Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933) and his wife Emilia (b. 1945) are the most internationally famous Russian artists, with a long, successful career together. London has just seen their work in the Tate Modern exhibition, Not Everyone Will be Taken into the Future, and the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington is showing The Utopian Projects, with 22 of their installation models with music, lighting and texts, until 29 April.

Ilya is the one with the training and career in visual arts; Emilia is a musician, the organiser, the person with her feet on the ground, she admits—but also the pilot of their extraordinary peripatetic project, The Ship of Tolerance, born in 2004 and taken around the world to show young children a world of empathy, artistic fun and joy.

She wishes they were not so identified with Ilya’s critiques of the Soviet system and emphasises that his work applies to situations everywhere, but is deeply rooted in the Russian seam of utopianism. His meticulous drawings for the Manas installation about an imaginary paradisiacal city are in the tradition of the Paper Architecture of the post-revolutionary period, never intended to be built but to inspire. To this imaginary world of constructions, he adds his stories that are a lot like fairy tales (and fairy tales are not always nice). The years of illustrating children’s books cannot fail to be woven into his imagination, although that side of his career is played down because it earned him his livelihood in the Soviet system. Metaphor and symbolism are there in abundance.

For years now, the couple have been living by the water on Long Island, in a handsome grey and white clapboard house with a large studio next door. The world that made Ilya and Emilia Kabakov—and that they have made of it—is there too, in dozens of meticulous wooden models of their installations and exhibitions over the years.

We went there to talk to Emilia Kabakov about their aims and lives as artists.

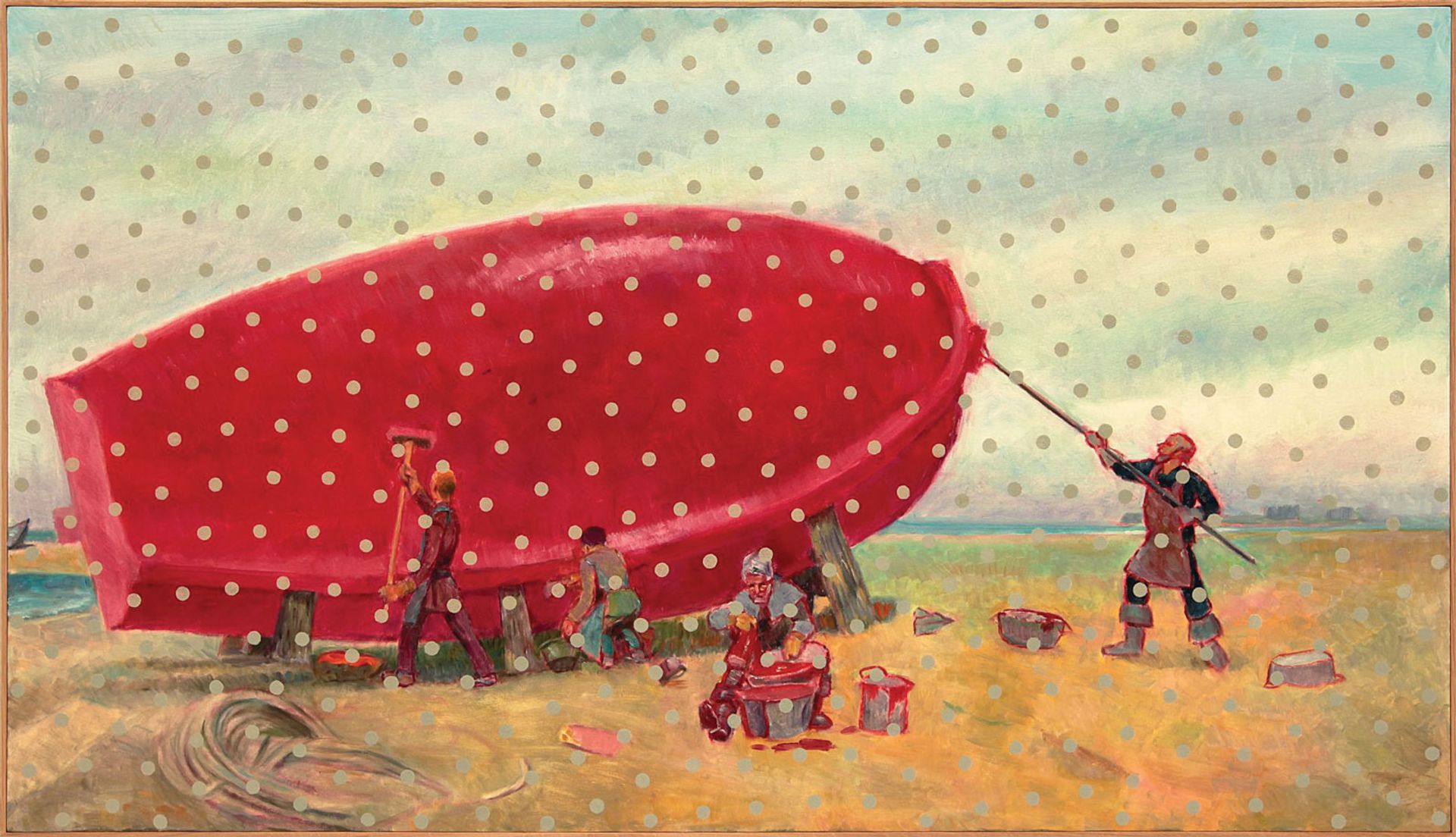

They are Painting the Boat (2015) is one of The Six Paintings about the Temporary Loss of Eyesight Ilya & Emilia Kabakov; courtesy of the artists and Pace Gallery

The Art Newspaper: I would like to begin with Ilya Kabakov’s famous 1985 installation, The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment. Am I right that this is about the power of the mind to transport you anywhere, but also about the dual reality of the USSR, which was a very restricted life for its citizens, but with huge aspirations and achievements?

Emilia Kabakov: Life is about desire and fear, so we want something, but we’re afraid of it at the same time. This union is the desire for paradise, but paradise on earth, which is different from religion. The results of trying to achieve this were something that brought fear, so then the next level of desire arrived—the desire to escape, so the man made this device that helped him to escape the world. Of course, it’s also the desire to escape from solitude; it’s not only the Soviet Union. It can be much more broadly interpreted because we always try to escape from reality. This installation is the concentration of escapism.

We in the West tended to see the USSR in terms of its limitations on freedom, and as a threat to ourselves. How did you live in it and how did it affect you as artists?

Ilya created a society, a very close circle of friends. They created paradise in hell, as it were, so they not only survived but they managed to create something completely different from everything else. But obviously, that was possible only under suppression; only inside hell can paradise exist.

There is the paradox.

It’s a paradox, but obviously if we expand this notion, then we see, for example, that the Soviet Union was considered a hell, America a paradise, and the world was divided between them. Then the Soviet Union fell apart and we lost the balance. Now we don’t know where’s hell, where’s paradise.

It seems to me that humankind is dramatically poorer for the failure of the dream of creating paradise on earth. Now that the whole ideological ecology is different, has that made the creation of art more difficult?

When hell broke down, paradise obviously broke down too. Some [Russian] artists were able to adjust and say to themselves: “What is lacking in my art in order to become international?” But some were unable, and the easiest way out was to say: “They don’t like me because I’m Russian.” Or: “They don’t like me because I’m a genius. I’ll stay in my country and do what I always do.”

You and Ilya have formed a unity as artists since 1989. What do you think are the most pressing things to be addressed in your art today?

First, we would really like people to stop thinking about us as Russian artists of the Soviet period, all about the communal apartment, the suffering of the Soviet people, and so on, because the topics are much wider. It’s the suffering of people all around the world. People are afraid to talk about government, about politics. If they do, they get shut up immediately by somebody. Our communal kitchen today is Facebook: you say something wrong and everybody jumps on you and starts screaming. The whole world has become a communal kitchen.

You are known as conceptual artists, but Ilya was highly esteemed also as an illustrator. This tends to be ignored because it’s what gained him membership of the Soviet Union of Artists—but Russia had, and still has, very good illustrators. Could you tell me how much this training in putting images with words has formed him as a “fine” artist?

I wouldn’t say his use of language and images in combination comes from illustration; that’s a big mistake. Jean-Christophe Ammann [the Swiss curator] once said that with Russian artists, visuality is not their strong point, they only have language. Ilya is a conceptual artist first and foremost. If you look at his illustrations, they’re not exactly about the story. But did he use his skills as an illustrator? Yes, he did. He can paint anything. He has a tendency to say: “I’m a bad artist, I can’t paint, I can’t draw.” I don't know why, because he can do Baroque, he can do contemporary—anything that comes into his mind. The difference is that, though he can do Baroque, it’s going to be a concept of Baroque painting, not a copy. You have to come with a concept.

You left the USSR first, didn’t you?

My father was from Poland and my parents wanted to emigrate. When they tried, in 1957, they were arrested. I was 11 years old. They spent quite some time in jail, which influenced the rest of my life mentally, physically, emotionally. I was a professional musician, playing concerts. When I came to the West in 1973, I taught, but I don’t like teaching, I like performing. I began working with contemporary artists, American, Polish, Russian, and I was advising a company and private people, and then Ilya came. He’s my mother’s second cousin; I’ve known him since I was born.

That was 1987. Did he jump or was he pushed?

No, he left in the usual manner for Russian artists. He was invited by the Austrians for a six-month residency and just didn’t go back. We met when he was in France. I went to see him, because our love affair had started much earlier, in Zurich, and then he came to the US for an exhibition and we became a team.

You must have been a great help to him because you understood how the art world worked here.

I did and I didn’t, because I had been protected by the people I was working with; they were very rich, and Van Gogh is different from contemporary art.

When the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg chose for the first time to exhibit a living Russian artist, in 2004, it was you two. Was this because you had an established reputation in the West, or because they were re-evaluating the old Soviet Union and you were an interesting exemplification of it?

You need to ask [the Hermitage’s] director, Mikhail Piotrovsky.

What did they say about you in the speeches at the opening?

Great Russian artists.

How were you received?

Very well. We couldn’t get to the front of the museum; there were thousands of people just standing there.

This January, Russian law reclassified art that is younger than 50 years since its creation as contemporary art; before that it was called luxury goods. I know that contemporary art is still considered there to be less important than classical art, but do you think this attitude is changing?

With younger people, yes, but still not so many. The 2016 Jan Fabre exhibition at the Hermitage wasn’t understood at all and there was a huge scandal.

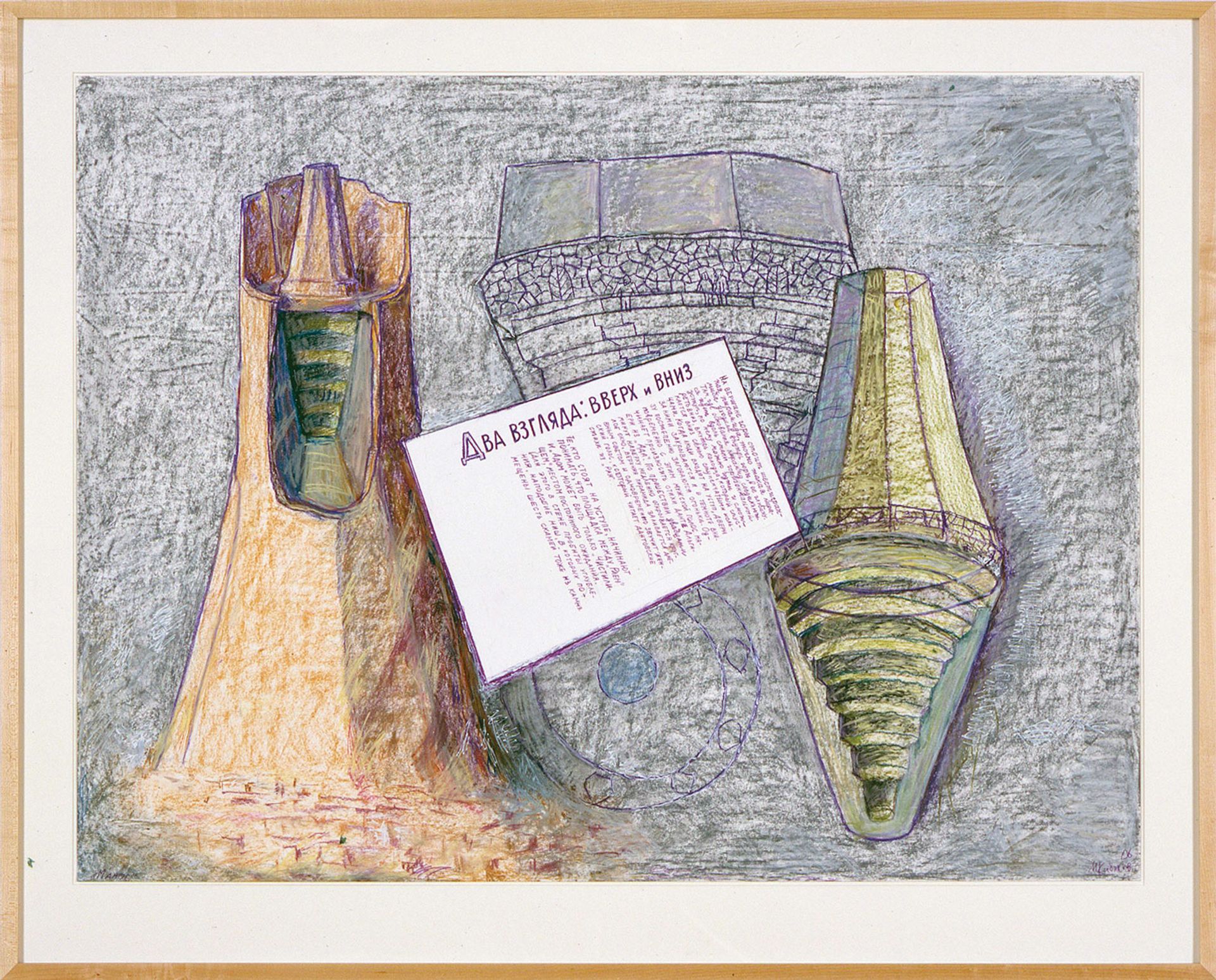

A work from the Manas series (2006) Ilya & Emilia Kabakov; courtesy of the artists and Pace Gallery

Your Ship of Tolerance has travelled the world. When did this start?

When we created it the first time in Egypt, at Siwa, in 2005. We said, let’s do something with the children. We had local children, but also from Manchester. They didn't have a common language, but they started playing soccer, running around, exchanging presents. They don’t need a language.

Under tens?

Yes. I started thinking that maybe we could do something much more important, so our next project was in Venice. We went to the worst schools there and discovered that racism is not only in America, it’s everywhere. So we continued and the project got bigger. For example, we added a concert.

How many children are involved in one of your ship projects?

In New York, in 2013, 100 schools participated with the help of the philanthropist Agnes Gund. She just gave me money—I didn't even ask her. With her foundation, she sent 100 young artists to work with the children. Fantastic: talk about tolerance; make the drawings; then we decorate the whole of Brooklyn and New York with them. If you went in a taxi, you saw a video with the ship. We brought the children to The Ship of Tolerance. They rode the carousel for free. They got presents. They were playing, dancing—it was a festivity.

Do you always have the ship?

We build a ship every time. If somebody wants to keep it, we’ll leave it there, but we never sell it. We keep some of the drawings and leave the others if the schools or community centres want to sell them to get money for the programme. If we exhibit the drawings, we send money for scholarships.

Where is the next ship going to be?

Rostock in Germany, at the request of German government, because there is a lot of tension right now with refugees. There’s already been work going on there for a year with the refugee centres. I’ve been talking to children on the internet about tolerance and they are making drawings. There are teachers and special people who talk to them about it, and I will put all of them together; I will put mothers together with their children when they draw so that they communicate. We’re going to have a very big celebration at the opening on 19 May. At the same time, we are bringing 11 kids for the concert from different countries—a wonderful boy from Armenia who plays the duduk [a reed instrument], and one from Georgia and another from Iraq. I am bringing the ship to London on 17 September; I just need to raise a bit more money.

For Chicago this year, you are working with Theaster Gates, who is both an artist and social activist.

When I first met him, he jumped on me like I’m his lost mother or sister and started kissing me. We’ve decided we’re going to build the ship probably on his premises. We’re going to give a concert, and we’ll work together to pull communities together. I was completely smitten by his library—I like his mind, it’s so expansive.

Is the thrust of your work now to try to emphasise a common humanity?

The Ship of Tolerance is mostly a social project, although it is an art project as well, but with our art we have been working for a long time with utopia, with fantasy, with dreams, as with [our installation] Manas, one of the drawings of which has been made into a print for you. Manas is a paradise. It’s a little place in the world that’s like Shangri-la, which you can reach by travelling in your mind.

Do you think it is a moral duty of art today to engage with social problems?

I don’t think art has any moral duty. Art is art. But as an artist, it’s your choice what you do, and I think it’s very important you don’t do anything to publicise yourself, but because you see results.