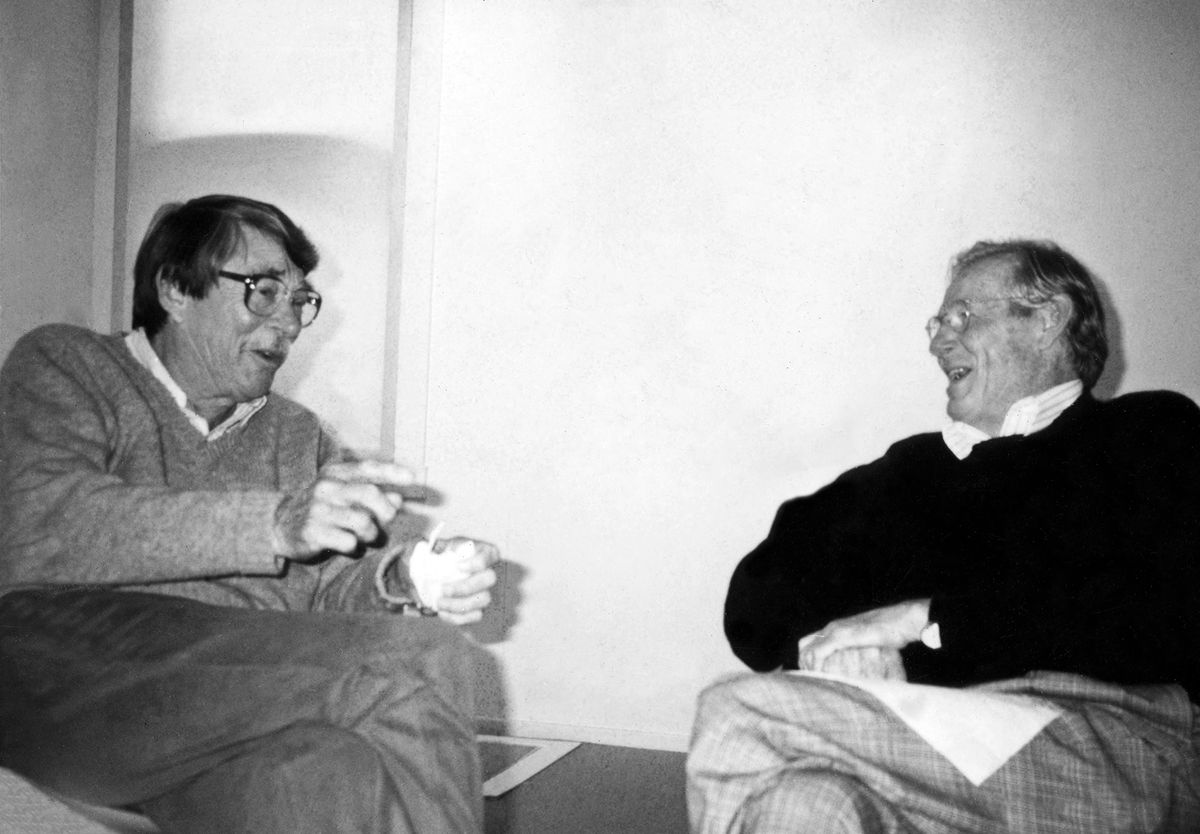

“We had wonderful conversations,” recalls the painter Wayne Thiebaud, aged 97, of his friend and fellow artist Richard Diebenkorn. Proof of that can be seen in a photograph of the two men laughing together, taken in 1991, two years before Diebenkorn’s death at age 71. “I miss him a great deal,” Thiebaud says, more than once. The image is reproduced on the wall of New York’s Acquavella Galleries at the start of California Landscapes: Wayne Thiebaud and Richard Diebenkorn (until 16 March), a show that not only draws on their artistic affinities, but reveals the deep, if somewhat lesser known, friendship between the painters.

When the two met in 1964, Diebenkorn was a prominent painter linked to San Francisco’s Bay Area Figurative group, which also included artists like David Park, who together had ruffled the New York critical establishment by embracing representational painting. As Diebenkorn declared at the time, abstraction had been “reduced to a book of rules”. But he returned to it eventually, and with a renewed vigour and sensitivity, for his career-defining Ocean Park series (1967-88), a cycle of flat geometric canvases that distilled the light and colour of Santa Monica, examples of which are on display at Acquavella.

Thiebaud was living in Sacramento in the mid-1960s, working as an art instructor at the University of California, Davis, and establishing himself as a scrupulous painter of common American confections—frosted cakes, pies, and ice creams—that viewers repeatedly mistook for the new Pop art, but which had altogether different aims. In the 1970s, Thiebaud started to paint landscapes in earnest, and was inspired in large part by the compositions and textures of Diebenkorn’s work.

Richard Diebenkorn, Berkeley #44 (1955) The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation. Private Collection

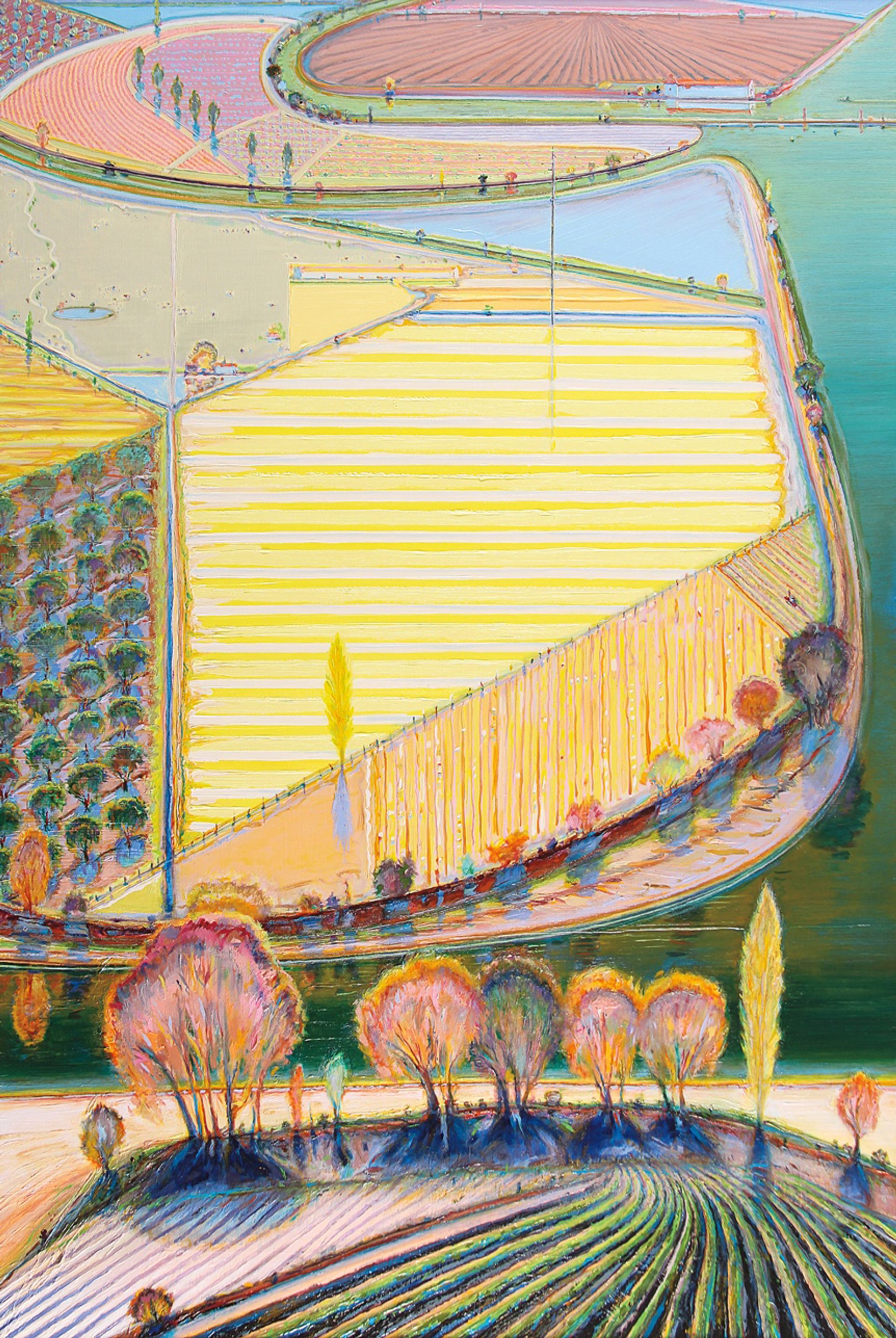

This exhibition is the first to unite the two painters’ landscapes. With around 20 objects that take as their starting point California’s topography, the show emphasises the artists’ shared strategies: verticality, gridded structures, aerial-like vantage points and a visible delight in the materiality of paint. But there are certainly differences. Diebenkorn’s blustery, highly abstract canvases are landscapes by feeling and suggestion, whereas Thiebaud explores illusion, finding a painterly order in the farms, fields, grooves and channels of the Sacramento Delta region, for example.

He renders this landscape with uncanny intensity. His Green River Lands (1998) is a disorienting compression of multiple vistas lifted and extended into one, and the light is not of this world, but like the unnatural blaze of some dream. Indeed, Thiebaud does not paint from life. “They’re all painted from memory,” he explains. “They’re constructed.”

Wayne Thiebaud, Green River Lands (1998) Wayne Thiebaud/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Collection of Matthew Bult

Landscape presents Thiebaud with an opportunity to explore formal questions, not necessarily the specificities of place. “The attempt is to express as effectively as I can a sense of equilibrium and disequilibrium, so that they are somewhat discomforting. Painting is a dead flat object and when you’re trying to get some tension, majesty, or ominousness, something has to happen within that structure, to entice people to it with their bodies physically, to experience it,” he says.

Like his friend Diebenkorn’s, Thiebaud’s landscapes were not initially well received by critics. “One, Lawrence Alloway, said I should burn the paintings and eat the ashes and never paint again,” he recalls. “He was very disappointed because he had been rather affectionate of the earlier food works.”

Of course, he continued to paint landscape. Some of the works are dated as recently as last year, and they demonstrate that, at least on canvas, Thiebaud continues to have those conversations with his friend.