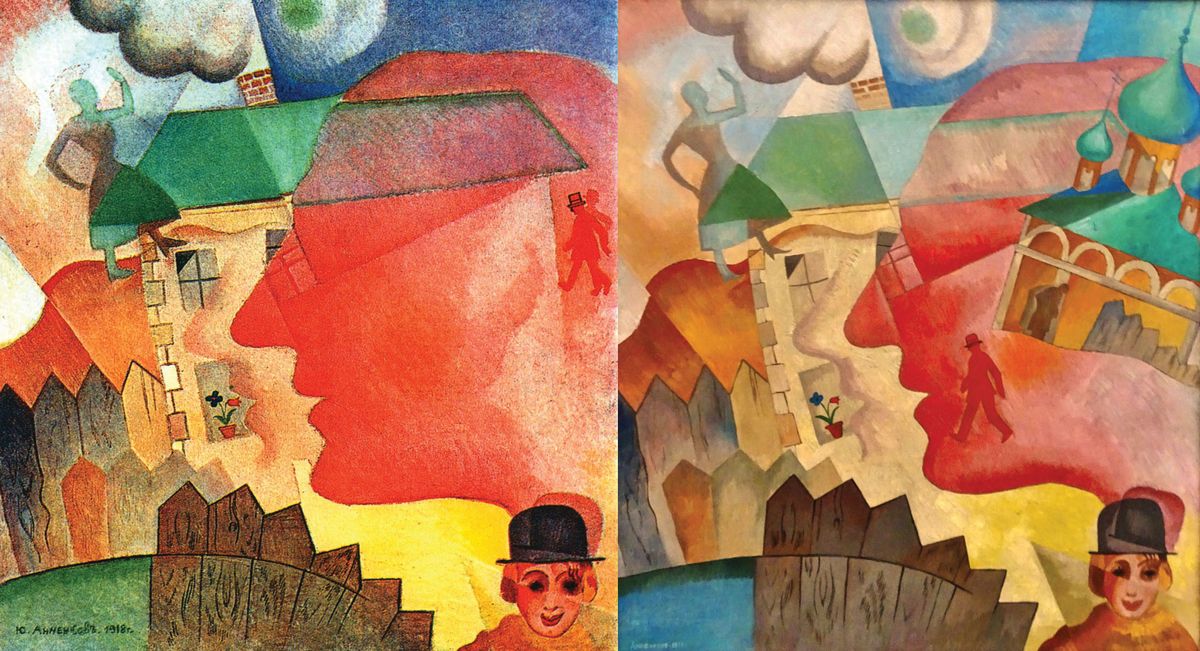

In a shock U-turn on 29 January—the day our article was published in the February issue of The Art Newspaper—all 24 Russian avant-garde works loaned by the Dieleghem Foundation to the Museum voor Schone Kunsten (MSK) in Ghent were removed and placed in museum storage.

When the works’ authenticity was first publicly questioned by ten dealers, curators and art historians in an open letter released on 15 January, the museum’s initial response—at the prompting of Flemish Culture Minister Sven Gatz—was to announce the creation of an "expert committee" to examine half-a-dozen works, with all the others remaining on display until the committee’s findings (slated for the end of February) were released.

But a museum statement issued (in Flemish) at 17:10 on January 29 – four hours after Flemish Culture Minister Sven Gatz was forwarded a copy of The Art Newspaper’s 3,000-word exposé – acknowledged that, because "discussion of the authenticity of the Toporovskys’ collection has taken on great proportions", the committee would now be granted "unlimited access to all works... so that research can be conducted smoothly and in complete serenity".

Here is our article in full:

On 20 October 2017, a display entitled Russian Modernism 1910-30 opened at the Museum voor Schone Kunsten (MSK) in Ghent, Belgium. It consists of 24 works attributed to Larionov, Goncharova, Tatlin, Filonov, Kandinsky, Malevich, El Lissitzky, Exter, Popova, Rozanova, Rodchenko, Udaltsova and others. The provenance of all of the works is given as the Dieleghem Foundation, which was set up by the Russian Igor Toporovsky and his wife, Olga.

On 15 January, an open letter was published in the Flemish daily newspaper De Standaard, signed by ten art-world figures with specialist knowledge of the Russian avant-garde, describing the works on show in Ghent as “highly questionable” and calling for them to be taken down pending further research. Among the signatories are the dealers Julian Barran, James Butterwick, Richard Nagy, Ivor Braka and Jacques de la Béraudière, and curators and collectors including Natalia Murray, the co-curator of the 2017 exhibition Revolution: Russian Art 1917-32 at London’s Royal Academy of Arts, and Alex Lachmann, a regular presence at London’s Russian art sales and one of the biggest hitters in the field. The letter goes on to say: “They have no exhibition history, have never been reproduced in serious scholarly publications and have no traceable sales records.” The museum “did not provide any information about their provenance or exhibition history…other than the name of the owner”.

The Russian avant-garde quickly became a popular vehicle for investment

This prompted an early-morning crisis meeting at MSK. Museum staff were told not to comment on the affair. At 3.30pm, a statement was issued declaring that the institution had assessed the loans on the basis of “confidential information from the collector” and that “the documentation folders and the descriptions in the possession of the Dieleghem Foundation provide a background to the history and authenticity of each of the works”. None of this background material has been released.

The statement, drafted at the initiative of the Flemish culture minister, Sven Gatz, also announced that a committee of experts would be established “to further research the Russian artworks currently on view at the MSK”. It concluded with the unsubstantiated assertion by Ghent’s alderwoman for culture, Annelies Storms, that the museum had “unintentionally ended up in a debate between art dealers and merchants, most of whom also have a financial interest in the matter”.

Storms’s allegation riled four of the letter’s signatories: Konstantin Akinsha, Vivian Barnett, Natalia Murray and Alexandra Shatskikh, who are all academics and/or curators. Speaking on their joint behalf, Akinsha tells us that they will be responding after taking legal advice.

Although Gatz had first advised the owners of the Russian works to approach the museum, he was now doing his best to distance himself from the affair. “In our country, directors and curators are responsible for what their museums exhibit,” he told De Standaard.

On 18 January, after a new article in De Standaard revealed that the director of Luxembourg’s National Museum of History of Art, Michel Polfer, had also been approached by the owners but “received no assurances about the works’ provenance or how they entered Belgium”, Gatz ordered that the Ghent pictures undergo laboratory analysis.

The director of MSK, Catherine de Zegher, refused to speak to The Art Newspaper, but referred us to the Toporovskys, who say that they are “open to analysis and discussion” of their works, and that “experts can come and consult our archives, look, and give a public and scientifically justified opinion”.

Catherine de Zegher with Igor Toporovsky Fondation Dieleghem

Igor and Olga met at Moscow University, where they were both history students. After graduating in 1988, Toporovsky says he joined the European Institute think-tank recently launched by the future Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev and “helped arrange his visit to the Vatican” in 1989. He then worked as an “independent consultant” for another Russian president, Boris Yeltsin, and was also in charge of Russian MPs’ visits to Europe, the United Nations and Nato, meeting the former European Union president Jacques Delors along the way.

Toporovsky stood unsuccessfully for the Russian parliament as an independent in 1995, and was axed as a Yabloko party candidate before the 1999 elections for not submitting the necessary documentation. According to Russian tax records, he was registered as an employee of the presidential administration from 2003 to 2006, although the only taxable income he declared was payments from the culture ministry for the last five months of 2005.

After The Art Newspaper Russia published an article including material on Igor Toporovsky’s time in Russia, we asked the couple for their reaction. “The author will be prosecuted,” Olga said. Igor added: “The article is largely unfounded. It is defamatory in every detail.”

In 2006, the Toporovskys left Moscow for Brussels in the wake of a “disagreement” with Vladimir Putin’s administration. A member of Russia’s art-crime squad from 2002 to 2008 offers a different perspective, however. The former prosecuting lawyer Nikita Semyonov came across Toporovsky while investigating the so-called Preobrazhensky Affair in 2005 and 2006; this led to the conviction of Igor and Tatiana Preobrazhensky, who ran the Kollektsia Gallery in Moscow, for selling fake Russian paintings. During the course of this investigation, Semyonov says, the police found a handwritten receipt for almost $3m, signed by Toporovsky, for two paintings by Malevich and Kandinsky that the Preobrazhenskys had sold on his behalf to a “powerful oligarch”.

“When we began to verify their provenance, we had doubts about their authenticity,” Semyonov says. Toporovsky said that the works came from the family of Iosef Orbeli, the director of St Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum from 1934 to 1951, through a certain Camo Manukyan. The unnamed oligarch did not collaborate with the investigators or allow the paintings to be examined. Toporovsky “emigrated from Russia shortly after the interrogation”, Semyonov says. When we asked him what he remembered of the Preobrazhensky Affair, Toporovsky said: “I visited the gallery once; I had some information about the affair, but with many gaps and imprecisions.”

Semyonov, who now works as an art consultant and legal adviser, encountered Toporovsky’s name again in 2013, when he was approached by an artist claiming to have sold around 50 paintings “in the style of Russian avant-garde artists”, each priced at around €1,500, to Toporovsky and a Russian dealer with galleries in Paris and New York. When the dealer refused to pay, Semyonov says, the artist went to the police, providing them with photographs of the works. “Comparing the photos of these paintings with photographs from the Ghent exhibition, I can see similarities,” Semyonov says.

In 2009, Toporovsky lent several works to the exhibition Alexandra Exter and Friends in Tours, France. This was closed down by police, who impounded a number of works suspected of being fakes. A court cleared Toporovsky of suspicion and his works were returned.

In 2017, the Toporovskys registered a foundation in Belgium called Dieleghem, after the Château de Dieleghem, which they own and aim to turn into a museum to house their collection by 2020. The foundation’s declared goal is the “disinterested promotion of works and artists of European art from the period 1850-1930 and Russian Modernism 1900-30”, but it reserves the right to sell “any element it owns if it does not fit into the collection as defined by the founder”. The collection consists of around 500 works, two-thirds of which are paintings.

Toporovsky says that he decided to show some of the works at MSK “so as not to lose time. We approached several museums in Belgium—La Boverie in Liège, the Musée d’Ixelles and Bozar in Brussels—then I talked to the Flemish culture minister, Sven Gatz, about what we could do. Antwerp is the biggest Flemish museum, but still under restoration; that left Ghent, so I contacted Catherine de Zegher.” De Zegher is not a specialist in Russian Modernist art but she was the curator of the 2013 Moscow Contemporary Art Biennale. Nonetheless, the works on show at MSK were selected jointly with De Zegher, Toporovsky says.

The case of the altered exhibition catalogue

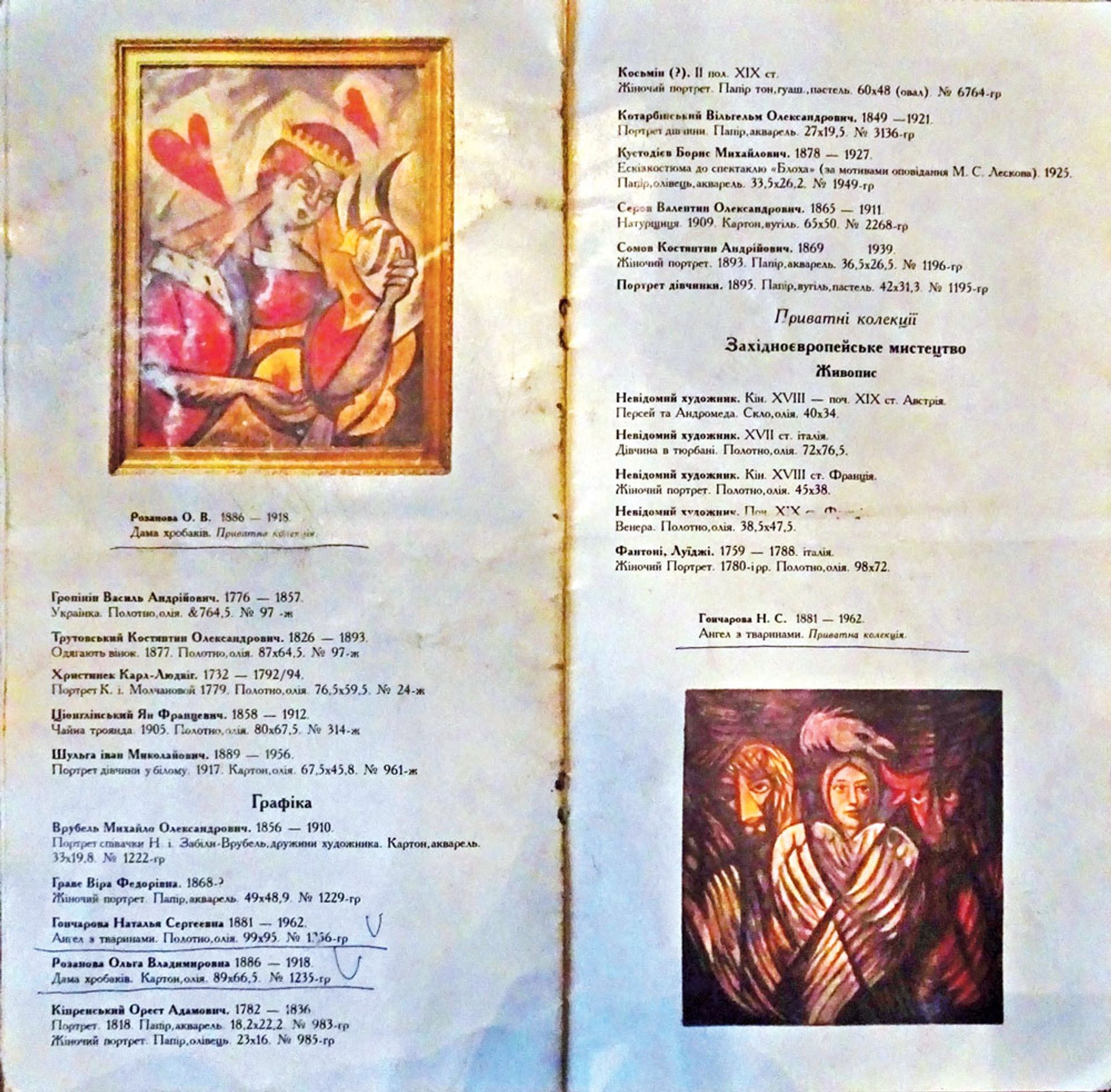

The Goncharova Evangelists reproduced in the ‘1992’ catalogue and listed under "Graphics" Dieleghem Foundation

The Toporovskys have explained the history of the undated Goncharova Evangelists, which are on show in Ghent, by producing the well-worn catalogue to an exhibition called Beautiful Image, staged by the Kharkov Art Museum/Kharkov Collectors’ Club, and dated 1992. It reproduces the Evangelists with a caption that translates as “N.S. Goncharova, Angel with Creatures, private collection”. But Valentina Myzgina, the director of the Kharkov Art Museum since 1993 and an employee of the institution since 1970, says that the show never happened. She says that the document is a reworking of a catalogue from 1998. The Kramskoy portrait on the 1998 cover has been replaced, and the year altered from 1998 to 1992. “Neither the Goncharova nor the Rozanova on the opposite page were in the 1998 show,” Myzgina says. She says that the two pages concerned have been doctored, the images replaced and part of the text altered. She also says that, although the works are paintings, the “1992” catalogue lists them under “graphics”, with “false museum inventory numbers with the cipher GR used for graphic works”: N° 1256-GR for the Goncharova and N° 1235-GR for the Rozanova. Myzgina says that the Goncharova is captioned “private collection”, yet “items entering the museum temporarily do not receive inventory numbers”. When asked to comment on the allegation that their catalogue is a fake, Olga Toporovskaya referred to it as “material proof”, adding: "Since 1991-93, 27 years have passed. I think that the [Museum] Director has also changed."

The authentic 1998 catalogue Kharkov Art Museum

The Toporovskys’ claims examined

The Museum voor Schone Kunsten (MSK) plans a show of works from the Dieleghem Foundation on the spirituality of Russian Modernism in 2019, with loans from other European institutions “such as the Ludwig Museum”. Toporovsky says that the scholars Magdalena Dabrowska and Noemi Smolik will be involved.

Dabrowska says that she has met the Toporovskys in Brussels but “will not be involved in any capacity. As a scholar of a given period, you don’t walk into a house filled with works of that period, never seen, published or reproduced before, without asking yourself ‘why?’ and ‘where do they come from?’”

Noemi Smolik was equally indignant to see her name cited in this context, and told The Art Newspaper she was "in no way involved in any activity of the Dieleghem Foundation," explaining: "After seeing the exhibited works in the Museum and the works in the Toporovskys' house in Brussels, and after examining some of the facts about the works' provenance that I had been given by Mr Toporovsky, I made the only possible decision: fake."

When we asked him how the works left Russia for Belgium, Toporovsky said they “were stored in Ukraine and the Baltic states, where I have always had family”. (He was born in Dnipro, Ukraine, and says he has longstanding family ties in Latvia.) Asked if export permission had been an issue, he declined to comment.

Exporting cultural goods from Ukraine is at least as complex as it is from Russia, and Latvia also requires export permits to Belgium, despite being a fellow member of the European Union.

A wall panel at MSK declares that the Dieleghem Foundation’s collection is “closely associated” with Antoine Pevsner and his brother Naum, better known as Naum Gabo. Olga Toporovskaya says that “Antoine and Naum had a brother who lived in Leningrad; my great-grandfather was a cousin.” She says that her great-grandfather acquired the avant-garde works owned by Naum and Antoine after moving to Moscow, which the brothers left in 1922/23.

Naum Gabo’s daughter Nina tells The Art Newspaper that she has “never heard of Olga Toporovskaya” and that, as far as she is aware, Naum Gabo did not leave a collection of Russian avant-garde art in Russia.

Toporovskaya says her father got to know George Costakis, the celebrated Greek collector of avant-garde art, in Moscow in around 1952, when her father was just 15, and that, when her father was later on the board of the International Philatelist Committee, he exchanged drawings with a Pevsner provenance for philatelic materials from Costakis. Toporovskaya adds that her father also acquired a “couple of pictures” from the widow of the artist Alexander Kuprin, and bought the archives of the actor Mikhail Astangov, which included the Tatlin nude on show in Ghent.

Aliki Costakis, George’s daughter, says that she does not know of any Olga Toporovskaya, nor has she heard about any co-operation between their fathers. Olga says the fact that Gabo’s and Costakis’s daughters “are not aware of my existence… does not prove that my father didn’t know Costakis and didn’t exchange [the drawings] with him”.

Toporovsky says that he began to buy paintings in the early 1990s. One source, he says, was Camo Manukyan, who, he claims, came to Moscow with avant-garde works that his uncle, Iosef Orbeli, the director of the State Hermitage Museum from 1934 to 1951, had saved from Stalinist destruction by sending to Armenia. Manukyan, Toporovski says, sold the Ace of Clubs by Ivan Puny to the State Tretyakov Gallery and a Lentulov to the oligarch collector Piotr Aven.

Andrei Sarabyanov, a leading Russian expert on the Russian avant-garde, is sceptical about the idea of a museum director being able to sneak works out of his museum and secretly dispatch them from Leningrad to Erevan, the capital of Armenia. “If this had happened, the museum leadership would have been arrested immediately,” he says. It should also be noted that Iosef Orbeli was a scholar in the field of antiquities before becoming the Hermitage’s director.

Toporovsky says that after buying a Rodchenko (not in the Ghent show) from the Moscow auction firm Alfa-Art in 1993, he established links with Manukyan and was able to buy “a good part” of the Orbeli collection.

Maxim Boxer, a board member of the Russian art dealers’ federation, the International Confederation of Antiquaries and Art Dealers, was an expert at Alfa-Art in 1993. He remembers Manukyan because he “regularly visited our auction house. But by 1994, we had begun to have serious doubts about the works he offered us for sale, and we ceased to deal with him.” The Toporovskys say that the Dieleghem Foundation “would like to produce a publication on the Orbeli collection, a very important part of our holdings, with an article about its history written by Manukyan”.

Orbeli’s daughter-in-law, Tatiana, tells The Art Newspaper Russia that he never had a private collection. “He did not even have a home,” she says. Marina Bunatyan, the director of the Orbeli Brothers Museum in Tsaghkadzor (near Erevan), which she co-founded in 1982, says: “I know all Iosef Orbeli’s descendants and have talked to them countless times, but I have never heard this story.”

The provenance of four works in the Ghent show—Woodcutters (1912) and Suprematist Composition (1922/23) by Malevich, a Rodchenko constructivist composition and a 1917 Kandinsky composition—is given as the State Committee for the Arts, but no such body appears to have existed, although there was an arts committee of the USSR Council of People’s Commissars, renamed the Arts Committee of the USSR Council of Ministers in 1946. It was disbanded in 1953 and its operations transferred to the ministry of culture. Its archives can be consulted in the Russian State Archive of Literature and Arts in Moscow.

The art historian Konstantin Akinsha, who has worked extensively on the archives, says: “There is no information about sales of avant-garde works from Soviet museum collections being authorised by this arts committee either before or after 1946. Anyone brave enough to claim such a provenance needs to provide documentary proof.”

Toporovsky talks of other sources for the works, mainly “museum stores outside the USSR”. There were “two types of store: those in republics outside what is now the Russian Federation—Ukraine, Belarus, Uzbekistan etc—and, above all, the stores administered by the defence ministry and the KGB”. He says that Lenin’s commissar for education, Anatoly Lunacharsky, created a museum network across Russia showing Modernist and other works, but “all were abolished by Stalin, and some works were burned or disappeared. Others were stored away by the services in charge of the liquidation, the military and the KGB.”

Alfa-Art’s founder, Mikhail Kamensky, the head of Sotheby’s Russia from 2007 to 2016, says: “The idea that the KGB created a secret fund to store the works of Russian avant-garde artists is ridiculous, and the idea that the ministry of defence controlled or created specially designated stores with paintings of avant-garde artists is totally absurd. The military never interfered with the inner life of Soviet art museums—they simply didn’t care. Ideology was not their field.”

Igor Toporovsky TELLS The Art Newspaper that he started buying Russian Modernist works in the early 1990s, when he was “almost alone” in the field, and able to buy such works “because I was working in the political world and had insider contacts. The prices were extremely low.”

Kamensky is adamant that “the hunt for masterpieces started in the 1970s following the fame of George Costakis. The Russian avant-garde quickly became a popular vehicle for investment”.

Experts comment on other works

The Rozanova 1915 Futurist composition features a scarlet 25-kopeck stamp with the profile of Tsar Nicholas II ringed by the Cyrillic inscription “Pochta Rossiiskoy Imperii” (post of the Russian Empire), but Nicholas II’s head never appeared on 25-kopeck stamps. His profile was used only on coins, and the inscription was never used, either.

Detail of a “Rozanova” 1915 Futurist Compositon featuring a scarlet 25-kopeck stamp with the profile of Tsar Nicholas II ringed by the Cyrillic inscription Pochta Dieleghem Foundation

A Mountainscape ascribed to Roerich is entitled Tibet and dated 1922, a year Roerich spent entirely in the US. Kenneth Archer, the author of Roerich East and West (1999), confirms that Roerich did not set eyes on the Himalayas before the end of 1923, did not paint any known views of the Himalayas before 1924, did not set foot in Tibet until 1927 and listed all the paintings he executed there in his travel diary Altai-Himalaya (1929). Archer has never seen this painting nor any reproduction of it. “It does look rather suspect to me,” he says, “as if some other artist may have compiled it more recently by incorporating features from authentic Roerich works and adding various features of his own.”

A Mountainscape ascribed to Roerich in the Ghent show Dieleghem Foundation

Willem Jan Renders, the curator of Russian art at the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, and secretary of the Lissitzky Foundation, tells The Art Newspaper: “The two works supposedly by Lissitzky in the Ghent show resemble two well-known Proun paintings: Proun P23 n°6, in the collection of the Van Abbemuseum, and Proun GBA, created in 1923, in the Gemeentemuseum, the Hague. Both are well documented and we believe they were painted by El Lissitzky. Seeing these two paintings now in Ghent, many questions arise. Why would Lissitzky have painted a different version of these two works? And why would he do so in a different format? In our archives, there is no historic photograph or description of the Ghent paintings. So why were they never published? Moreover, has there been chemical analysis or x-ray examination of them? Until these questions are answered satisfactorily, the two works in Ghent will remain highly questionable.”

UPDATE: This article was updated on 1 February to include Noemi Smolik's comment.