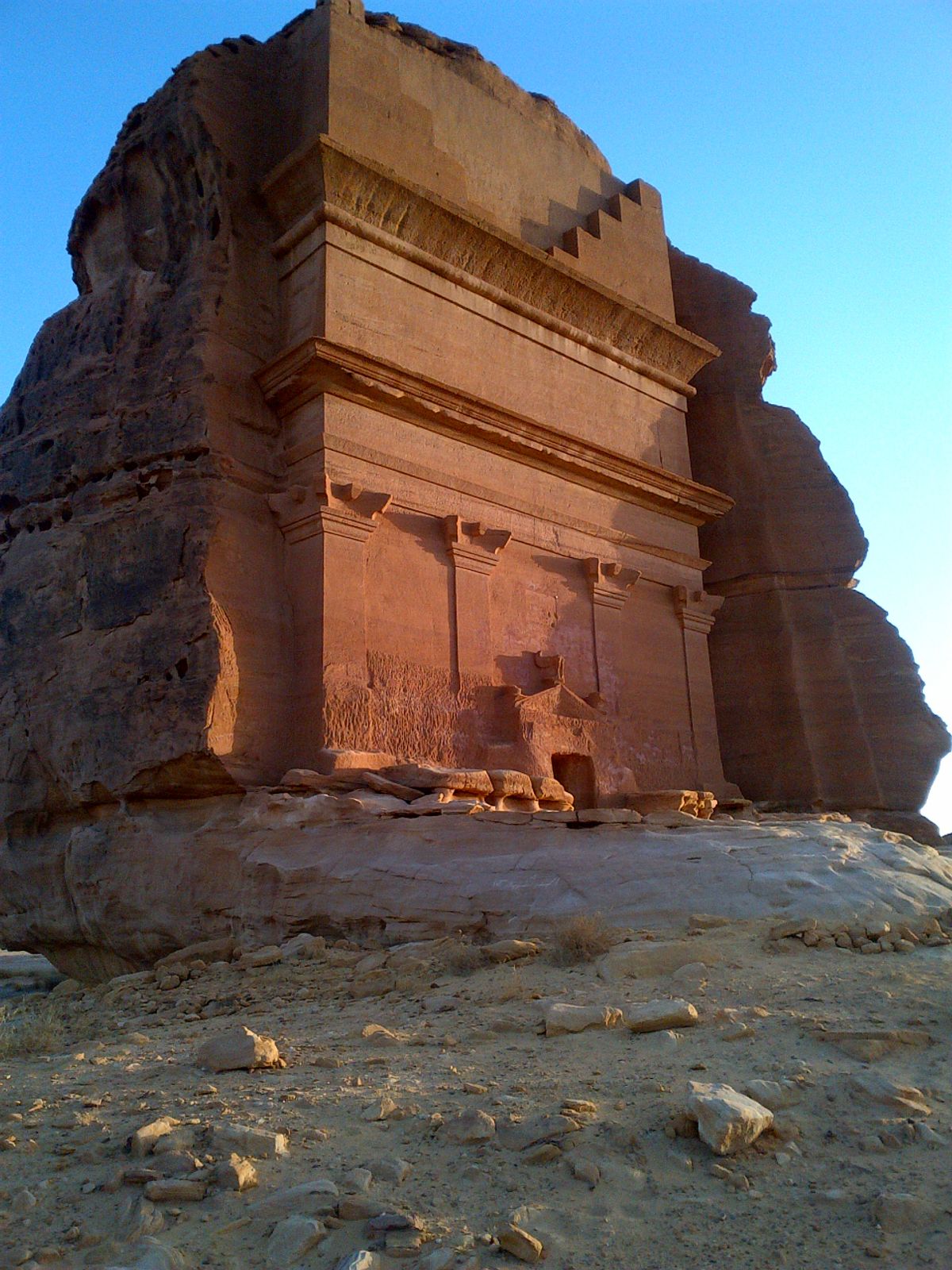

In case you haven’t noticed, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud (known as MBS) is in town. To counter protests by campaigners against his war in Yemen and the continuing abuse of human rights in the Kingdom, sides of buses, newspapers, and even the Guardian’s website carry large advertisements with his handsome face and slogans about what he intends for his country: “He is empowering women”; “He is bringing change to Saudi Arabia”; “He is opening up the country”. On the last, there is a classical tomb carved into a rock face, but no explanation as to where or what it is.

I know. I am one of the very few people to have been allowed to see Mada’in Saleh, the southernmost settlement of the Nabateans, whose city of Petra in Jordan is one of the wonders of the world. Mada’in, known as Hegra in ancient times, is out in the sandy wastes 400km north of Medina. The site, which mostly dates from the first century AD, has hardly been excavated yet, but 111 tombs rise out of the desert, carved into the yellow sandstone.

Saudi Arabia does not have a tourist industry—one of the many things that MBS has said he wants to change—so you have to have special permission to get into the country and even more special permission to travel around it, particularly if you are a woman.

In 2013, I was the guest of Mohammed Hafiz and Hamza Serafi of Athr Gallery in Jiddah, who have plenty of wasta (influence) and can reach no less a figure than the governor of Medina Province, Prince Faisal bin Salman Al Saud.

In 24 hours, everything suddenly became possible, and with two chaperones I found myself being driven fast out of the holy city of Medina. Mile after mile of desert went by. Then, suddenly, there were the tombs with their classical pediments and the eagles of Rome. It was a shock and unexpectedly moving to see our world, preserved in stone so deep into Arabia and the heartland of Islam.

Mada’in Saleh Anna Somers Cocks

Actually, it is a miracle that Mada’in Saleh has been preserved, because the local legend is that the inhabitants of the town were struck dead after refusing the message of monotheism preached by the prophet Saleh (mentioned in the Qur’an) and killing a holy camel. Djinns were said to have moved into the ruins and there were destructive rumblings against the site in recent years when the influence of the Wahhabi clerics was at its height.

Some people still want to keep visitors away—a few years ago, four French travellers were murdered by Al Qaida—but under the protection of Prince Faisal, I was received with full honours and a guide wearing a fine, white head cloth with “Givenchy” woven into its border. I complemented him on it and he said that he had bought it in Regent St while doing a course in tourism studies, so the movement to open up tourism predates MBS.

In fact, Prince Faisal is a keen architectural conservationist and collects the British painter Walter Sickert, as well as contemporary Saudi art. He too has been keen to let more people enjoy the sights under his control, but maybe it will require MBS, with his daring disregard for precedent and rules, to change all the other aspects of the Saudi system and world view for thousands or just hundreds of infidels to be allowed into the Kingdom.