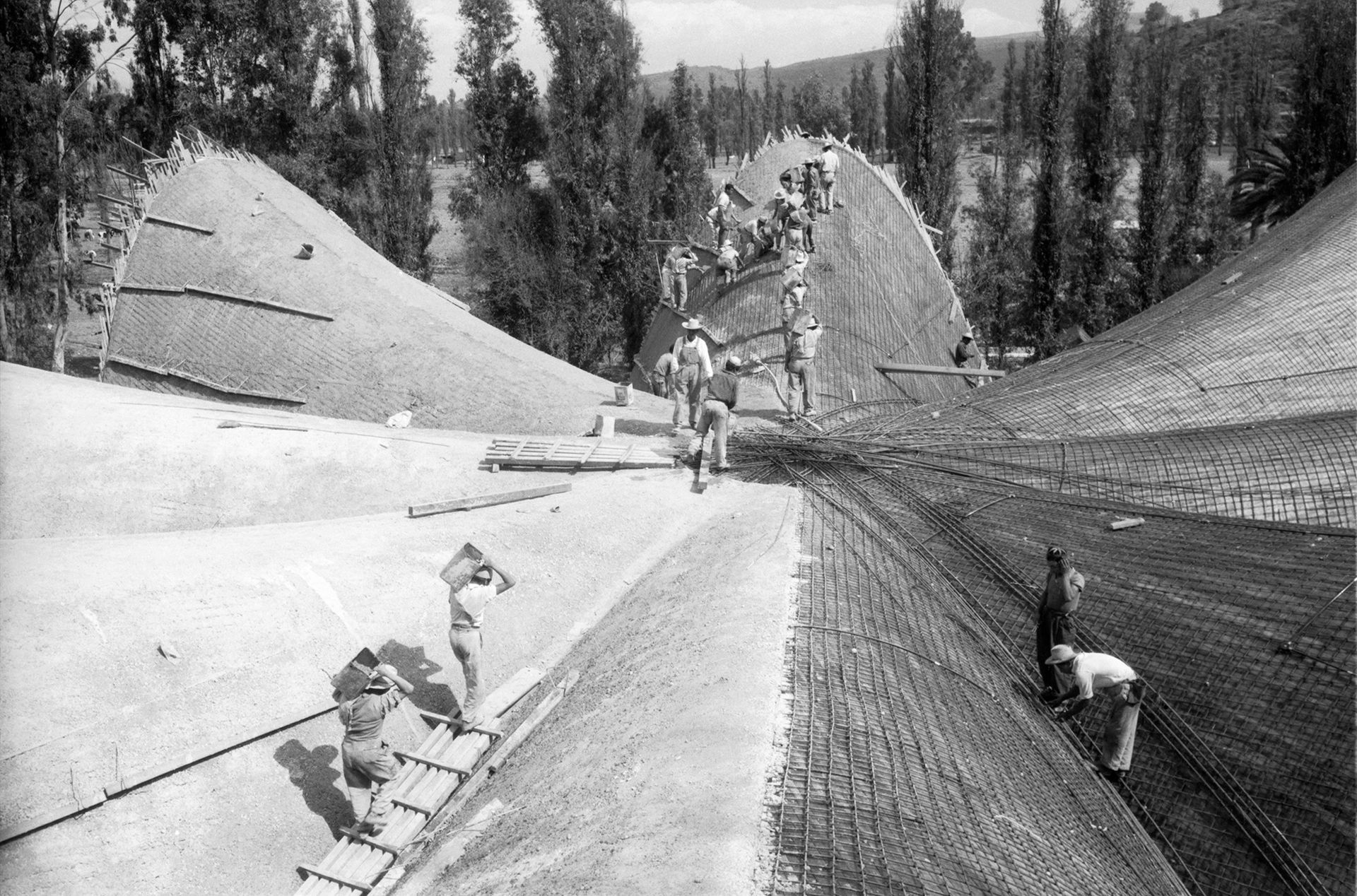

Juan Guzmán Construction of Los Manantiales Xochimilco, Mexico City (1958) Colección y Archivo de Fundación Televisa/Fondo Juan Guzmán

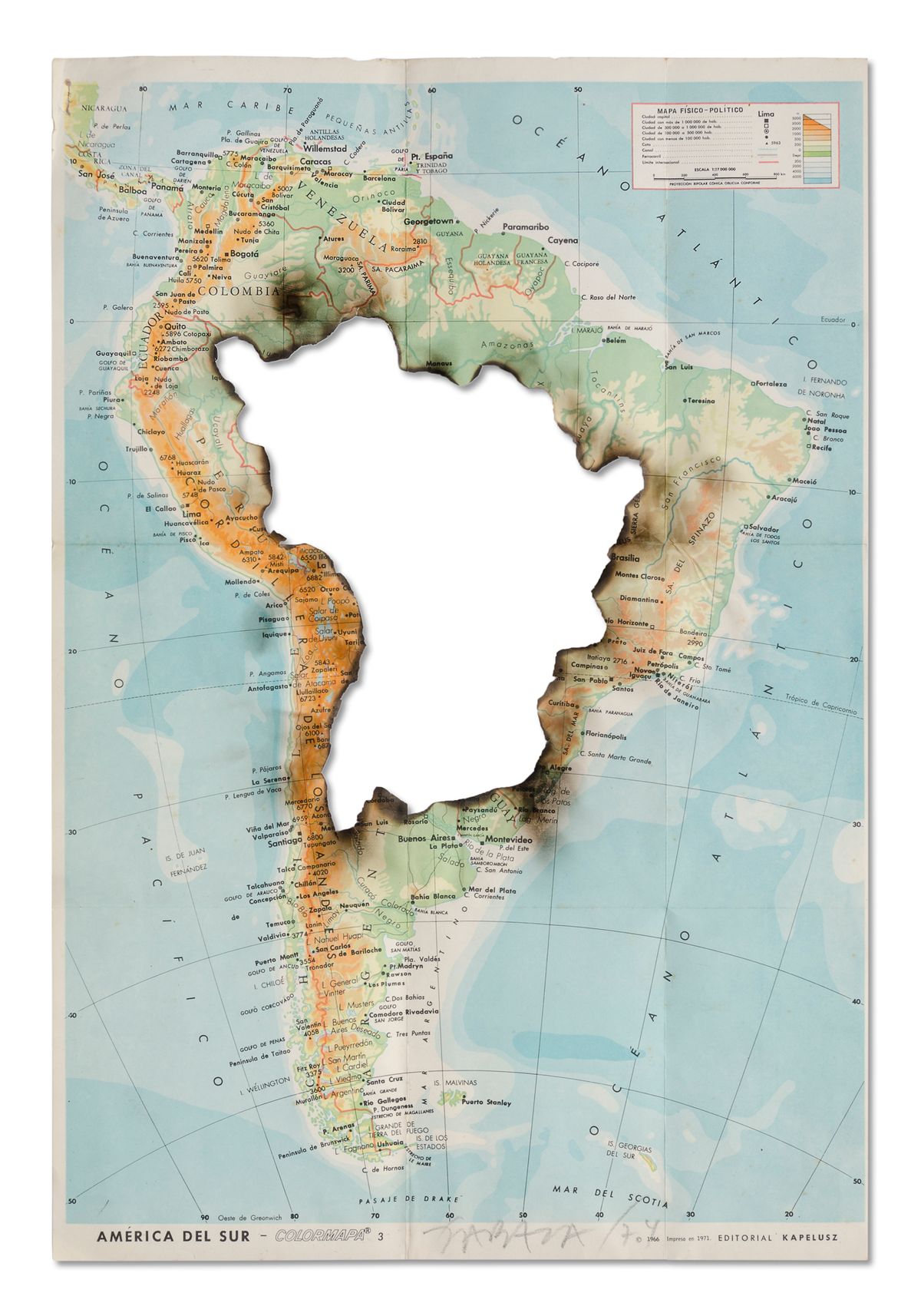

Their work was provocative then, and still looks that way, even removed from its original context (often a problem in shows of politically urgent art). With Lygia Pape—for Gonzalez, the most significant figure of each period noted here—artists such as Glauber Rocha, Lina Bo Bardi, Leon Ferrari, Cildo Meireles, Juan Downey, Alfredo Jaar, Anna Bella Geiger, Eugenio Espinoza and Cecilia Vicuña (to name a few) turned away from the Modernist abstraction of 1960s New Objectivity to champion “de-schooling” and disseminate regional values by way of alternative cartography, mail art, sculpture (including wearable works), drawing, painting, installation, video, photography and performance. (Paulo Freire’s Model of Banking Education is especially telling.)

The show, both ideological and formal, is vast in its reach. It could have been claustrophobic. Instead, Gonzalez has made the most of limited space to present an exhibition that’s as thoughtful, pointed and passionately conceived as the artists—and their audiences—deserve.