Outsider, visionary, self-taught or maverick: choose a label if you must, but most of the exhibitors at this year’s Independent art fair (8-11 March), where plenty of work from these categories is on display at Spring Studios in New York, will call it simply rich, sensitive and meaningful work. “It seems completely reasonable to think of it as just another form of contemporary art,” says Matthew Higgs, the fair’s curatorial advisor and director of White Columns. By mid-afternoon his gallery had sold four portraits of bearded African-American men, each priced at $4,000, by Derrick Alexis Coard, an artist from the Bronx with developmental disabilities, who died just last year.

“For whatever reason, people love labels,” says Frank Maresca, of New York’s Ricco/Maresca, a first-time participant in the fair. “I’m a fan of labels at a supermarket.” His booth featured five architectural works on paper from Martín Ramírez, the recent subject of a retrospective at the ICA Los Angeles; priced between $30,000 and $110,000, two of them sold within the first hour of the preview on 8 March. The gallery also presented works by Leopold Strobl, who is associated with an art studio that emerged out of the Gugging Psychiatric Clinic, located outside of Vienna. More than 20 of his diminutive landscape abstractions, priced between $2,000 and $3,200, had found buyers. “Fear is like a hose that puts out the fire of creativity,” says Maresca. “These are people who don’t know the rules, so they’re not afraid to break rules.”

Leopold Strobl's Untitled (2014-109) (2014), among the suite of works by the artist presented by Ricco/Maresca at Independent Courtesy of Ricco/Maresca

How do galleries, not wanting to let biography take over or explain the works themselves, negotiate the complicated circumstances of such artists? “It’s really hard because I wish I didn’t have to talk about it at all,” says Claire Iltis, the associate director of the Philadelphia-based Fleisher/Ollman gallery, which regularly shows self-taught work alongside formally trained artists. The gallery’s booth includes colorfully executed pastels by Julian Martin, an Australian artist who is also autistic, that straddle figuration and abstraction. Elsewhere are small interiors drawn in soot and saliva by the legendary James Castle, which hang shoulder-to-shoulder with a large canvas, also of an interior, by the Philadelphia painter Becky Suss. Iltis notes of the trend toward omnivorous groupings at the fair: “It’s what we’ve been trying to do forever.”

Aaron Birnbaum's Untitled-landscape (1975) drew comparisons to the work of Charles Burchfield at Kerry Schuss's stand at Independent Courtesy of Kerry Schuss

Dealer Kerry Schuss has pledged his booth to the painter Aaron Birnbaum and it is curated by the New York-based artist Matt Connors. A tailor who only truly received recognition as a folk artist at the age of 100, Birnbaum’s works romantically recall his childhood in Eastern Europe, eliciting comparisons to Milton Avery, Charles Burchfield and Grandma Moses. “This is a visionary of the first rank,” says the art critic Jerry Saltz, a long-time champion of outsider art (a label he describes as “ridiculous”). Schuss credits Saltz, his wife, the critic Roberta Smith, and Higgs with pushing outlier artists into the mainstream. The dealer adds: “When you bring something to Independent, if it’s good, it can fly.” One of the paintings, whose prices range from $8,000 to $10,000, had sold.

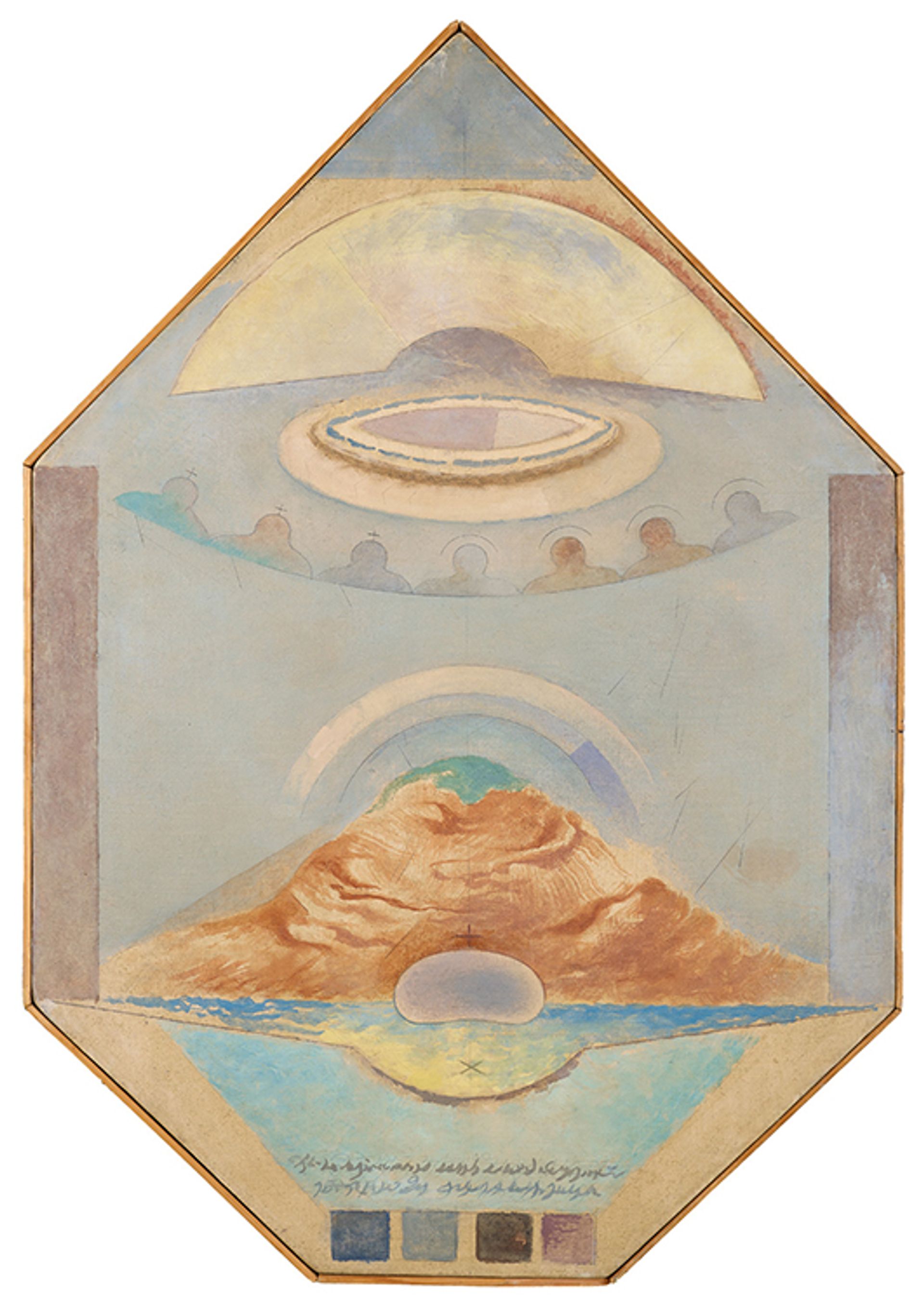

Like many others at the fair, Saltz thrilled to Alexandru Chira, the subject of Cologne’s Delmes & Zander’s booth, the late Romanian artist’s first solo presentation in the US. Chira’s diagrammatic drawings and canvases are intricate and obsessive elaborations on his creation of a meteorological monument in his small village in Transylvania, which is still being constructed, that will generate rain and rainbows—the artist’s response to a drought that plagued his village for an entire year. The gallery had sold five of the works, priced between €2,800 and €9,000.

Alexandru Chira's undated Study XVII, shown by Delmes & Zander at Independent Courtesy Delmes & Zander, Cologne

Collectors also found plenty to appreciate by more-established names in the contemporary field, especially where they overlapped with craft. David Kordansky, of Los Angeles, placed every last one of Ruby Neri’s suggestive ceramic works, at prices between $14,000 and $35,000, and Clearing sold out their booth of painted sculptures by Harold Ancart. Canada’s immersive presentation of ceramics by Elisabeth Kley was also fully spoken for.

Generally, the best parts of the fair are disheveled, offbeat and slightly crude. Whatever is slick, or even familiar, seems to fall by the wayside. At Franklin Parrasch Gallery, large paintings by the skateboarder, poet and visual artist Mark Gonzales were on view (two of which had sold, each for $8,000) with misspelled scrawls of poetry and goofy figures that recalled the ethos of the other outliers. “His work is all about inclusion,” says Parrasch—a statemtent that could be applied to the fair generally.