Tacita Dean’s approach was always more reticent and subtly atmospheric than her throat-grabbing YBA contemporaries. Currently based in Berlin and Los Angeles, Dean is best known for her poetic and distinctive films which—whether they present David Hockney smoking, two pears fermenting in schnapps or a solar eclipse—are as much about time passing and the material of film itself. FILM (2011), the first moving image commission for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, was a silent celebration of the masterful techniques of analogue film-making, and Dean continues to be a passionate and dedicated campaigner for the continued production and use of chemical film in the face of digitalisation.

She has also always worked in other media, including making large drawings in chalk on blackboard, paintings on postcards, sound works, photographs and photogravures. Now, the full scope and richness of Dean’s work is to be revealed in three exhibitions, which mark a unique collaboration between three London museums. In its first exhibition devoted to the moving image, the National Portrait Gallery is showing her film portraits; the Royal Academy of Arts is inaugurating its new galleries in Burlington Gardens by exploring Dean’s wide use of landscape; and at the National Gallery, Dean is curating an exhibition of both historical and contemporary works, as well as showing four of her own films devoted to the genre of still life.

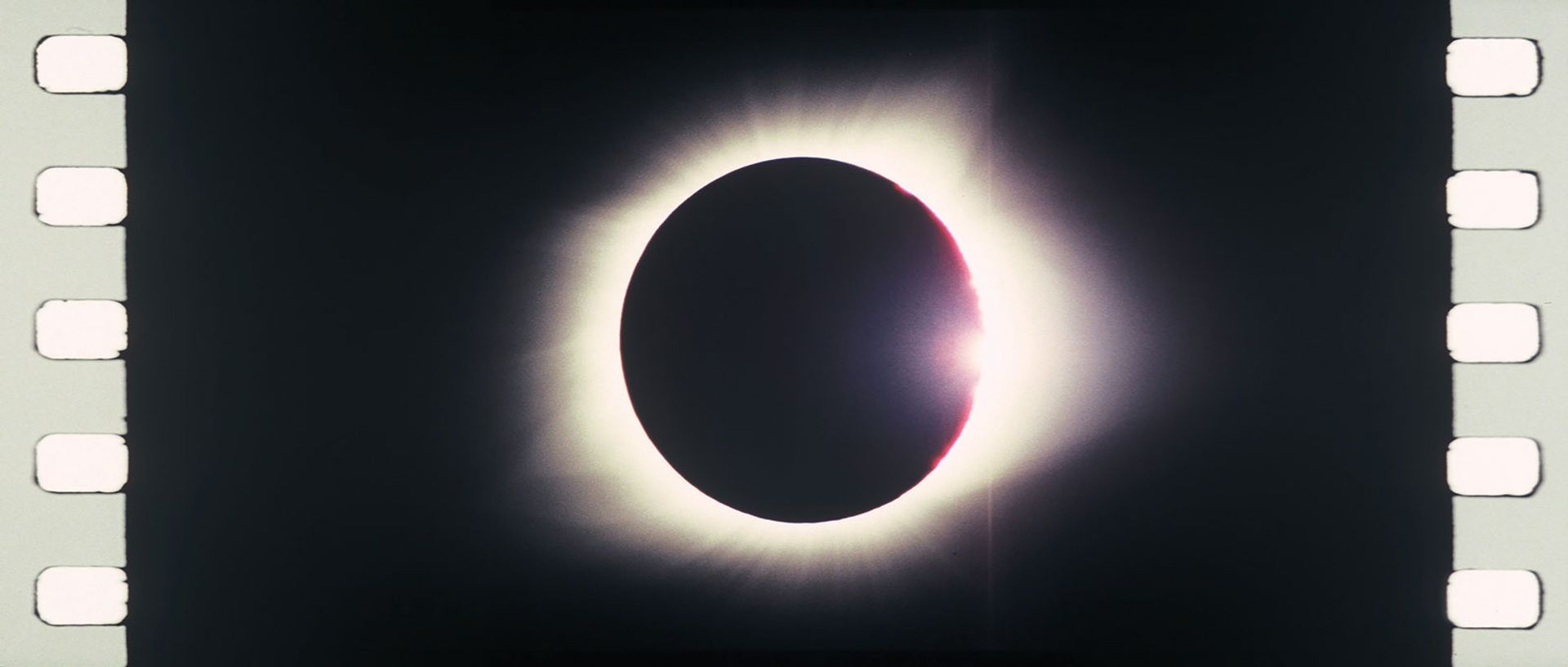

Film still (detail) from Tacita Dean’s 35mm anamorphic film Antigone (2018), made for the inaugural show at the Royal Academy’s new galleries in Burlington Gardens. The artist, Frith Street Gallery, London and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris

The Art Newspaper: How did it come about that your shows across three institutions have been divided according to genre?

Tacita Dean: It began with simultaneous separate invitations from Tim Marlow [the artistic director of the Royal Academy] and Nick Cullinan [the director of the National Portrait Gallery], and I thought I should try and join the shows together. Nick had the idea of the genres, and to bring in the National Gallery for still life. I have made new work for all three of the exhibitions but at the Royal Academy 75% of the show is new, whereas the other two shows are more pre-existing work. At the National Gallery I’m curating with their collection, adding a few works by contemporary artists and also works from other national collections, and bringing in four of my films.

Do these exhibitions question traditional ideas of landscape, still life and portraiture?

I’ve never thought in genres. To some extent, it’s a synthetic idea imposed on my work but actually it’s been the perfect device for these three exhibitions. I didn’t even think of my portrait films as portraits. Other people imposed the idea [of portraiture]. What is or isn’t a still life, especially, can cross categories. My film Merce Cunningham performs STILLNESS, at the National Portrait Gallery, is a possible still life, in a way; and lots of works at the National Gallery—including the new diptych film, Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting, of Henry Moore’s flints—are still life in the landscape. These exhibitions are also about challenging the hierarchies of painting, because those genres are so associated with painting, and it’s nice to subvert that by using mediums including film or drawings on slate that aren’t strictly within these traditional ideas. My round stone collection that I’m showing at the RA has a very specific relationship to the idea of the landscape.

Antigone, the new film at the RA, mixes different places, objects, people and events—including the 2017 solar eclipse—sometimes in a single frame.

It’s more than a landscape, it’s a portrait too, and the most ambitious thing I have ever done. It’s hard to describe: to some extent it’s a collage and it’s mad in its scope. Antigone is my older sister’s name, so it’s a word that I’ve been carrying through my life. Even from very early on my first drawings were about the name Antigone, and I also took the idea to the Sundance Screenwriters Lab in 1997, so it has been my unmade project for 20 years. It’s now a diptych, so that it can never be shown theatrically. It can’t be a feature film.

Tacita Dean photographed in her studio In Los Angeles, October 2015 Jim McHugh / Los Angeles

In Antigone you’ve used the same risky analogue film-masking techniques that you first developed in FILM at Tate Modern.

It’s about blindness, to a certain extent: the solar eclipse being the ultimate natural blindness, and Oedipus’s blindness and then the blindness of the whole process of masking the film. This is the first time I’ve done something as terrifying as taking unprocessed film across the Atlantic to film half a frame in one location and the other half in another. For example, I filmed a quoit in Cornwall in February and then in August filmed the solar eclipse in Wyoming on the other half of the frame with no backup. But it came out in the most beautiful way. I also did it with [the poet and writer] Anne Carson and [the actor] Stephen Dillane, with him asking questions in Cornwall and her answering them in Thebes, Illinois.

You’ve also used these methods in another new film for the National Portrait Gallery, which responds to its miniature collection by making a film in miniature.

I was very interested in doing something outside the exhibition space. They have a very beautiful collection of miniatures and I thought, OK, I’m going to try and make a miniature, which is a strangely discredited sub-genre. Miniatures have to be about the face, so not my usual approach to making a portrait. I filmed three actors—David Warner, Stephen Dillane and Ben Whishaw—at different times but using masking so they are all inside one film frame, sharing the same photochemical space. There’s nothing more intimate than sharing the same film frame. It was shot on 35mm cinemascope and then reduced to 16mm so that it could be shown as a miniature. It’s called His Picture in Little, which is taken from Hamlet.

And all three actors have played Hamlet, too.

Yes, but that’s an aside for me. They don’t say anything, they just are. Asking an actor not to do anything is really difficult, so I drew David and Stephen—that was what they could understand as sitting for a portrait, even though it was on film. The drawings were awful but that action gave them the relationship to a portrait.

You’ve made films of an extraordinary range of people, including Merce Cunningham, Cy Twombly, David Hockney, Julie Mehretu, Leo Steinberg. How do you choose who to portray?

Each one came out of a different circumstance. It’s not like I’m prowling around looking for old men, though it might look like it. Everything is always very fortuitous, that’s why I believe in contingency and chance. Things happen because they happen, and they seem to be more important later. It is very interesting to look at all those art historians and how they attribute everything to a deliberate act. It’s not like that—artists aren’t like that.

Everyone in your films looks remarkably unselfconscious and not as if they are being portrayed. How do you get them to look as if you aren’t there?

Creating situations where they lose that self-consciousness is a huge part of it, but to be honest, it is a lot to do with the editing and finding the moment. Of course, people are self-conscious. With Claes Oldenburg, we filmed him all day and it was only in the last 40 minutes that I realised we had a film. The only person who wasn’t self-conscious was David Hockney. He was such a pro—he can play the game.

The film His Picture in Little (2017) was inspired by the National Portrait Gallery’s collection of miniatures The artist, Frith Street Gallery, London and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris

As well as your work in 16mm and, more recently, 35mm film you are also known for being a passionate advocate and campaigner to save photochemical film from extinction.

Increasingly I make films that are more about the medium than they ever used to be, because the more it becomes threatened, the more I’m making work that can only be done on film. These films could not have existed in the digital universe because they are about the discipline and the eternal structure of film and how you expose blindly. Film is a medium, like chalk, like gouache: that’s how I talk about film to the cinema industry. When I started to talk about film being a medium and not a technology was when they got it. There’s no way the art world would say that you cannot use oil paint—people talk about me being an anachronism using film but oil paint is slightly older, no? We are still not in any safe place but, my God, the situation has shifted from 2012, when Kodak so nearly stopped. Now they have a laboratory in the UK, which is open and working.

It seems that drawing has also always underpinned your practice and has an especially close relationship to your films.

I don’t think my drawing was ever separate from my film-making: my first film, Eternal Womanly, was a 16mm animation of stop-frame drawings, similar to [the South African artist] William Kentridge’s method. In the chalk drawings on blackboard the idea of erasure is very consistent: I’ve been writing on the boards since the beginning, then rubbing it out, and that editing process has parallels with the films. I’ve also been painting little postcard images, finding different surfaces and ways to draw. Film is a very different way of working, but it’s so intensive, I also need to be back in the studio making things. The idea of the stuff of the medium is very important—the ability to make art from anything, from a clover to an old school slate. There have always been many, many mediums. I don’t use the word media any more—it means something different now.

Why are you not showing any seascapes?

The reason not to put any seascapes in my “scape” show at the RA is deliberate. In the UK, I am still seen as the artist who made works about the sea, and that’s where I stopped: I’ve been pickled in the sea work. So at the RA, even though I am looking at cloud-scape, tree-scape, mountain-scape, it’s all dry. I’m not denying the sea— I still love the sea—but I moved to landlocked Germany and I left the Island.

When I interviewed you in 2001, you had just decided to live in Berlin, saying you preferred to feel European. I imagine this feeling is stronger than ever, given the current climate.

I’ve started to call myself British European. We [Dean, her partner, the artist Mathew Hale, and her son, Rufus] are applying to become German. Hopefully we can then be dual British-German citizens. The slate drawings I’m showing at the RA have an element of melancholy, as their titles come from Shakespeare: the triptych is called Bless Our Europe and I’ve made a slate called Where England?, where the cloud just got smaller.

• Tacita Dean: Still Life, National Gallery, and Portrait, National Portrait Gallery, London, 15 March-28 May

• Tacita Dean: Landscape, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 19 May-12 August

Tacita Dean: Three Key Works

Tacita Dean: Disappearance at Sea, 1996 Tacita Dean; courtesy Frith Street Gallery; London and Marian Goodman Gallery; New York/Paris

Disappearance at Sea (1996)

The film that brought Dean to a wider audience. Inspired by the tragic story of amateur yachtsman Donald Crowhurst, who died in 1969 while participating in the first solo, non-stop, round-the-world yacht race, it cuts between a shot looking inwards to the bulb of St Abbs Head lighthouse beacon in Berwickshire and out to sea as the light fades. “That film was hugely important—it was a radical departure,” Dean says. “At that point I dropped the voiceover and I let the images take over. It was also the first time I ever looked at anamorphic lenses and started to play with the form.” The film is one of a number of works inspired by Crowhurst, who realised that he could not complete the race and faked his location while drifting fatally off course. These include a series of six chalk drawings on blackboard panels of tempestuous seas, annotated like a film storyboard, as well as a film, an artist’s book, and photographs that trace and chronicle Crowhurst’s wrecked trimaran, the Teignmouth Electron.

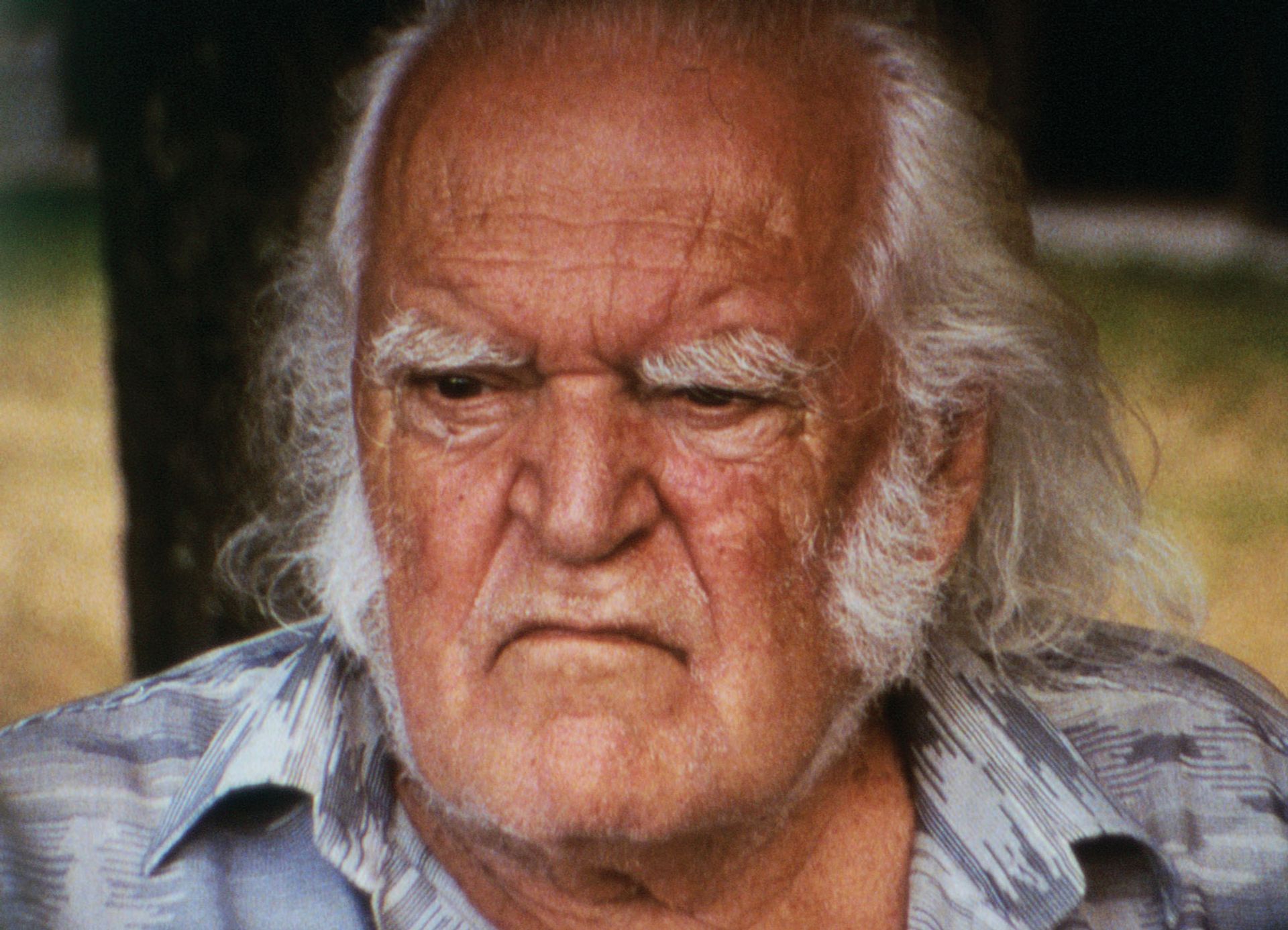

Mario Merz (2002) by Tacita Dean The artist, Frith Street Gallery, London and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris

Mario Merz (2002)

A film of the artist shortly before his death, sitting in a chair in Tuscany, holding a pine cone. “Mario was the first portrait film I made and there’s something about it that I really like. In my technical ineptitude I got all the exposures wrong, and it’s about how everything can go wrong, and how that can be right. Marisa [Merz, artist and Mario’s wife], trying to avoid the camera, walks right into the frame. There’s something very essential about that afternoon and that man. He didn't want any sound so I just got the sound of the cicada in the tree.”

Prisoner Pair (2008) by Tacita Dean The artist, Frith Street Gallery, London and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris

Prisoner Pair (2008)

“I’d seen somewhere they grow pears into bottles in trees; I’d always wanted to film the harvest. I had a show in Berlin and I wanted to make it about German subject matter—I thought I’d go and find the schnapps trees. But I missed the harvest, so I went to Alsace and bought a poire prisonnier from the French side [of the border] and one from the German. I buried them in the garden so they would have some patina, then filmed them, two pears, one French, one German, side by side, imprisoned in bottles of schnapps.”

Biography

Background Born in 1965, Dean grew up in Kent, the daughter of a judge and the granddaughter of Basil Dean, who founded Ealing Studios.

Education Between 1985 and 1988, Dean took a fine art degree at Falmouth School of Art in Cornwall. “I went down to Falmouth and fell in love. It was misty, there were fog horns and a Russian ship in the bay—it completely captured my imagination.” In 1992 she completed an MA in painting at the Slade School of Art. “I never studied film, I’ve always been in the painting department at school.”

Milestones In 1998 Dean was nominated for the Turner Prize for Disappearance at Sea, and in 2000 embarked on a one-year DAAD scholarship in Berlin, where she been based ever since. In 2001, aged 35, she was the youngest artist to have a solo show at Tate Britain. In 2006 she had a major retrospective at the Schaulager in Basel and won the Hugo Boss prize; an exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum followed in 2007. Other prestigious exhibitions include the Unilever Series at Tate Modern in 2011, Documenta 13 in 2012 and the Istanbul Biennial in 2016. Dean was elected a Royal Academician in 2008 and awarded the OBE in 2013.