Customs figures just released show what may be the first impact of Brexit on the UK’s art market, but they also reveal that global British exports proved fairly robust in 2017.

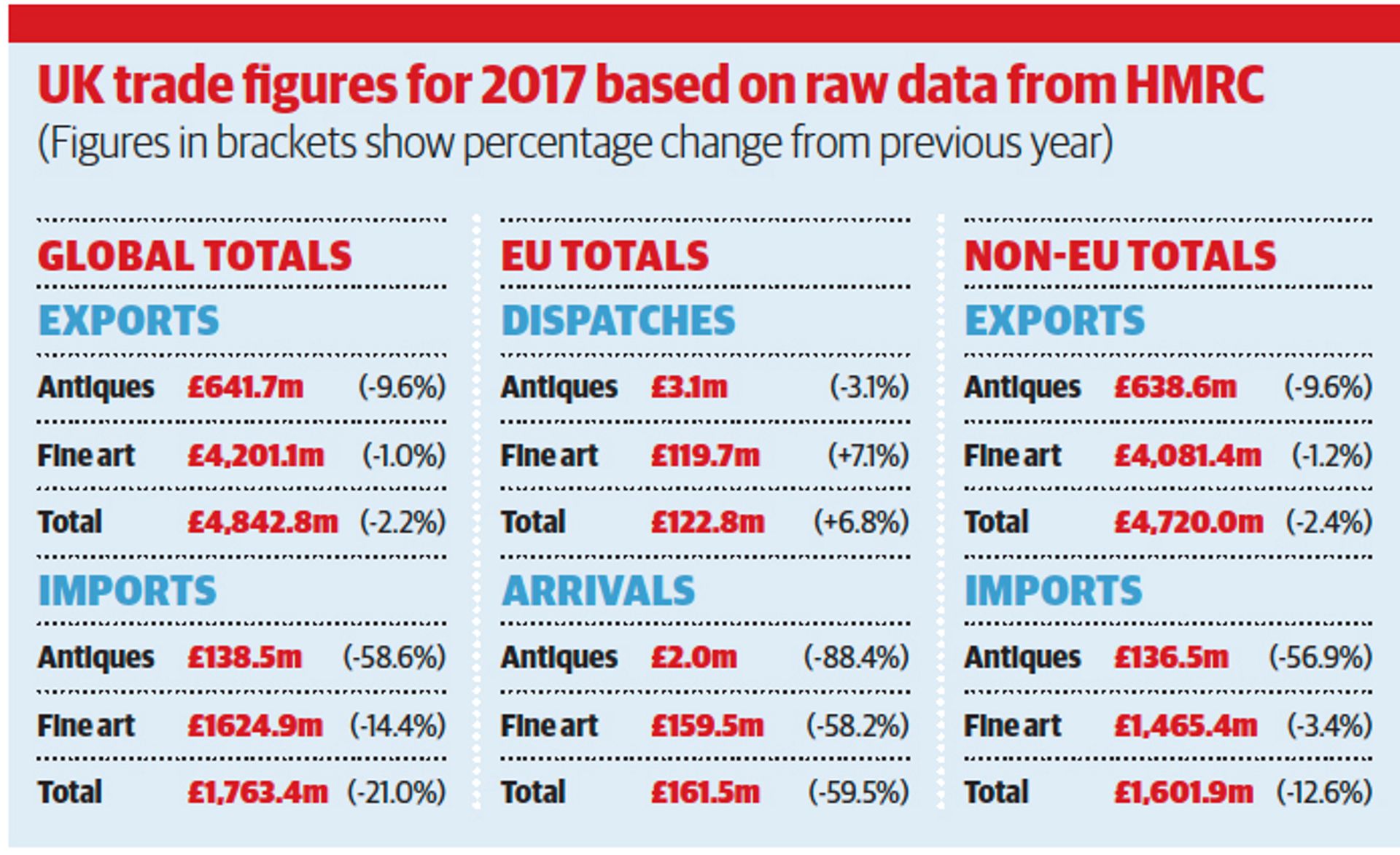

Export figures reveal an overall decline of just 2.2% to £4.84bn, while imports dropped by a much larger 21% at £1.76bn. But drill down further into the data and a more complex picture emerges.

Bearing in mind that the UK remains subject to European Union rules for the time being, a significant fall in import traffic from its main EU trading partners—down almost 60% year-on-year—could be the result of simple reluctance to send art and antiques there for sale following the Brexit referendum, but the weakness of sterling, especially in the first half of 2017, might also be to blame.

The UK’s trade with the world’s leading markets has proved stable in 2017.

In 2016 a general decline in the global art market masked any effect that might have resulted from the UK’s decision to leave the EU.

The UK’s trade with the world’s leading markets has proved stable in 2017 TAN

Globally, the relative health of the fine art market, with prices at the top end climbing even as the middle market stagnates somewhat, has compensated for a serious blow to the international antiques market, with UK imports down nearly 60%. Prices for top-end fine art appear to be increasing still but the rest of the market, whether for art or antiques, is fairly static. This would help to explain the growing gulf between fine art and antiques.

It is important to remember that these figures measure the value of goods crossing UK borders rather than sales so can include, for example, works of art being moved for display, but they do reflect market trends and spheres of influence.

Intrastat, the alternative system to customs for collecting and processing statistics on goods moved within the single market of the EU, allows countries to set annual value thresholds below which businesses do not have to file reports on goods moved across internal borders. These vary from country to country and are generally quite high, so figures for EU Arrivals and Dispatches, as they are known, do not cover anything like the entire value of goods moved within this sphere, which is why the totals seem so low comparatively.

However, they do provide useful information on trends, as can be seen in the 2017 collapse of picture arrivals in the UK from the Netherlands, home of the Tefaf Maastricht fair. The 2016 total was £127.7m (a rise of 47% on 2015), but in 2017 this fell to £9.9m. Because correlation does not mean causation it is not possible to point conclusively to Brexit as the determining factor but it must give pause for thought.

If not the result of anti-Brexit feeling, the chief barrier to UK imports is likely to have been the weakness of sterling, notably in the first half of 2017, during which time it would have been a relatively unattractive destination for anyone sending their art and antiques to market.

While the overall picture for sterling has been a steady recovery in 2017 from a January average of $1.23 to the pound to a December average of $1.34, the annual average held at $1.28, a match for the six months following the Brexit vote in 2016.

Despite this, the UK’s trading relationships with the world’s leading markets have proved stable in 2017. A breakdown of imports from the US (the UK’s most important trading partner) by month does not show any specific trend towards recovery to reflect the rise of sterling as the year progresses and appears more to reflect the seasonal ups and downs of the market.

Taken in the round, along with healthy imports of pictures from the world’s other largest entrepots [key market hubs] Switzerland and Hong Kong, it would appear that, in fine art at least, the UK continues to enjoy a good relationship with its chief global trading partners regardless of political upheaval, while the weaker currency will have had some impact on values in what remains a rather stagnant if fairly stable market.

Looking at the market over the two-year term, the decline is more pronounced. UK global exports over this period fell 15.5% (after a previous rise of 28.4% on 2014), while global imports dropped 50%, albeit after a 15.4% rise on 2014 totals. Results over the past five years indicate a fairly steady decline in imports but a more robust position for exports.

As usual, anomalies appear among the figures, which indicate extraordinary movements in the market. In the past these have included significant transactions by some of the world’s wealthiest individuals as they add to their collections and stock new museums with art. Bermuda is not usually among the UK’s most valuable trading partners for art, but in 2017 came fifth in importance, after the US, Switzerland, Hong Kong and China, for UK exports of pictures, accounting for £80.5m.

China recorded the biggest uplift on this front, topping a total of £25.5m worth of pictures for the UK in 2016 with a figure of £115.9m in 2017, a rise of more than 350%.

Meanwhile Russia’s influence on the UK market has declined significantly, with UK exports of pictures there falling by nearly 40% to £27.9m.

Frieze Week sales—usually a bellwether of market health in London—remained healthy, with Christie’s posting £134m compared with the £90m in 2016 for Post-War and Contemporary art, but some reports noted a little less confidence than the year before at the fairs despite some notable highlights.

British Art Market Federation chairman Anthony Browne said: “These figures underline the fact that London’s position as a global art market hub rests on its role as one of the world’s leading entrepots. They also demonstrate the UK market’s ability to operate on a global scale whether it is part of the European Union or not.”