Her name was Gluck – no prefixes, suffixes or quotes allowed. Hannah Gluckstein (1895-1978) was born into a deeply conservative Jewish family with a vast business empire, mostly driven by the catering chain J. Lyons.

As a child, she was drawn to music and singing, but in adulthood painting became her true metier—it gave her an escape route, away from her claustrophobic family life in north London.

After attending St John’s Wood Art School, her parents allowed her to join a small artistic community in Lamorna, Cornwall, of which Alfred Munnings, Harold and Laura Knight, and Ernest and Dod Procter were a part. It was in Cornwall that Gluck’s true identity emerged. Her companion was a woman called Effie Craig, or simply Craig. Gluck’s dress became more masculine and her flowing, black hair was cut barber-short. She started to smoke a pipe.

Her first show of 56 paintings was at the Dorian Leigh Galleries in South Kensington in 1924. The business was owned by Gluck’s friend, the society photographer Emil Otto Hoppé, who not only admired her art but also her burgeoning sense of self. In his photograph of her, a fedora crowns her chiseled profile, accentuated by a jacket, stiff collar and tie. Gluck’s identity and her art had become inseparable.

Gluck: Lords and Ladies (1936) Private Collection

Gluck’s artistic centre was entirely her own. As a consequence, she always showed alone, and from 1926 exclusively at the Fine Art Society in London. There she cast herself as the stage manager of a multi-layered artistic production. In a 1932 show, her penetrating portraits and colourful still-lifes hung on cream walls painted to her precise instructions. Even the design and positioning of the characteristic three-tiered frames was her own.

That same year, she fell in love with the florist Constance Spry and, almost immediately, flowers took centre stage in her art. Sometimes the blooms were sexualised, with subtle yonic references; she later admitted to their complicated emblematic meaning.

Three years later, the affair with Spry gave way to perhaps the greatest love of her life, a rich married woman called Nesta Obermer. Despite its intensity, the affair was over in less than a decade, but Gluck immortalised it in a strident painting called Medallion. Like Gluck herself, this double portrait has become a totem of queer art.

The curators of Gluck: Art and Identity in Brighton have accepted the challenge of describing Gluck’s posthumous identity through her art and the wardrobe she left to the museum. Included in the show are love letters to Obermer and her last finished painting, a memento mori, dated around 1970-73, of a rotten fish head titled Credo (Rage, Rage Against the Dying of the Light).

• Gluck: Art and Identity, Brighton Museum and Art Gallery, until 11 March 2018

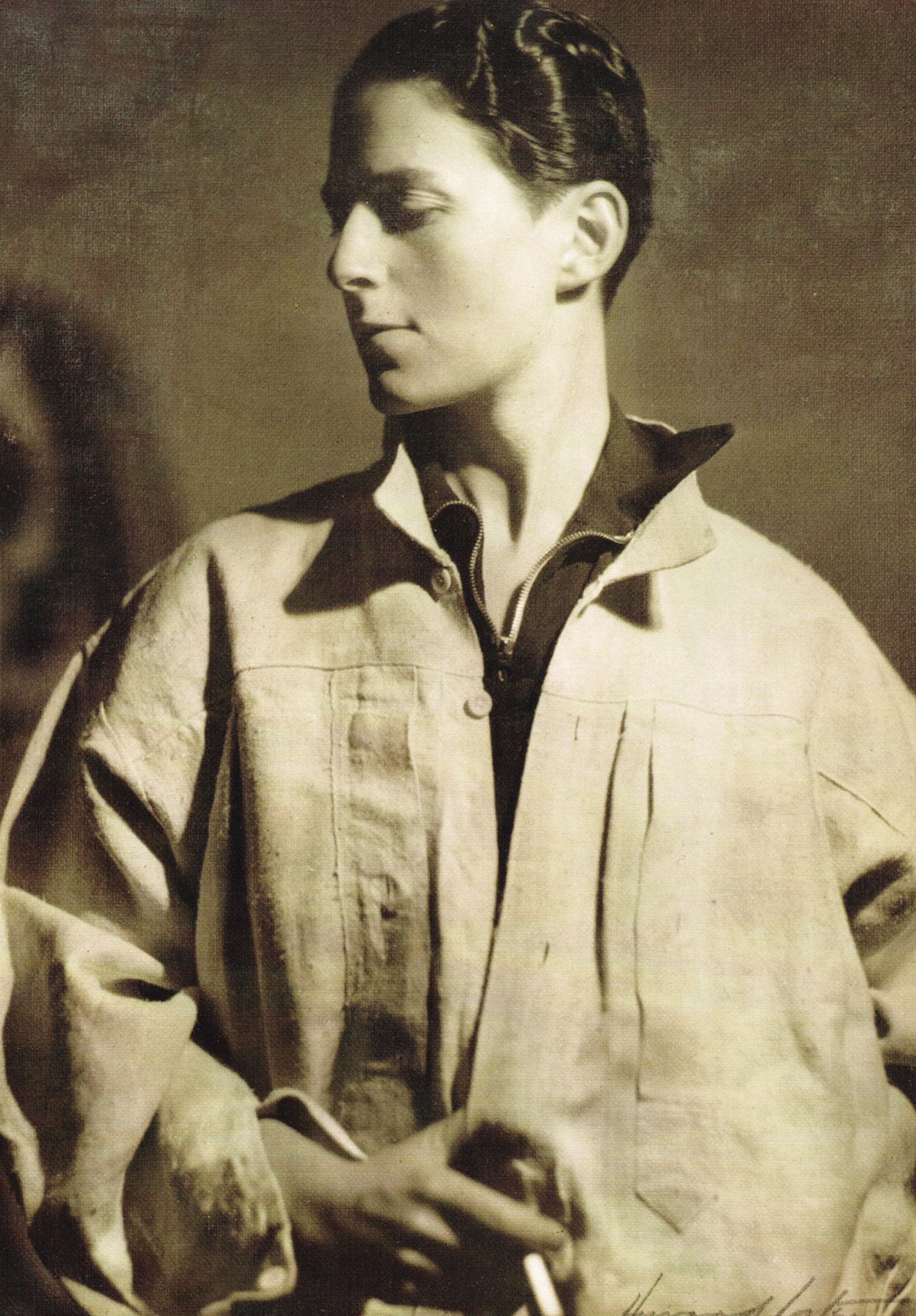

A 1932 photograph of the artist by Howard Coster Fine Arts Society