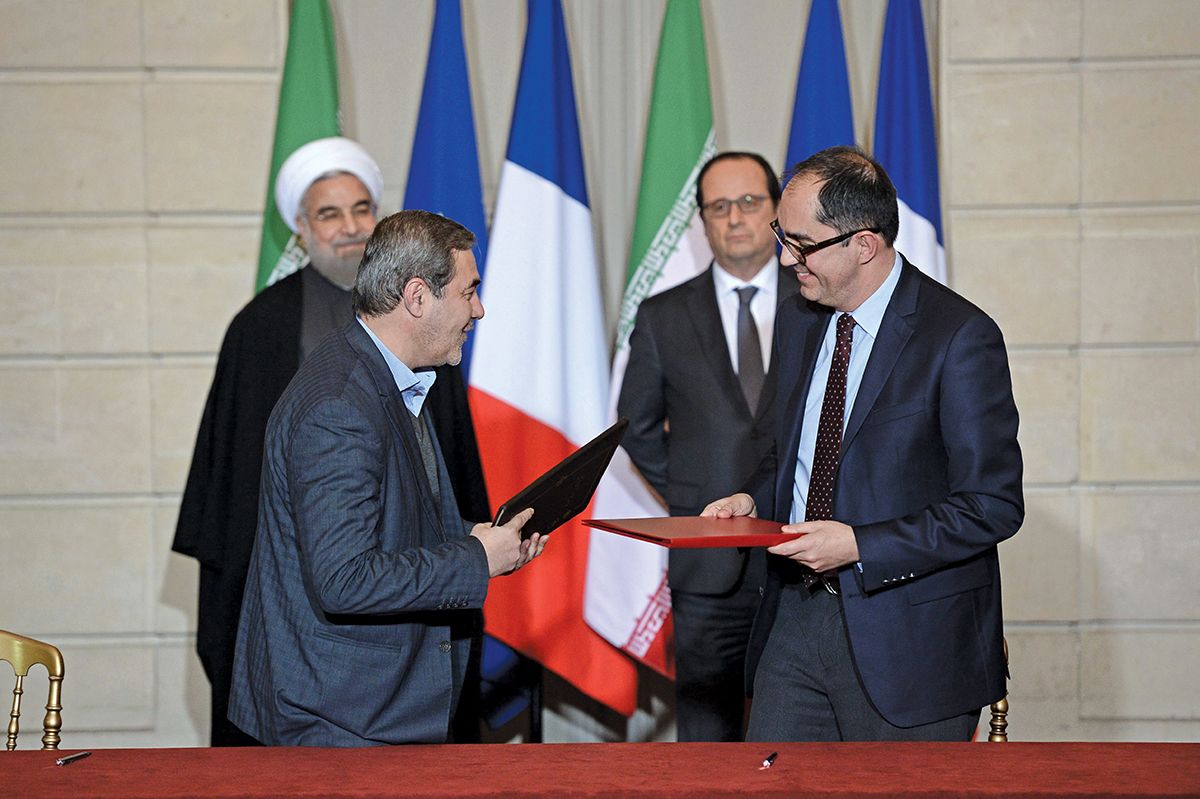

Despite renewed tensions in the Middle East, the Louvre and the Iranian government are pushing ahead with a series of exhibitions and archaeological projects planned under a landmark four-year agreement signed in January 2016. The French museum is the first major cultural institution to secure ties with the Islamic regime since the lifting of trade sanctions by Europe and the US in 2016.

French and Iranian dignitaries attended the inauguration today of a show of works from the Louvre’s collection at the National Museum of Iran in Tehran (The Louvre in Tehran, 5 March-3 June). In exchange, an exhibition on the Persian Qajar dynasty (1786-1925) will open later this month at the Louvre-Lens in northern France (The Rose Empire: Masterpieces of Persian Art from the 19th century, 28 March-23 July). Meanwhile, the Louvre’s Islamic art department is sending an archaeological mission to visit sites for a new dig on the ancient Silk Road in eastern Iran.

“It would certainly be a quieter life as curator of Burgundian Medieval sculpture,” says the head of the Louvre’s Islamic department, Yannick Lintz. A specialist in Persian and Central Asian cultures, Lintz visited Tehran in June 2015 to research loans for the Qajar show. The Louvre-Lens will be the first European institution to survey a period that represents “the entry of Persia into the modern world”, Lintz says.

Four decades after the Iranian revolution, the initial meeting “was quite a challenge because I wasn’t sure what kind of response I would get for an exhibition on this monarchic past”, she says. But her hosts at Iran’s Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organisation welcomed the idea, expressing a wish for a parallel exhibition in Tehran. They accepted the proposal to show a sample of the Louvre’s collections to celebrate the 80th anniversary of the National Museum, which was designed by a French architect, André Godard.

Both parties were acutely aware of the precedent of 2011, when Iran cut all cultural ties with France, accusing the Louvre of reneging on a promise to exhibit Persian artefacts in Tehran. The French museum is now presenting 56 works at the National Museum, including monumental Egyptian, Assyrian and Roman statues, a Corot landscape and a portrait of an Ottoman Sultan. Two antiquities from Iran, chosen by curators from both countries, are also part of the show.

François-Henri Mulard’s Napoleon Receives the Persian Ambassador at Finkenstein Castle (1810), one of the works heading to the Louvre-Lens exhibition © Château de Versailles/RMN-GP/Franck Raux

The show must go on

Nevertheless, tensions late last year between Iran and the US, along with Saudi Arabia, rattled the Louvre. Would-be exhibition sponsors shied away, clearly remembering the record $8.9bn fine imposed by the US on BNP-Paribas in 2014 for violating sanctions against Iran, Cuba and Sudan. Peugeot, which has a third of the car market in Iran, declined to sponsor the show. But the Iranian branch of its rival, Renault, has come on board, following the French oil and gas giant Total—the first major Western energy company to sign a contract with Iran since sanctions were lifted.

As sponsorship and logistics became more complicated, the number of loans from the Louvre to the National Museum was reduced. There is now only one cargo flight a week between Paris and Tehran—managed by Turkish Airlines, which raised its tariffs. Despite the difficulties, Lintz says, the Iranians were willing to continue the collaboration. Around 30 Iranian works will be among 450 paintings, photographs, jewels and films in the Lens show. The Royal Palace of Tehran has agreed to lend regalia that have not been seen abroad since the Islamic Revolution. In December, the Louvre received authorisation for an archaeological dig in Iran, in the Khorasan region.

For the past five years, the French museum’s director, Jean-Luc Martinez, has focused mostly on improving visitor conditions in Paris. In the wake of the success of Louvre Abu Dhabi, however, he is warming to the idea of other projects abroad. Clearly, the Louvre remains a key player in France’s cultural diplomacy. The French foreign affairs minister Jean-Yves Le Drian, who postponed a trip to Iran in January due to widespread anti-government protests, held talks with senior officials in Tehran today (5 March) in a bid to salvage the 2015 nuclear deal.

Lintz notes that the Louvre opened an exhibition on medieval Morocco in 2014, a moment of difficult relations between the two countries. The Moroccans later told her they were grateful to have maintained dialogue at a time when all other channels were frozen. “If we can help achieve better understanding, so be it,” she says.

A 19th-century Iranian sculpture of a cat Musée du Louvre/RMN-GP/Hervé Lewandowski