The Middle East has little in the way of official authentication boards, and as the number of fake works in this young market grows, artists’ families are setting up their own. This step has been applauded by those who see family-run foundations as the best means of policing a fast-rising market. Hala Khayat, Christie’s head of sales in Dubai, says the auction house works closely with deceased artists’ families and discusses with clients “the importance of paying the extra money for the certificate of authenticity, which is a new phenomenon in the Middle East”.

Around 20 active family estates and foundations are now known across Iraq, Iran, Jordan, Egypt and Lebanon. However, charging up to €2,000 for authentication certificates also raises questions about the motives and expertise of artists’ relatives, particularly where conflict has damaged other archives, museums and libraries.

Moreover, protecting a legacy can tip over into attempting to control an artist’s reputation by denying the authenticity of works that do not fit with the family and/or artist’s vision of their position within art history. When museums and collectors of major Modernist artists are repeatedly denied authentication or copyright use for the works they own, as in the case of Iranian-born Charles Hossein Zenderoudi, bitter struggles have ensued.

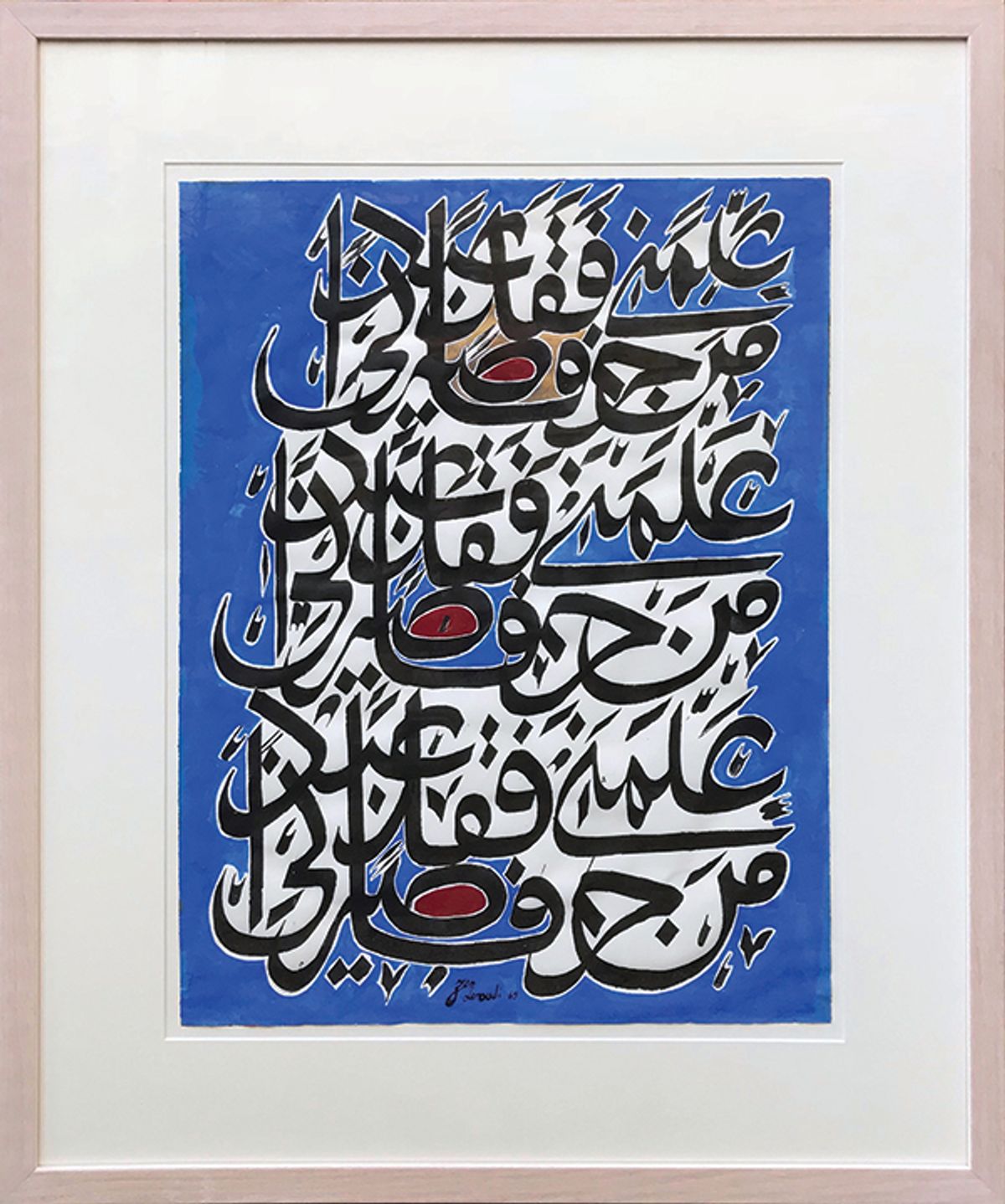

Charles Hossein Zenderoudi

Zenderoudi, born in Iran in 1937 but a long-time resident of France—where artists hold the right to authenticate their own work in perpetuity—is a contentious example. The artist, his wife, Marie, and their children fiercely protect the attribution of his work and guard his legacy, and in recent years have turned down numerous applications for authentication and image, particularly for his calligraphic works. In the past decade the financial stakes have risen sharply—Zenderoudi’s auction record stands at $1.6m, for the abstract oil on canvas Tchaar-Bagh (1981), sold at Christie’s Dubai in 2008. But if a collector’s work is rejected as authentic by Zenderoudi and his family, it is virtually worthless.

Kamran Diba, an Iranian architect and artist who designed the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, reacted angrily when Zenderoudi refused to authenticate a signed calligraphic work which Diba says was commissioned by his father directly from Zenderoudi more than 40 years ago.

“I was his biggest collector, I was his mentor, I told him which paintings were good and which were bad, I’m an artist myself,” Diba says. “I was pushing his work to all my friends, they have a few Zenderoudis from those days.”

Foundations, Diba suspects, can be an easy way for families to make money: “They take money, close to $2,000, and then they say yes or no but don’t give your money back.” Diba believes the trouble surrounding his Zenderoudi came after he questioned whether another of the artist’s paintings—which he said he had encouraged the artist to paint on canvas rather than paper—had been back-dated to an earlier period.

Zenderoudi was a wonderful artist in the 1960s, 1970s, and then... In the past decade, since the market picked up, his wife and son are obsessed by saying he is not Iranian, not a calligraphistRose Issa

The Geneva-based collector Jean-Pierre Jacquemard, who was introduced to the painter by Diba, recounts a similar story about a work that he says was one of two bought directly from the artist in 1970. After one work was sold at Sotheby’s around a decade ago for £60,000, Marie Zenderoudi told the auction house the second was a fake. In 2015, Jacquemard’s son paid €1,900 to get a painting certified by the family. It was not confirmed and the reply included a threat to sue, signed by the 80-year-old Zenderoudi with just his initials.

The London-based curator Rose Issa, a long-time champion of Middle Eastern art, was refused the right to use images of Zenderoudi’s work in the book, Signs of Our Times, from Calligraphy to Calligraffiti, which she co-authored in 2016. “He refused to be associated with Middle Eastern artists or calligraphy, although, in the book, out of 50 artists only three were calligraphers,” Issa says. “He was a wonderful artist in the 1960s, 1970s, and then... In the past decade, since the market picked up, his wife and son are obsessed by saying he is not Iranian, not a calligraphist, which is their right, but [they] never give permission if the subject is Iran and not international”, she says.

The art historian Sussan Babaie, currently reader in the arts of Iran and Islam at the Courtauld Insitute of Art, says Zenderoudi and his wife denied her permission to use an illustration in an article in 2011 for the Getty Research journal unless she described him, using their text, as the sole founder of the Saqqakhaneh Modernist movement in Iran, which also famously included Parviz Tanavoli. Zenderoudi's denials, she says, have “detracted from analytical consideration of his role in the two decades ordinarily associated with the emergence of a Modern movement contemporary with those in Europe and America. All we know about Zenderoudi's remarkably beautiful paintings is a couple of clichés. That is a real shame.”

Mohammed Afkhami, a leading collector of Iranian art, was also denied the right to use an image of a Zenderoudi work that he owns for the lavish catalogue of his collection, published last year by Phaidon. “Despite numerous efforts… we were regrettably denied, with no explanation provided,” Afkhami says. Zenderoudi’s entry is the only one of the 100 artists in the catalogue without an image—just seven printed captions and a blank page.

When contacted about these cases, Zenderoudi replied, in French: “In response to your emails of 11, 12, and 14 January 2018, in which you question the authentication of my works, I remind you that, as an artist, the authentication of the works of which I am the author belongs to me.”

Paul Guiragossian

Not all foundations are quite so controversial. One of the oldest in the region is run by the family of the Armenian-Lebanese painter Paul Guiragossian (1926-1993). His daughter, Manuella, is the youngest of five siblings who work with their mother to maintain the estate; they also own several hundred works. The foundation, established in 2011, charges up to $2,000 to evaluate paintings; it authenticates around 30 a year and has so far identified around 100 fakes. Manuella says fakes began to appear when prices started rising shortly after her father died. A decade ago Guiragossian’s works were selling for around $20,000-$25,000. In 2013, at Christie’s Dubai, his work La Lutte de l'Existence (1988) realised $605,000.

The foundation is now working with the families of two other Lebanese Modernists, Aref el Rayess (1928-2005) and Shafic Abboud (1926-2004), who have more recently started monitoring their works. In March, the family will publish the first Guiragossian monograph and a catalogue raisonné is in progress. While Guiragossian’s studio was bombed twice during conflicts in Lebanon, the family has been aided in authenticating his works by an unusually large number of records and photographs.

In one case, the foundation blocked a Christie’s sale of a Canadian woman’s painting, believing it was not genuine, although the owner was the wife of a well-known Lebanese former photographer who was Guiragossian’s friend. The work was only cleared after Manuella unearthed a photograph of it—marked with the photographer’s stamp—in a shoebox of papers belonging to her father.

Iraqi artists

Due to decades of conflict, Iraq is a particularly difficult case. Ahmed Naji, a London-based art historian, has been working to establish the archives of older living artists, as well as on the archive of Mohamed Makiya, the architect and first president of the Iraqi Fine Art Society. The planned book on Makiya would be the first on art patronage and collecting in Iraq, Naji says.

Anything that is only in the hands of government is not really protected. Family foundations are the last hope of preserving whatever is left of the country’s historyAhmed Naji

Irreplaceable records in Baghdad’s Centre for Contemporary Art, which was ransacked after the fall of Saddam Hussein, and in the Mosul Museum, whose collection was destroyed by Islamic State in 2015, have decimated the country’s art-historical narrative. “Anything that is only in the hands of government is not really protected,” Naji says. Family foundations, he thinks, are “the last hope of preserving whatever is left of the country’s history”.

Still, the withdrawal of a major work by Shakir Hassan al Said from Christie’s late last year (when a Paris dealer and then the artist’s son challenged the picture) shocked the work’s owner, the Iraqi artist Maysaloun Faraj. She helped to prevent a fraudulent work by Jewad Selim being sold at auction, she says.

The families of Selim and Jamil Hamoudi “have immense integrity, particularly in documenting/assessing/validating the work of their departed”, Faraj writes. However, she continues: “It is highly unfortunate that various others—be it artists’ families, so-called close friends or those who have appointed themselves as experts”—become involved. Some, Faraj thinks, are not driven by integrity alone and, she says, employing scientific analysis by independent experts is the costly, but far more reliable, option.