Certain exhibitions are landmark events. Outliers and American Vanguard Art at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, is one of them. The show of around 250 works by more than 80 schooled and unschooled artists from between 1924 and 2013 stakes a clear and demonstrable claim: that American Modernism and outlier art—a more flexible and inclusive term than the older “outsider,” “folk” or “naive” designations—are far closer historically than we have been led to believe.

Instead of inventing a new narrative, the show largely draws out old points of convergence between avant-garde artists and outliers that have long been obscured by orthodox divisions. It is an integrationist exhibition, beginning in the historical center, with established artists such as the American Precisionist painter Charles Sheeler, who praised Shaker furniture for its seeming modernity, and expanding outwards to reabsorb the extremities that have since been pushed out. The curator Lynne Cooke’s goal is not radical reinvention, but instead to demonstrate the historical closeness of traditions that have long relied on one another, and to show the solvency of the old story, which needs only correction and elaboration, not wholesale disassembly.

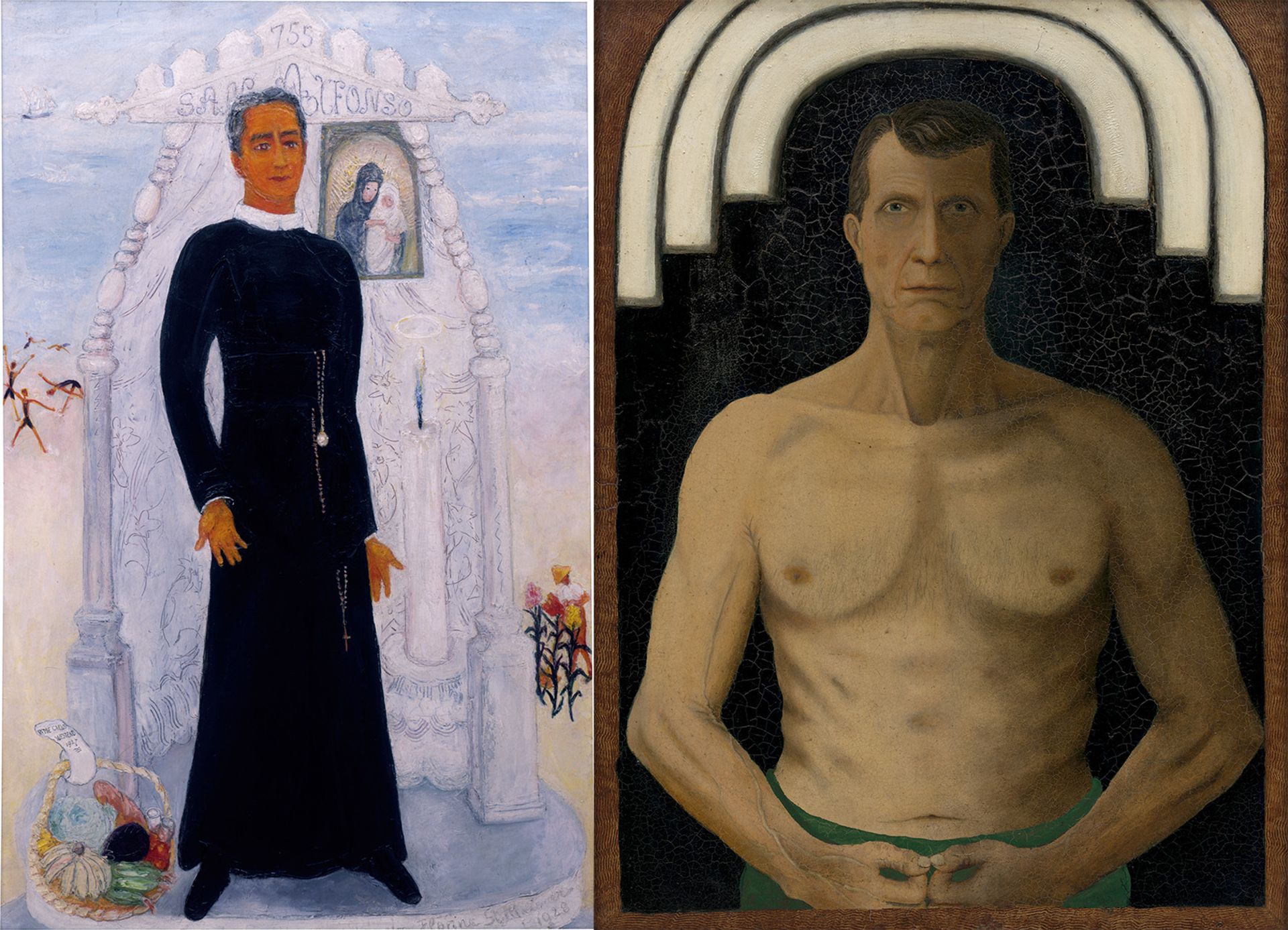

In one gallery, there is a picture of a priest in a simple black garb against a hazy, mystical and flattened background. It is painted in a sincere and simple folk style by Florine Stettheimer (1871-1944), the gifted artist and wealthy Manhattan saloniste. Nearby, there is a similarly “naive” portrait by the self-taught painter and one-time Pittsburgh manual laborer John Kane (1860-1934), where he depicts himself against a comparably shallow backdrop (this time black instead of Stettheimer’s white) with his head surrounded by a trio of haloes. These paintings look better together than they do separately, in part because they indicate the complexity and reversibility of history. Whereas Kane became celebrated in his lifetime and showed his work at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Whitney, Stettheimer held much of her painting from public view while still hosting soirees that drew Modernists such as Alfred Stieglitz and Marcel Duchamp.

Florine Stettheimer's Father Hoff (1928) and John Kane's Self-Portrait (1929) University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Gift of the Estate of Ettie Stettheimer; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund, 1939 © The Museum of Modern Art/ Licensed by SCALA/ Art Resource, NY Order

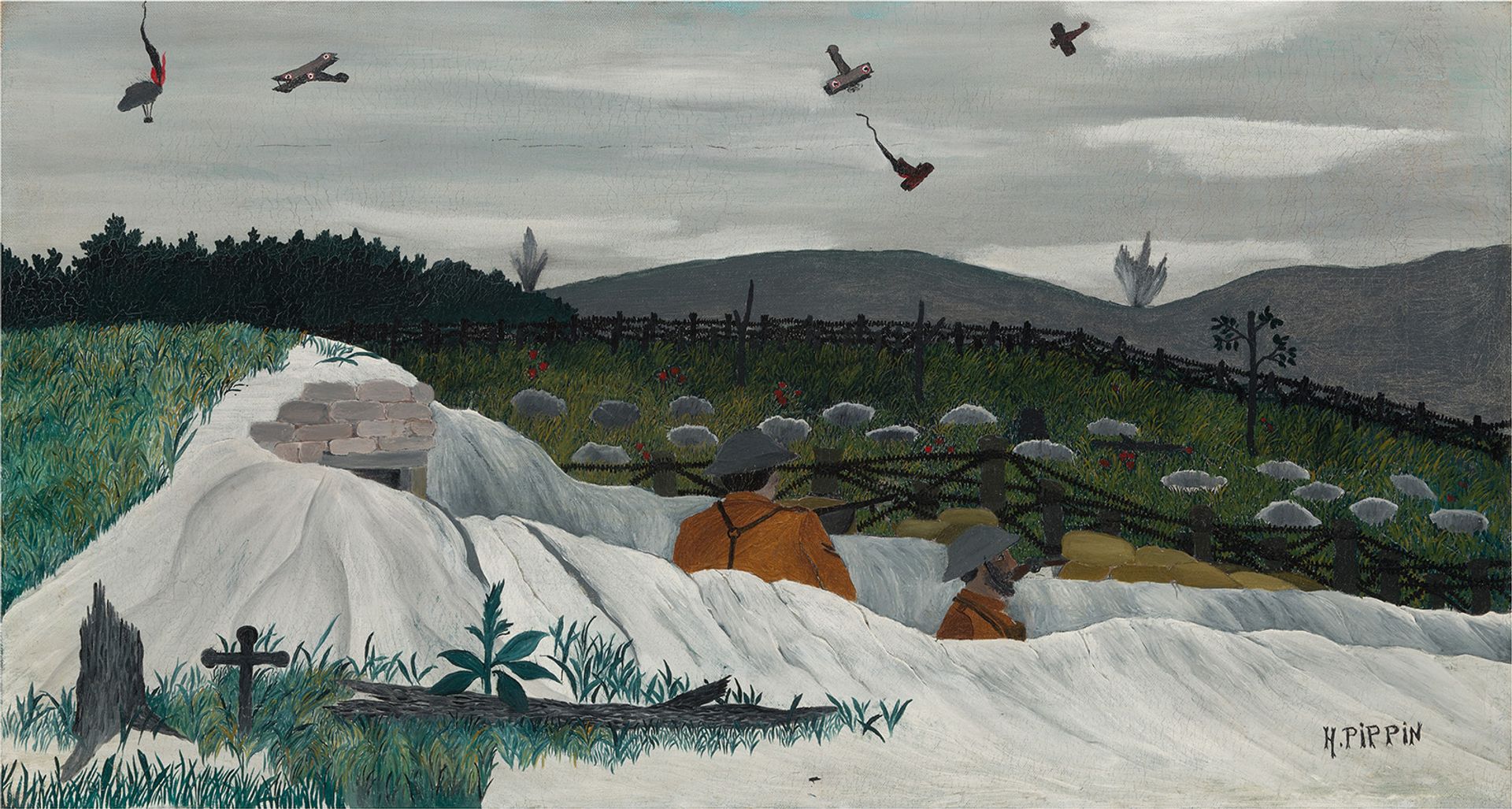

Cooke’s organising principle is to focus on three periods in which the overlaps between the inside and outside were most generative: 1924 to 1943, 1968 to 1992, and 1998 to 2013. (These eras are discussed in the show’s illuminating catalogue, which includes articles by the art historians Darby English, Richard Meyer and Thomas Lax, among others.) Kane and Stettheimer come from the first phase, as does Horace Pippin, one of the most powerful painters of his time. In 1928, after an honorable military discharge, he began to teach himself how to paint in oil. Like Kane, he garnered praise and his art was shown in museums, but his pictures are more anxious than Kane’s, with a constant sense of implied violence. Pippin’s remarkable painting John Brown Going To His Hanging (1942) shows the radical American abolitionist, who butchered supporters of slavery in Kansas in 1856, seated in a coach, tied up but calm, and surrounded by a subdued mob eager to see him die.

Pippin is one of many black artists in the show, and as the exhibition shifts into its second historical phase, from 1968 to 1992, a specific strand of African American art history comes into focus. The history was elaborated most richly in 1982, when the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC, hosted the exhibition Black Folk Art in America, 1930-80. The show was organised by John Beardsley and Jane Livingston around a simple but radical claim: that black folk art was part of a living contemporary art tradition, no matter how removed it was from institutional discussion. The argument still stands. Some of the most contemporary works of art in the National Gallery's exhibition were made outside the acknowledged centres of the art world. Steve Ashby—who was born in 1904, the son of a former slave, and who never left his small Virginia town—made a simple figurine sculpture of a white hunter looking through his riflescope at the dead body of a black man. What could be more relevant today?

Horace Pippin, Dog Fight over the Trenches (1935-1939) Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1966

These first two phases of the exhibition are revelatory. But later, when works of art by Cindy Sherman and Matt Mullican start to appear alongside examples by non-academics like the photographer Eugene Von Bruenchenhein and the illustrator and writer Henry Darger, the pace and power slacken. When it comes to very recent art, there is less for Cooke to uncover, and she must invent new connections. Her argument—“a new paradigm has emerged, one that positions trained and untrained artists on a level playing field without hierarchical distinctions”—is more a wish than a reality, and the solution—to assemble “works on the basis of shared materials, processes, or themes, without regard for the professional status of their makers”—does not satisfy.

Yet she makes an implied point: that in some circles, at least, there has been a real collapse of prior distinctions. The art market, for example, has made a headlong rush to assimilate outlier art. The Outsider Art Fair is this year adding the city of Basel to its editions in New York and Paris and last December, Christie’s had a New York sale titled Outsider Art: The Hot List. Market acceptance is a true measure of success. But those pesky class distinctions—who can afford to buy what—around which outlier art has so often been organized, have never gone away.

Regardless, Outliers and American Vanguard is full of welcome surprises, even if the work is not uniformly stunning; some of it, like the Yale-taught sculptor Jessica Stockholder’s, is outright dippy. Yet part of the point is that everyday designations—good and bad, ugly and beautiful—should be put constantly under stress. We do not see only with our eyes; the world we live in also conditions our tastes. Backgrounds and educations, exposure to difference or lack thereof, our willingness to imagine other’s ideas—these also shape what we think is inside and outside. What’s the story? Who fits into it, and who doesn’t? Distinctions are inevitable. But they must be made with real self-awareness. The great success of this exhibition is to stress that point through the tightness, as Darby English writes in the catalogue, between “modernism and its nearest outer layer”.

• Outlier and American Vanguard Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, until 13 May 2018; travels to the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, 24 June-30 September and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 18 November-18 March 2019