The opening sequences of the first episode of Civilisations, the BBC’s much-anticipated new series, are among the most stirring pieces of television made in some time. They also unavoidably suggest the handing over of a baton from Kenneth Clark’s 1969 series Civilisation, whose name the new series self-consciously adopts and, by adding that final S, subtly yet tellingly adapts. Clark ended his series optimistic about a well-fed and well-read youth, but amid sequences of St Paul’s Cathedral lashed by fire in the Blitz and images of atom bomb explosions and the desolation they wrought, he concluded that “the future of civilisation doesn’t look very bright”.

The explosions that appear in the first episode of Civilisations, presented by Simon Schama, are not as apocalyptic as those nuclear mushroom clouds, but powerfully evoke the threat that has superseded nuclear holocaust in this century: global terrorism. Against footage of Isis destroying ancient art in Mosul, and bird’s-eye views of Palmyra, Schama tells the story of Khaled al-Asaad, the scholar who refused to lead these new barbarians to the city’s treasures, hidden for safekeeping. “They beheaded him in a Roman theatre, suspended his mutilated body from a traffic light, placed his head between his feet and attached a placard identifying him as ‘director of idolatry’,” Schama tells us. He then adds: “Or we might say: protector of what needs to be saved, cherished—passed on as the work of civilisation.”

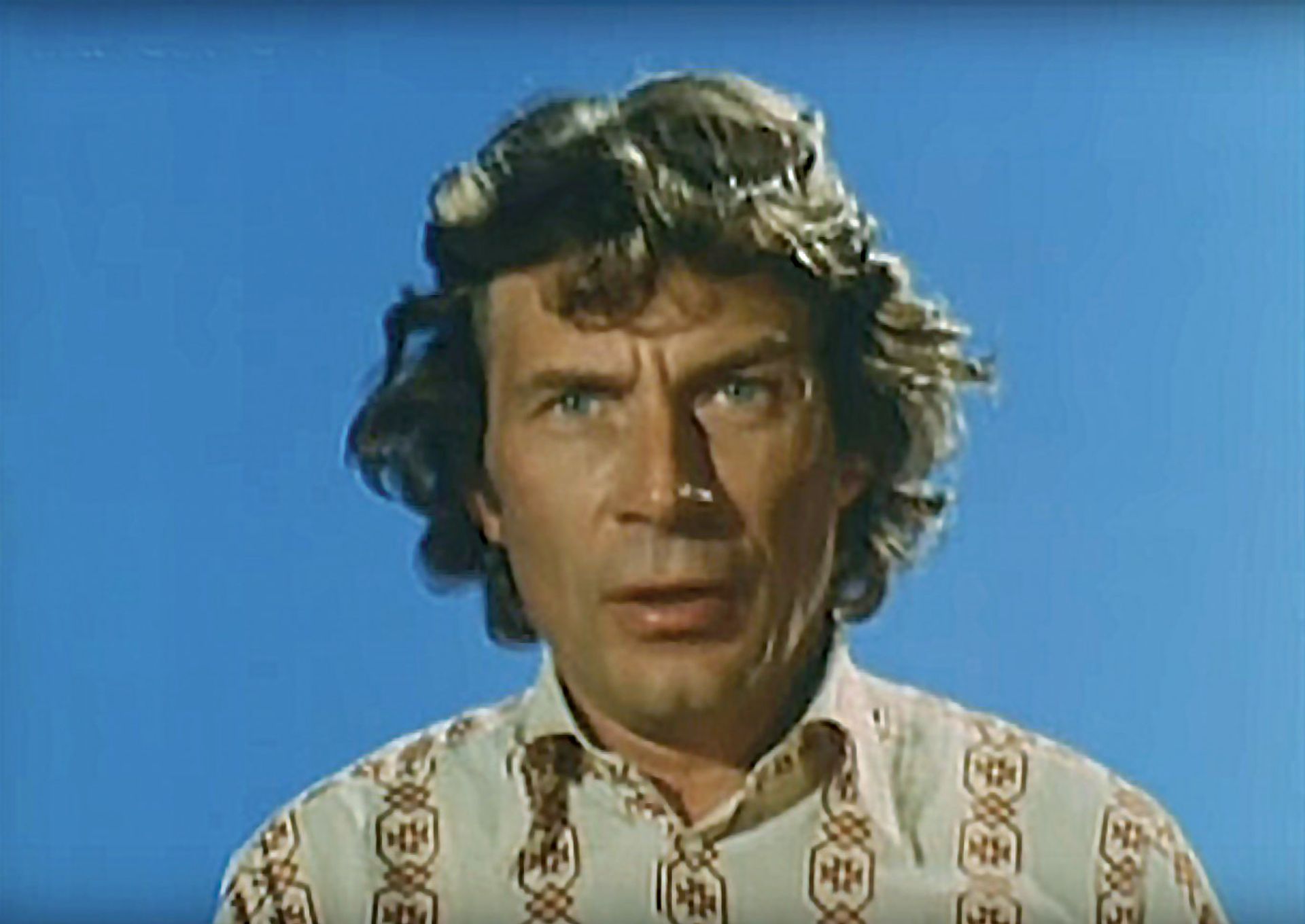

Kenneth Clark in Civilisation Courtesy of the BBC Archives

At the start of his series, Clark asked: “What is civilisation? I don’t know. I can’t define it in abstract terms, yet. But I think I can recognise it when I see it.” Turning to Notre Dame, he added: “And I’m looking at it now.” Schama, shaken by Isis brutality, is certain: “We can spend a lot of time debating what civilisation is or isn’t,” he says, “but when its opposite shows up, in all its brutality and cruelty and intolerance and lust for destruction, we know what civilisation is, we know it from the shock of its imminent loss, as a mutilation on the body of humanity.”

It is an emblematic opening, says Mark Bell, the BBC’s arts commissioning editor. “What we wanted to show was that these cultural artefacts are, some of them, very long lived, but also quite fragile, and also quite contested—what they mean to different people is slippery and that’s interesting.”

The idea of contested meanings is a marked shift from Clark’s series. Its subtitle, A Personal View, is often forgotten by both its critics and its supporters, as is the clear brief from David Attenborough, the then controller of BBC2, for Clark and the director Michael Gill to focus on European civilisation. This was a spectacular personal essay, a singular view of European culture, whose protagonists were “a small sample of the great men that Western Europe has produced during the past thousand years”, Clark said. He unashamedly believed in “the god-given genius of certain individuals” and they dominated his series.

Bell says that, while the makers of Civilisations “acknowledge the debt and inspiration” of Clark and Gill’s series, they had to forge something new. “We started off making this, thinking: ‘What would it be like to make a programme like [Civilisation] now?’ And quite early on, we came to the conclusion that we’d need to go broader, that we live in a world that is much more diverse and our understanding of and appreciation of different cultures has changed in 50 years.”

This shift is palpable in Schama’s first programme, which takes us from Europe through Africa to the early civilisations of China, Mexico and the Middle East. As well as geographic breadth, it has an epic temporal arc—beginning, unlike Clark, with the very first human creations in the caves of Spain and Africa. Despite these differences, the series is not “an answer to Civilisation”, Bell says. “The intention was to make a programme inspired by Civilisation, but looking at the themes through the context of our present. I don’t see it as being a riposte in any way, it’s an addition to it, and it’s very different.” Indeed, the BBC will make Clark’s series available to viewers on its online iPlayer, so viewers can view them side by side.

A divisive lens

Perhaps the most palpable difference is in its presenters. Civilisations, too, is about personal views, but those of three people: Schama, who presents five programmes, and Mary Beard and David Olusoga, who each present two. As Bell says, Schama’s approach most closely resembles Clark’s. “If there’s a Clarkian around now, it’s probably Simon. I think he would acknowledge that there’s a debt there.” But there is a huge difference in the passion with which Schama delivers his thoughts, compared with Clark’s stuffy reserve. A sequence in which Schama rhapsodises about a recent discovery of Mycenaean art is enthralling in a way Clark never manages to be.

But Mary Beard’s first programme (episode two) comes closer to a direct critique of Clark. Called How Do We Look?, it focuses, unsurprisingly for Beard, on the art of the ancient world, beginning with Olmec heads in Mexico, through Pharaonic figures in Egypt and terracotta warriors in China, to ancient Greco Roman statues. But there’s a powerful moment at the end of the episode: Clark himself appears in an excerpt from Civilisation.

Beard is discussing the famous Greco-Roman statue the Apollo Belvedere and the influence of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the 18th-century writer often called the father of art history. He elevated the statue “above a mere artwork”, Beard tells us, and sought to argue that “you could track the history, the rise and fall of civilisation through the rise and fall of the representation of the human body”. Beard then adds: “Winckelmann’s views would seduce even our most esteemed art historians.” Cue Clark’s appearance: “The Apollo surely embodies a higher state of civilisation,” he says. Beard then argues that Winckelmann’s inheritance “has been a distorting and sometimes divisive lens, deeply affecting the way people in the West have encountered and judged the art of other, very different civilisations. I think Winckelmann has caught us in a narrow way of seeing that’s difficult to perceive, much harder to escape.”

This is more radical than many might have dared to expect from Civilisations. Beard’s use of the term “way of seeing” can’t be coincidental: it evokes the title of John Berger’s BBC series, which was a direct riposte to Clark. And Beard admitted in an article in the Guardian newspaper in 2016 that, while Civilisation had made an impression on her when she saw it in 1969, she grew to be a “devotee” of Berger’s book and series. She became “decidedly uncomfortable with Clark’s patrician self-confidence and the ‘great man’ approach to art history—one damn genius after the next—that ran through the series”, she wrote. Clark’s characterisation of the barbarian hordes was, she argued, “as crude an oversimplification of barbarism as his dreamy notion of ideal perfection was an oversimplification of classicism”. But Civilisation had still opened her eyes, she conceded: “not only visually stunning, it had shown us that there was something in art and architecture that was worth talking, and arguing, about”. How Do We Look? simultaneously reflects what Beard admired and disliked about Civilisation: it is as dramatic and visually gorgeous as Clark’s series was for viewers encountering the new medium of colour television in 1969; it very much proposes an argument; yet it undoubtedly reflects shifts in art historical thinking over the intervening years.

John Berger presenting Ways of Seeing BBC

Clark’s long shadow

Berger’s Ways of Seeing represented just one approach taken by those trying to find different ways to stage those art historical arguments on television. But as John Wyver, the producer of many visual arts documentaries over the last four decades with his production company Illuminations, says: “Because of its budget and its scale, [Civilisation] was profoundly significant and defining for almost every arts documentary series ever since. Whether you worked with that dominant form, or you tried to find an alternative to it, absolutely you were working in its shadow.”

Together with the curator Sandy Nairne, who went on to become the director of the National Portrait Gallery, and his colleague Geoff Dunlop, Wyver made the now unjustly neglected series State of the Art for Channel 4 in 1986. “We very self-consciously saw ourselves working in a line that was Civilisation, Ways of Seeing and [Robert Hughes’s series on Modern art] The Shock of the New,” he says. But they were also trying to do something different. “There are differences between them, but there are also raw similarities,” Wyver says. “Obviously, all three of them have got white blokes standing in front of works of art. We wanted to find an alternative to that, so we didn’t have a presenter [for State of the Art]. We fragmented the narrative voice among four essentially anonymous voices, and we built the narrative and the voiceover script almost entirely out of quotation, each of which we acknowledged and recognised in the soundtrack.”

Looking at State of the Art today, it is remarkable how radical this idea of a dialogue between thinkers remains. “I can’t say this definitively, but I am not sure that Clark acknowledges any previous art historian in Civilisation,” Wyver says. “And this is the case pretty much whether you’re Robert Hughes, or [the UK critic and broadcaster] Andrew Graham-Dixon, or Simon Schama—it is as if the ideas that are expressed in arts documentaries have come from the mind of the presenter, without a recognition that she or he is working in a tradition, drawing on previous ideas and responding to them or engaging with them in different ways. It is one of the fundamental differences between art history on television and art history in even journalism, let alone in academic work: there’s no recognition of the context in which the ideas are being put forward.”

This evokes another striking moment in Beard’s first Civilisations episode, where she sits in a library reading Winckelmann, laying bare the process of art historical argument. But still, in visual terms, most of the programme is palpably in the idiom of Clark rather than Berger or State of the Art; and it is a tradition that goes back centuries. “It’s really important to recognise that Civilisation crystallised, in a new medium, a range of forms and ideas and concerns that had been developed in other contexts,” Wyver says. He cites formats with “a long and potent history that have been proven to work for audiences”: the 19th-century art history slide lecture, invented in Germany; the Grand Tour with the expert guide taking aristocrats around Europe; and the travelogue shows using film and slides of Elias Burton Holmes. “Clark was able to bring together his worldview, and his understanding of the arts, with technology, a really lavish budget and a public service broadcasting context that permitted him to develop those ideas in a really potent and significant way. It unquestionably touched many people and shaped many people’s views of Western art. It arrived at the right moment, in a way, and it has been pretty dominant ever since.”

Wyver is only too aware of what can happen if one steps too far from the established form. “As I remember it, [the critic] Peter Fuller opened a column saying: ‘I started to watch State of the Art and I wept’,” he says. So that series must remain in another tradition of documentaries, exemplified by the work of Mike Dibb, Berger’s collaborator on Ways of Seeing. It is a history that, as Wyver says, has “never been the valorised or central tradition in any way”, despite the films being shown on mainstream channels in their day. Wyver is clear that such radical films are unlikely to be made by the BBC or other mainstream channels today.

Much is riding on Civilisations for the BBC, amid debate about the organisation’s value in British cultural life. One senses it had to be classic, evoking Clark’s heyday, yet reflective of the modern world. “We made it in the way that we felt we should make it, in the way that Clark and Gill made the original,” Bell says. “It wasn’t a showcase of BBC values then, but all BBC programmes are to some extent. Civilisation was of its time but stood the test of time, and I hope that people will watch Civilisations and find it of interest, find it illuminating.”

On the evidence of the first two programmes, that aim should be fulfilled. But there is no doubt that the story now goes beyond just a few men of god-given genius. “The history of art,” Beard tells us in episode two, “isn’t just a history of artists, of the men and women who painted and sculpted, it’s also the history of the men and women who looked, who interpreted what they saw, and the changing ways in which they did so. If we really want to understand images of the body, I think we’ve really got to put those viewers back into the picture of art.” Something, to use Beard’s phrase, worth talking, and arguing, about.

The Presenters

Simon Schama

Writer, presenter and project consultant

Simon Schama Nutopia

Schama presents five of the nine Civilisations programmes. A professor in art history and history at Columbia University, New York, and a contributing editor of the Financial Times, he has made several award-winning TV series, including Simon Schama’s Power of Art and The Face of Britain.

Mary Beard

Writer and presenter

Mary Beard Nutopia

Indisputably Britain’s best-known classicist, Beard is a professor at the University of Cambridge and classics editor of the Times Literary Supplement. Her radio and television work has included the stirring Pompeii: Life and Death In A Roman Town, Meet The Romans, Caligula with Mary Beard and, this year, Julius Caesar Revealed.

David Olusoga

Writer and presenter

David Olusoga Nutopia

The British-Nigerian historian and broadcaster has become a fixture on the BBC in recent years, with programmes including The World’s War: Forgotten Soldiers of Empire, the recent, excellent series A House Through Time and the Bafta-winning Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners.

• Civilisations is on BBC Two from 1 March, when all the episodes will be available at once on the BBC iPlayer. In the US, the series airs on PBS from 17 April