The art historian and broadcaster Bendor Grosvenor calls vetting for Tefaf, Maastricht “the toughest in the world”. This month, 189 of the world’s leading specialists in fine and decorative art—from Old Master paintings to 20th-century design—will gather to work their way through the objects in the fair. They are the final line of defence, after the dealers and the Art Loss Register have done their work, on authenticity, provenance and condition.

“We’re judging ‘beef on the hoof’,” says Edgar Peters Bowron, the head of the 23 experts on the French, Italian, Spanish and British Old Master paintings committee. He is typical of the calibre: formerly the curator of European paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, his CV includes leading roles at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and Harvard Art Museums in Massachusetts. “You have to have the experience of looking at and handling paintings over and over, through the years. You need a kind of sixth sense and the confidence to know what questions to ask,” he says.

We’re judging ‘beef on the hoof’Edgar Peters Bowron

The dealers have just three days—from the Saturday to the Monday before the fair’s Thursday opening—to get their stands ready. The event’s high profile, the value of the works involved, the cost of attending and the tight turnaround means that tensions can run high. To make sure that they do not influence the vetting, dealers leave their stands before the process begins.

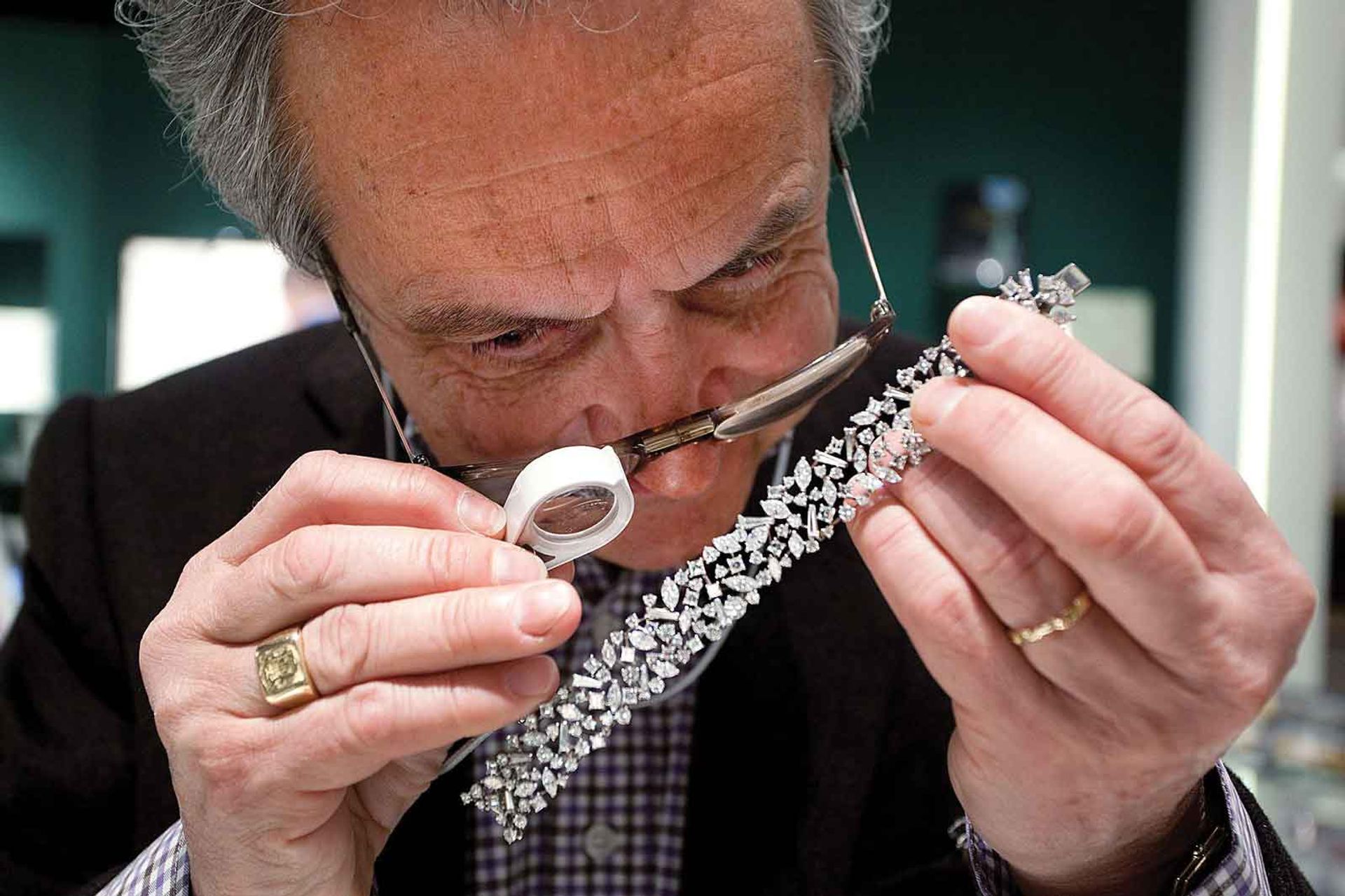

The vetters start first thing on Tuesday. “There were around 200 people, and I didn’t know a single person on my committee,” says Emily Stoehrer, the curator of jewellery at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, remembering her first Tefaf vetting experience. “The director gives a statement, and then it’s a ‘go’, almost like a race. It was pretty overwhelming.”

An expert examining a piece of jewellery

The vetters divide into specialist groups and, armed with Tefaf’s guidelines for each field, work systematically through the fair. “We get the objects list and the keys to the cases. We are checking labelling and authenticity, and we spend a lot of time cross-checking marks,” Stoehrer says. “And we are careful about the integrity of pieces: jewellery can be broken apart and made into something else. Tefaf doesn’t want that kind of thing in the fair.”

Sealed notes are left for dealers asking for further information, requesting that pieces are relabelled or, in extreme cases, rejecting a work of art from the fair. It is “intense”, Stoehrer says. The vetters are spread across two hotels, and have breakfast, lunch and dinner together for the best part of two days. “Being immersed with your colleagues like this is a dream, but it’s also an immense responsibility,” she says.

Most of the specialists come from museums, but in some fields, the experts are in the trade. Simon Andrews is a specialist at Christie’s and the head of the committee of six applied-arts and design vetters. He trained as a furniture restorer, so he has hands-on experience of construction, materials and techniques. He says that understanding the market is also essential.

“One of the reliable indicators of impropriety in the art market is the appearance of similar objects at the same time,” he says. “Our job is a lot easier at Tefaf because the people we are dealing with are at the top of their fields. Smaller fairs can be more challenging because you are exposed to objects from a myriad of sources, and not at the benchmarks for importance that we would see at a fair like this.”

By 3pm on Wednesday, the main vetting is over and the appeals process begins. Andrews says that this is a civilised affair. “Diplomacy is key,” he says. “We keep our thoughts between us [the committee, the fair and the dealer]; there’s no banter, no idle chat. We respect the commitment of the dealers by handling this with discretion.”

But things can, and do, get fraught. “I’ve stepped into restaurants with [Old Master] dealers after vetting, and the temperature has gone down a few degrees,” says Peters Bowron—perhaps unsurprising in a field where a slight change in attribution can mean a price difference of hundreds of thousands of dollars. “But at the end of the day, we are doing our best to act on behalf of visitors and buyers at the fair, so they can really look at pictures with confidence.”

A box in the shape of a hippopotamus’s head (around 1896), at Tefaf with A La Vieille Russie Fabergé workmaster Michael Perchin

TEFAF BY NUMBERS

Around six weeks before the fair, galleries start to submit details of objects to the Art Loss Register (ALR), which checks each one against its databases of lost and stolen art. The ALR flags up objects that need further provenance research—for example, for the period 1933 to 1945—and it is also present throughout the 11-day run of the fair, checking objects that were not pre-submitted and providing certificates for buyers who want more extensive information. Expert vetters, including conservators armed with scientific instruments including X-ray machines, check the authenticity and condition of all items on show at the fair.

Number of galleries in 2018: 287

Number of specialist fields in 2018: 29

Number of objects (source: Tefaf): 12,000 to 30,000 (average 20,000)

Number of objects checked by the ALR in 2017: 12,000

ALR checks before the fair in 2017: 8,000

ALR checks at the fair in 2017: 4,000

Objects flagged by the ALR for further checking in 2017: 600

Number of vetters in 2018: 189

Number of hours spent vetting: more than 3,000

Number of appeals and rejections: undisclosed