Pablo Picasso’s prodigious productivity was such that many single years throughout his career could be the subject of a major show. But the year that is the focus of Tate Modern’s latest blockbuster, 1932, was a crucial 12 months. Professionally, Picasso had his first retrospective in Zurich and published the first volume of his catalogue raisonné. He also produced some of his greatest paintings. Not for the first time, those works emerged from a turbulent private world.

There were essentially two Picassos in the early 1930s: the wealthy public figure, living comfortably with his wife Olga and son Paulo in his apartment on rue La Boétie, and the artist furiously working in his studio in the apartment above, often reflecting his sexual adventures with Marie-Thérèse Walter, his mistress of five years. The great photographer Brassaï, after a visit in September of that year, described the setting for this duality: the family home, he said, was “one of the centres of society life” and the studio was a pigsty. But masterpieces poured from that mess.

Two paintings depicting Walter, one from the beginning of the year, the other from the end, reflect Picasso’s artistic trajectory. The Dream is the most celebrated of three paintings he made across three days of Walter sleeping. They capture Picasso at his most tender, yet still clearly focused on sex: in The Dream, Walter’s hands form a vulvar shape, while the upper part of her head is depicted as a phallus. The painting matches Picasso’s great rival Matisse in its decorative colour and compositional harmony.

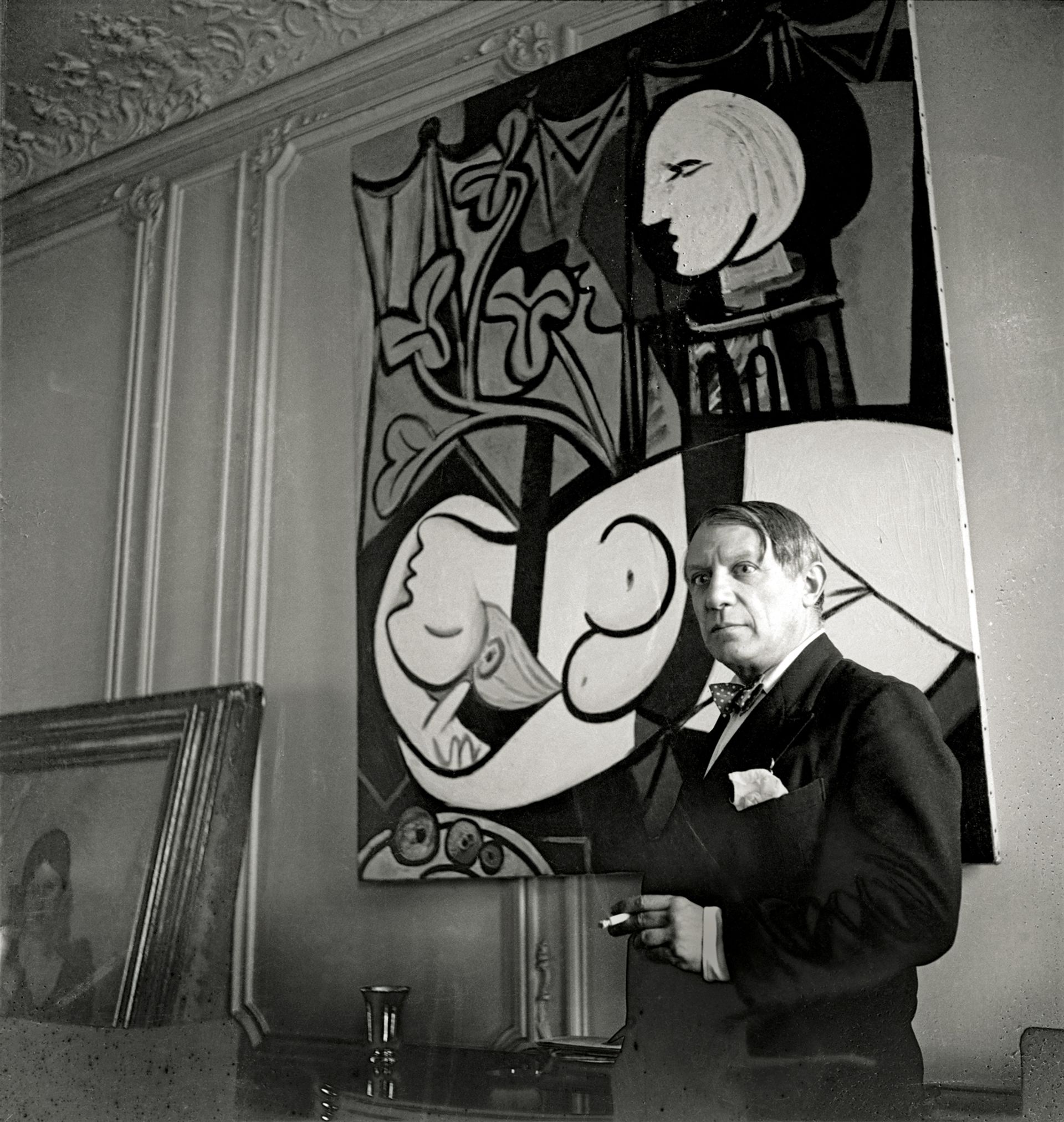

A Cecil Beaton photograph of Pablo Picasso at rue La Boétie, Paris, in 1933 Cecil Beaton Studio Archive Sotheby’s

The mood in The Rescue, painted in November, is entirely different. Here, three figures, all resembling Walter, play out a scene of tragedy as a drowned figure is pulled from water. The sensuous curves of The Dream are gone and instead the figures are more fragmented, the colours muddied, and the forms contained in thick black lines. As well as reflecting Picasso’s lifelong engagement with images of nymphs and bathers, with the mythological Eros and Thanatos, they capture his particular worries in November 1932. Walter had swum in a rat-infested stretch of the Marne and contracted Weil’s disease. She lost much of her hair (the drowned figure in The Rescue might allude to this) and almost died.

As always with Picasso, life and art were inseparably intertwined.

The exhibition is sponsored by EY and was organised in collaboration with the Musée National Picasso, Paris, where it was first shown in October 2017.

• Picasso 1932—Love, Fame, Tragedy, Tate Modern, London, 8 March-9 September