Sonia Boyce’s exhibition at the Manchester Art Gallery (MAG) gained an unexpected notoriety before it had even opened. In late January, the gallery took down one of its best-known works, Hylas and the Nymphs (1896) by John William Waterhouse, as part of a series of activities in Boyce’s evening “takeover”, a regular event at the gallery. The evening would be the basis of her new six-screen film and wallpaper installation Six Acts (2018). But the painting’s removal became isolated from the evening’s other moments and a row about censorship erupted, largely stripped of any context.

The background to the project is complicated. Invited to exhibit at the gallery last year, Boyce instigated several discussions on her visits to the gallery over a period of months—conversations that involved curators, gallery assistants, volunteers, cleaners. Boyce saw her role as being “to facilitate the discussions, because I was trying to understand what was emerging from this particular context”.

As the conversations developed, and the group swelled in number, two works became a particular focus. The first was Othello, the Moor of Venice (1826) by James Northcote, a painting of the black actor Ira Aldridge, the painting that “started the collection as a whole”, Boyce says. “I started to think that it would be really interesting to have somebody—and I thought very specifically of a performance artist called Lasana Shabazz—to work with this painting as a starting point,” Boyce says.

The other work was Hylas and the Nymphs, in which Waterhouse depicts the moment in the Greek myth where the young man Hylas, Heracles’s lover, was abducted by water nymphs. It features several young, nude women enticing Hylas into their spring. In the discussions, Boyce noted that the Waterhouse prompted “a discomfort among the staff themselves, not only the conversations that they’ve been having publicly with visitors to the gallery, but about an overarching narrative: first, a sense of the idealised female form, but also the female figure as the embodiment of death or something deathly, which is a very old trope”. Hylas’s sexuality was also significant.

“Whether people will be too troubled by it or whether people will enjoy how they’re being troubled, I can’t predict.”

After four sessions, Boyce says she told the growing group that “because of this question of gender representation and the way in which the conversation was going, we need to not be binary about how we’re thinking around questions of gender and masculinity and femininity, that we need to complicate some of those questions, because there’s been a lot of discussion about non-binary questions around representation”. She knew that there was a “very dynamic drag scene” near the museum and made contact with a group called The Family Gorgeous. They joined the discussions, as did Shabazz.

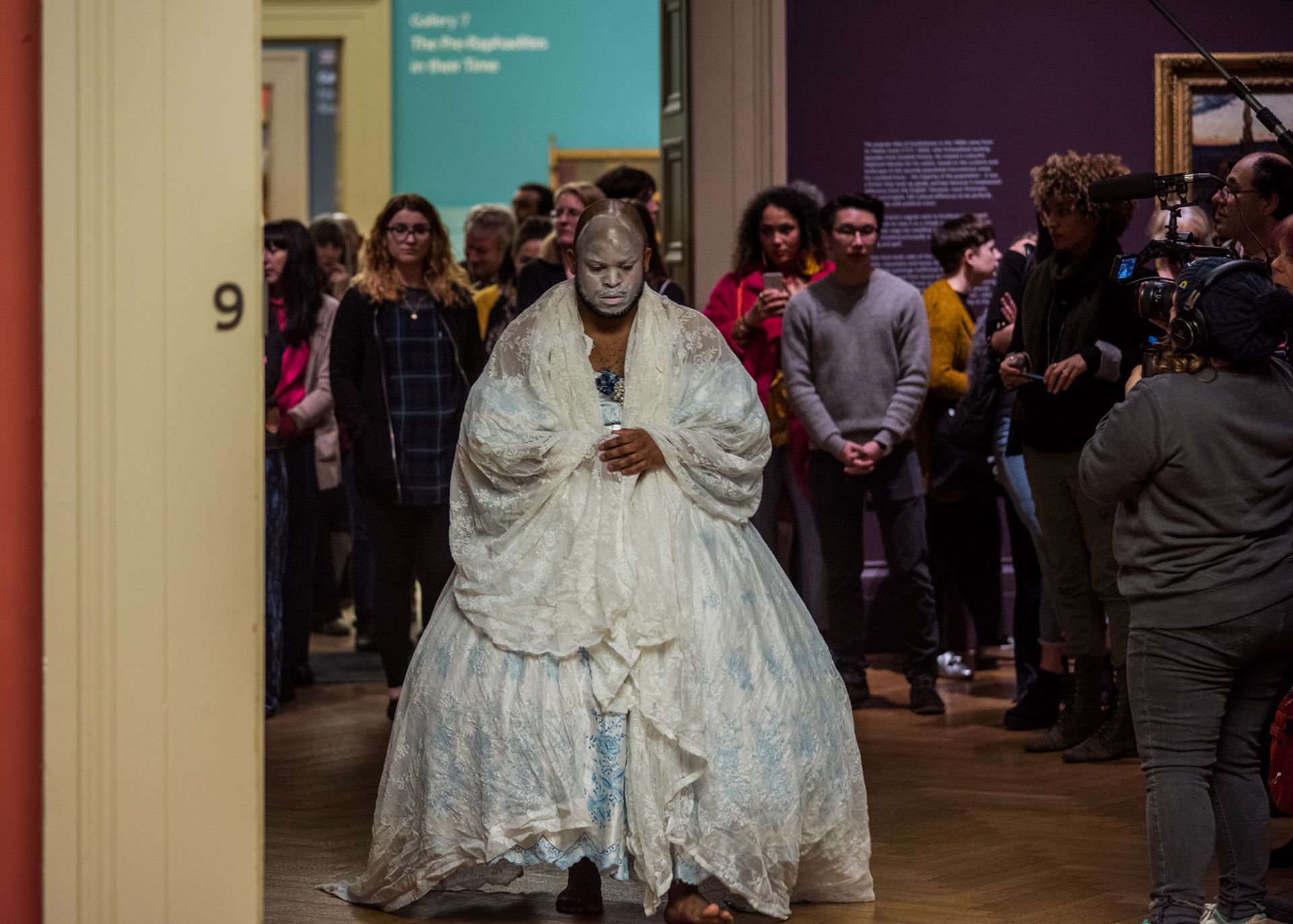

The final evening event, was divided into six performances. In one, Shabazz played with the character of Aldridge, wearing a white dress and “whiting up” as Aldridge would have had to when adopting Shakespearean roles beyond Othello; in others, The Family Gorgeous responded to other works in the collection. Boyce stresses that “there was no script, we didn’t know what they were going to do, we didn’t know what they were going to look like – the performers really took on board quite a lot from the discussions, and worked really hard and sensitively to think about what emerged from those conversations that they wanted to take up and comment on and have an opinion about”.

Cheddar Gorgeous performance during Sonia Boyce's gallery "takeover" event in January 2018 at Manchester Art Gallery Photo: Andrew Books

The decision to take down Hylas and the Nymphs emerged from the discussions. “It wasn’t unilateral,” Boyce says. “There was a lot of ambivalence, but the consensus was that as one of the acts that would take place on the night of the takeover, this painting should come down.” She adds: “My role is to say: ‘If that’s what you want to do, let’s make that happen.’” The work was taken down and visitors were invited to write their comments where the painting had hung.

The takeover programme had never attracted much attention in the press, and so there was “no anticipation that this was going to have such far-reaching impact, or even be taken to the media”, Boyce says. But the artist Michael Browne, famous for his paintings of Manchester United footballers, saw the event, and posted on Twitter that it culminated in “the permanent removal of Pre-Raphaelite painting Hylas and the Nymphs, because the female staff view it as negative, bad taste, out of date. Is artists [sic] freedom in danger?”

This, says Boyce, “is how things in some ways unravelled and spiralled”. News reports appeared and there was a flurry of condemnation, and cries of censorship, including in a piece by the Guardian art critic Jonathan Jones, who neglected to mention Boyce, and wrote of “new puritans” returning us to “an era of repression and hypocrisy” and detected “the spectre of an oppressive past wearing new clothes”. Elsewhere, the event was seen as a publicity stunt. “The idea that it was intentionally a stunt to draw attention to the museum or to myself was the furthest thing from [our minds],” Boyce says.

She adds that “the question of censorship is in there, but if you shout censorship from the off, then you can only go two ways—it gets polarised just by that term”. There is a counter-argument that it is those crying censorship who are the censors, that they are shutting down new responses to canonical works by artists and performers exploring non-normative and non-binary representations of gender and sexuality.

Lasana Shabazz performance during Sonia Boyce's gallery "takeover" event in January 2018 at Manchester Art Gallery Photo: Andrew Books

“The question at the heart of all of this is the question of power,” Boyce says, “and who’s given legitimacy or takes up legitimacy to have an opinion. And really, a lot of the discussions we were having were about an invisible sense of who has the power to frame certain narratives.” She suggests that the job of curators and artists is “to have an opinion, to make a judgement; judgement is the cornerstone of what we do”.

Is she relieved now that the Six Acts film installation, including that contested removal, is complete, that the public can see it in its intended context and the debate can be refreshed? “[Visitors] will see something that they’re not expecting to see from what’s been created from that event. [The film Six Acts] is very lush. It’s very, very funny, it’s very troublesome; whether people will be too troubled by it or whether people will enjoy how they’re being troubled, I can’t predict.”

The furore around Hylas and the Nymphs has distracted from the importance of Boyce’s exhibition. It is only part retrospective: the drawings with which she established her reputation in the 1980s, like Missionary Position II (1985) in the Tate Collection, do not feature. Instead the show focuses on her “multi-sensory” practice from the 1990s onwards. She insists that her art is “still rooted in that early work, but has taken on a different shape and a different kind of trajectory”. Where Boyce was front and centre in her 1980s work, her collaborators are now the protagonists. She sets up the parameters and leaves it open for them to perform, even allowing her film crew to capture the event as they see fit. She then edits the material together.

Boyce says that “dialogue is a central theme throughout the work that I’ve done since the 1990s”, and one of its most potent manifestations is through sound. For You, Only You (2007) in the MAG show takes a choral Renaissance score and reworks it with the avant-garde sound artist Mikhail Karikis and the choral group Alamire, with references to both Dada and jazz scat improvisation. These different cultural idioms fuse to form “a sonic history in the work that I make”, she says, entangling different cultural identities.

A still from Sonia Boyce's Crop Over (2007) film Collection Barbados Museum and Historical Society

This is visible, too, in Crop Over (2007), a film which begins at Harewood House in Yorkshire, built on wealth generated through Caribbean plantations and slave labour, and explores the relationship between the UK the titular harvest festival in Barbados. “Musically as well as symbolically, in that harvest festival, there are African traditions, there are Scottish traditions, there are things that emerge directly from being in the Caribbean and in the Americas, that all collide,” Boyce says.

Fundamentally, Boyce’s art “is about people”, she says, “and though some people may feel alienated by some of the subject matter, I am very keen on bringing them in and getting people to have different, complex relationships with the work.” The Hylas and the Nymphs saga might have kicked off her MAG show with a shriller debate than she intended, but the attention it brought might, for some at least, prompt the more considered response she seeks.