By many estimates, as much as two-thirds of the oeuvre of the Old Masters—artists like Leonardo, Michelangelo and Titian—is considered lost. Many of those works are known through archival material and primary source documents, and yet we have no idea where they are.

Some of the lost works were more influential to history and art than the works that do survive by these artists. And yet, when we study art history, we tend to teach the same core of several-hundred objects that are all extant. This is understandable, since it is easier to teach something that one can visit. But archaeologists study that which is lost, or in such ruin that it must be reconstructed with the imagination or digital technology. Why do we rarely do this with art?

Learning the story of some of these important missing pieces illuminates the shadowy ancillary chapels of art history, painting a negative-space portrait of that which is familiar. It is easy to imagine a survey of Western art history course taught exclusively through important lost works. It also underscores the preciousness of that which we still possess, which we can visit and which, all too often, we take for granted.

This series will examine important lost works, considering both their influence on history and the story of art, but also their “biography” as an object—how they were lost, and why.

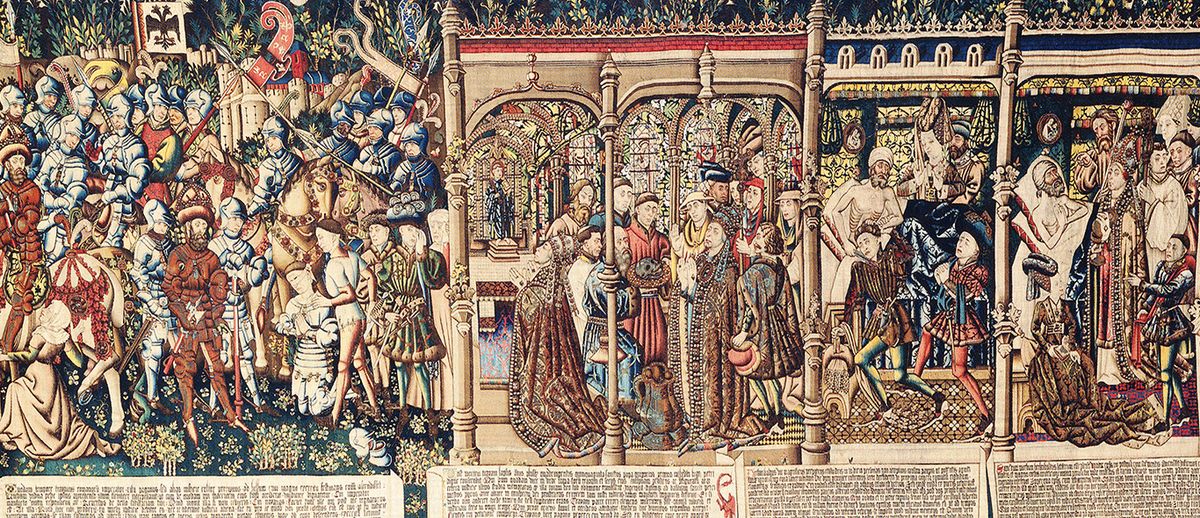

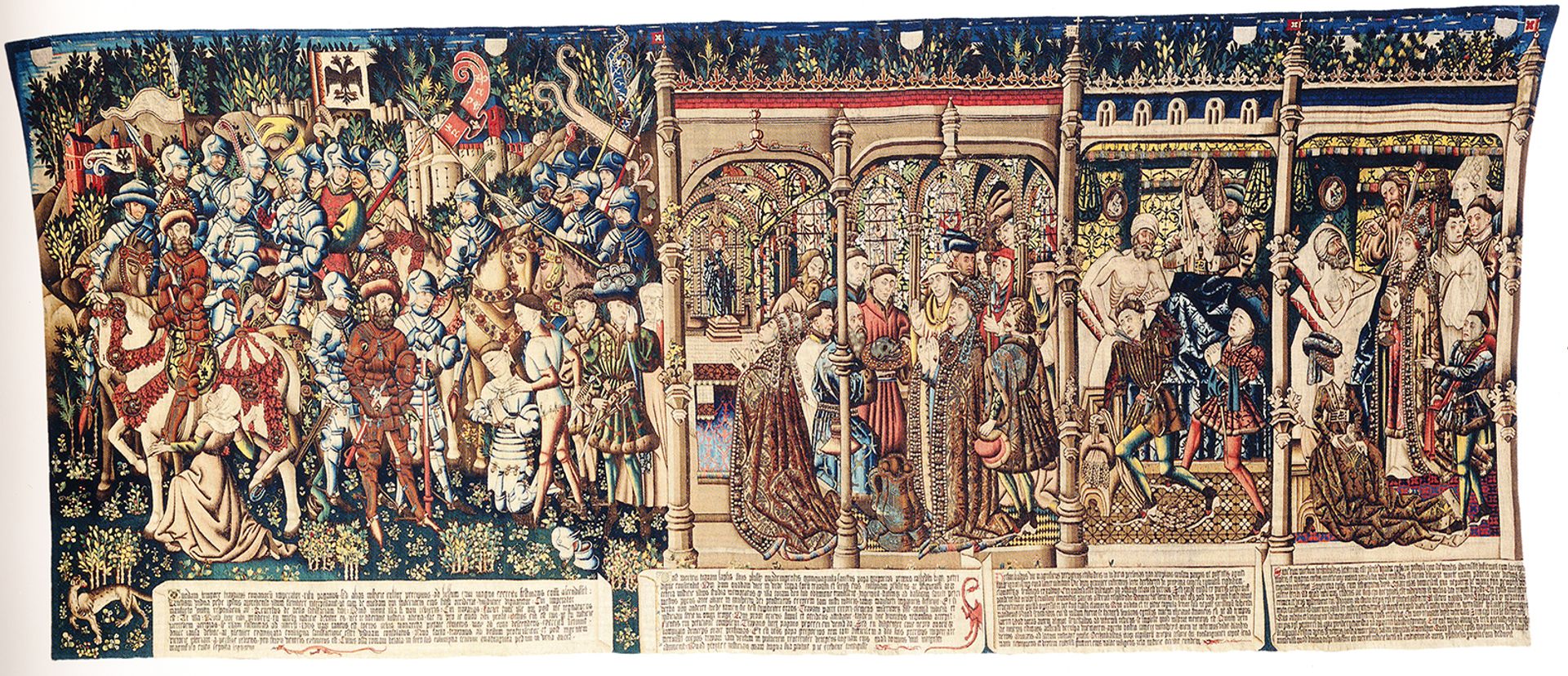

A tapestry copy of The Justice of Trajan and Herkinbald now in the Historical Museum of Bern

Rogier van der Weyden’s The Justice of Trajan and Herkinbald in the Golden Chamber (around 1435-50)

We know precious little about the life of Rogier van der Weyden, one of the most influential and greatest painters of that cradle of the Renaissance, mid-15th-century Flanders. The archives of Rogier’s native city of Tournai were completely destroyed during the Second World War and, with them, the secrets of the painter’s early life and work. Some archival material had been partially transcribed in the 19th century, and it is from these fragments that we know as much as we do about the man called “Maistre Rogier de le Pasture”, who would later change his name to the more Dutch Rogier van der Weyden.

During Rogier’s lifetime, his most famous and important work by far was a series of four colossal paintings, each on the theme of justice, commissioned for the Gulden Camere (Golden Chamber) of the Brussels City Hall. Unusually, two of the four works on panel, both dated to 1439, were signed (a practice that was not regular for painters until the 19th century, but which Rogier and his contemporary, Jan van Eyck, practiced on occasion). The other two panels were likely painted later, but all were complete and in place by 1450.

Alas, the bombardment of Brussels by French troops during the Nine Years’ War (August 13-15, 1695) and the subsequent fire that raged through the city obliterated all four of them (along with a third of the city’s buildings), and they “survive” only through numerous descriptions by visitors and writers who admired them—including Albrecht Dürer, who in 1520 made a special point of visiting city hall in order to see them—as well as several copies in drawings, paintings and tapestry. The tapestry illustrated above, now in the Historical Museum of Bern, represents the most intact and complete indication of how the paintings looked, even including inscriptions along the edges that are thought to have originally been carved into the framework of the panels.

A diptych of The Justice of Emperor III by Dieric Bouts the Elder

The paintings were each around 12 feet high, and the four panels spanned some 35 feet across, which is absolutely enormous, a size to rival frescos. Their subjects were meant to provide a moral example to the judges of the Golden Chamber, demonstrating the exemplary moderation of justice by the Roman emperor Trajan and the rather vigilante version dealt by the mythical Duke Herkinbald of Brabant. It was en vogue to commission paintings of famous scenes of justice being fairly meted out in Flemish civic buildings, and other examples did survive the trials of time: Dieric Bouts decorated the town hall of Louvain with Justice of Emperor Otto III, while Gerard David’s Justice of Cambyses looked down upon the chamber of the aldermen in Bruges—a particularly gruesome scene of the live flaying of a corrupt judge, which is difficult to look at today. But in the current political climate, where injustice is a frequently resonant theme, the scenes of Van der Weyden’s cycle feel, unfortunately, relevant.

The first panel of Rogier’s Justice Cycle shows Emperor Trajan, mounted on a steed and ready to set off to battle the Dacians. A peasant woman stops his horse and demands justice for the death of her son at the hands of one of Trajan’s soldiers. In the same panel, we see the murderous soldier beheaded, while Trajan and his nobles look on (as does an anachronistic Franciscan monk). The tale comes from the 13th century Alphabetum Narrationum by Etienne de Besancon, though in the original Trajan offers the old woman his own son in exchange for her murdered child.

The second panel shows Pope Gregory praying before Trajan’s Column; then examining the skull of Trajan in the presence of a bevy of cardinals, while a doctor points to Trajan’s tongue, which is miraculously still intact and ready to resume pronouncing fair sentences. Like the incorruptible bodies of dead saints, the emperor’s “sanctified” ability to deal justice never dies. The third panel shows a legendary Duke of Brabant, Herkinbald, as he lies ill in bed. We then see him suddenly rise and slit the throat of his evil nephew, whom he has summoned to his bedside. The nephew had committed a rape that the good duke felt would otherwise go unpunished in a more traditional trial. Another section of the panel shows the witnesses to this private execution, including the painter himself. The fourth panel likewise features Herkinbald in bed, while a bishop ministers to him before a huge crowd. The duke miraculously received the Host, despite the fact that he did not confess to the murder of his nephew, because he felt it was a just killing, not sinful. God, it seems, agreed.

The central panel of Jan van Eyck’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb

The scale, number of figures, and formal, if not conceptual, complexity place this work alongside van Eyck’s Adoration of the Mystic Lamb among the crown jewels of Flemish painting from the mid-15th century. Contemporaries certainly thought that they were on the same level, and intellectual travelers from across Europe sought out both out. The Mystic Lamb survives to this day, despite all manner of hazards that have threatened it—fire, theft, iconoclasm, looting, rogue vicars, dismemberment and more—while the bombs and blazes of the Nine Years’ War laid waste to Brussels and the pinnacle of Rogier’s career.

It is sobering to consider how many masterpieces by renowned artists we have lost. Rogier is now best-known for his Deposition at the Prado in Madrid, but during his lifetime, his Justice Cycle was his calling card, and was a destination work for pilgrims of art and culture. It is easy to forget that works that survive, and that we associate with great artists, were not necessarily their greatest, most influential creations—they are just the ones that happen to have survived, winning the dice-roll of history.

• Noah Charney is a professor of art history and the author of Stealing the Mystic Lamb: the True Story of the World’s Most Coveted Painting