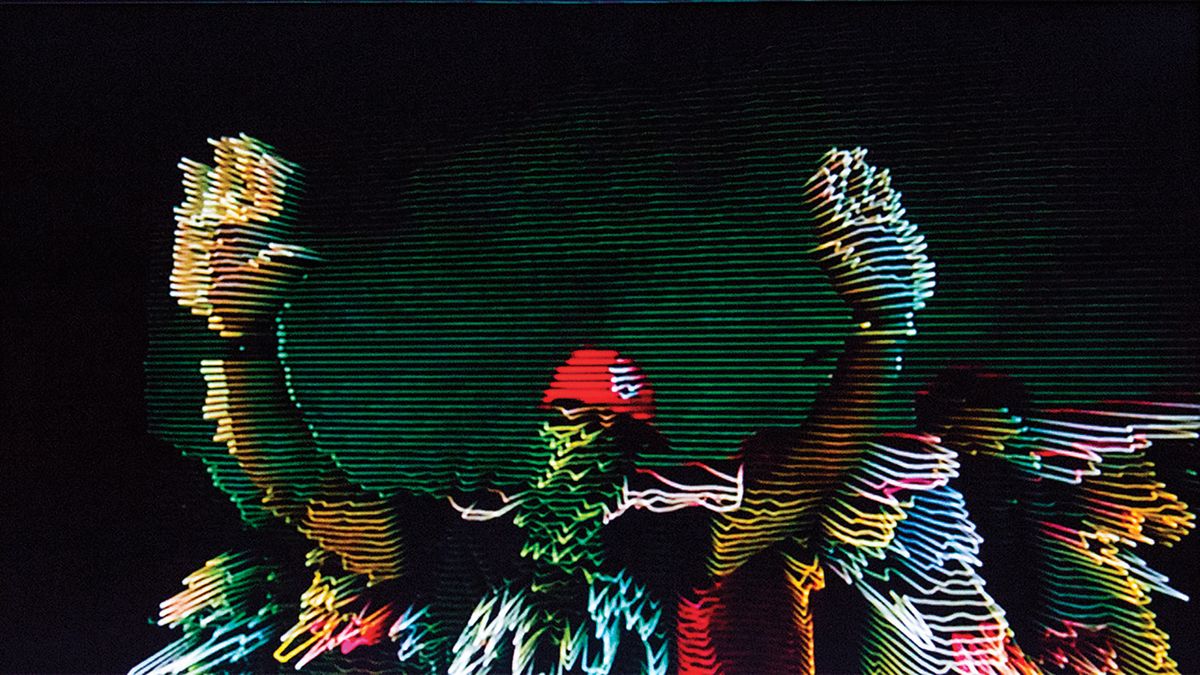

In 1994, the Korean-American artist Nam June Paik made Internet Dream, a “wall” of 52 television monitors playing a joyful patchwork of images. It was originally commissioned by the German broadcaster RTL, for its headquarters in Cologne. Twenty years later, HowDoYouSayYaminAfrican, a collective of artists and activists, began thewayblackmachine.net (ongoing since 2014). The work took the shooting of the African-American teenager Michael Brown by the white policeman Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, as a starting point. A series of screens and projections display images drawn from hashtags such as #Ferguson and #Blacklivesmatter.

These two installations open Art in the Age of the Internet: 1989 to Today. This exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), Boston, is one of the largest historical surveys of its kind to be mounted in the US. “I wanted to take a work which was about the ideal that the internet promised: democracy, dialogue, a platform in which ideas could be shared freely,” says the exhibition’s curator, Eva Respini. “Against that, I’ve set a work that is much more dystopian. The internet is divided: people live in algorithmic bubbles in which the internet supports and magnifies their existing beliefs. The two works set up the argument of the show.”

Camille Henrot, Grosse Fatigue (still), 2013 2016 ADAGP Camille Henrot; Courtesy of the artist, Silex Films and Kamel Mennour, Paris/London

Respini has brought together around 60 artists and collectives for the exhibition. Although the works have been made since 1989—the year the British scientist Tim Berners-Lee proposed the concept of the World Wide Web to his colleagues at research hub Cern—the artists involved span three generations, born between 1932 (Paik) and 1989 (Amalia Ulman). Several work in more traditional media, such as painting and sculpture. In this, and indeed in some of the key works, the exhibition mirrors Electronic Superhighway: 2016-1966, organised by Omar Kholeif at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 2016. That show was loosely arranged in reverse chronological order, while the ICA’s is organised into five “intergenerational” themes, including privacy and surveillance, the body, and the projection of the self in digital networks.

“Most shows in the US have focused on a generation of so-called post-internet artists,” Respini says. “I wanted to take a step back and look at some historical precedents. There are many artists who have been addressing the same themes.”

One of the highlights of the show will be a new virtual reality piece by the Canadian artist Jon Rafman, commissioned to work with the institution’s architecture. It “plunges the viewer into a virtual space”, in a gallery cantilevered over Boston harbour, Respini says.

The exhibition’s main supporter is the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and it is accompanied by an extensive catalogue, with essays by scholars and critics including Lauren Cornell and Tim Griffin.

• Art in the Age of the Internet: 1989 to Today, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, 7 February-20 May

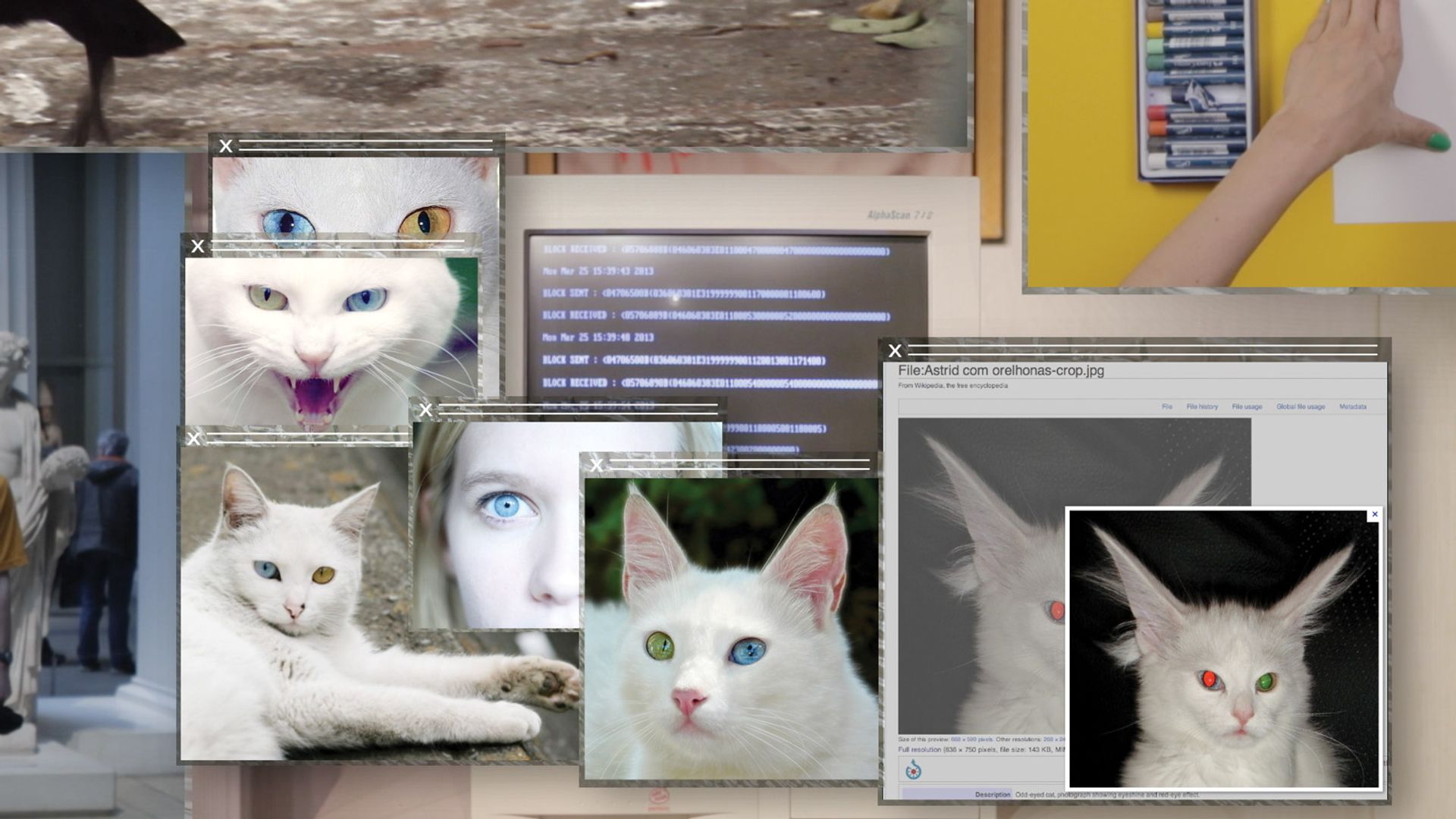

From the video My Generation (2010) by Eva and Franco Mattes Eva and Franco Mattes, My Generation, 2010. Installation view, Plugin, Basel

Artists nurtured in a digital age:

Omar Kholeif (who has also contributed to the catalogue for Art in the Age of the Internet: 1989 to Today) is working on another large-scale exhibition, this time for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. I Was Raised on the Internet (23 June-14 October) will show around 100 works made since 1989, many of them will be interactive and use virtual reality, gaming technologies and social media platforms. As well as works by artists such as Sophia Al-Maria and the duo Eva and Franco Mattes, it will include several new commissions, among which will be a multi-screen immersive film experience by the New York-based collective DIS.