When art market money talks these days, it says in effect that Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-88) “is one of the most significant painters of the 20th century”. But this statement, or overstatement, by Jane Alison happens to appear in the foreword for the useful catalogue of the exhibition Jean-Michel Basquiat: Boom for Real (until 28 January) at the Barbican Art Gallery.

The show, a collaboration with the Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, aroused high interest in London, symbolised by the appearance, just before its opening, of a Banksy outdoor wall piece on an adjacent pedestrian underpass. The image described a scarecrow-like Basquiat-style figure being frisked by armed security personnel, a Keith Haring-esque figure hovering to one side, holding Basquiat’s graffito three-pointed crown.

The exhibition assembles the largest selection of Basquiat’s work ever brought before a European public, and it challenges visitors to sort out their responses to the various powers of art market clout, of cultural myth and of an individual creative force. “It might be all too tempting to mythologise Basquiat as the Jimi Hendrix of the art world,” Dieter Buchhart writes in the exhibition catalogue. “But what does it matter in the end how early, how fast and in what quantity an artist’s work was produced?”

Visitors looking at Jean-Michel Basquiat's Ishtar (1983) in Basquiat: Boom For Real at the Barbican Art Gallery, London Tristan Fewings / Getty Images

Those are precisely the questions no inquisitive visitor to the exhibition can avoid, and which the project seemingly attempts to muffle. Many people will enter the show aware that posthumously the market for Basquiat's work has exploded. Paintings by him have left the auction block for prices as high as $120m.

The artists and director Julian Schnabel, a highly successful manager of his own art-world persona, made an affecting bio-pic, Basquiat, of his younger friend’s truncated career, with Jeffrey Wright in the title role. But countless people who have never seen the film will already know that Basquiat died of a drug overdose at 27, leaving his work burning with youthful energy but in critical limbo. Those who never knew the artist—me included—cannot but scan his work and his aggressively promoted career for omens of early burnout.

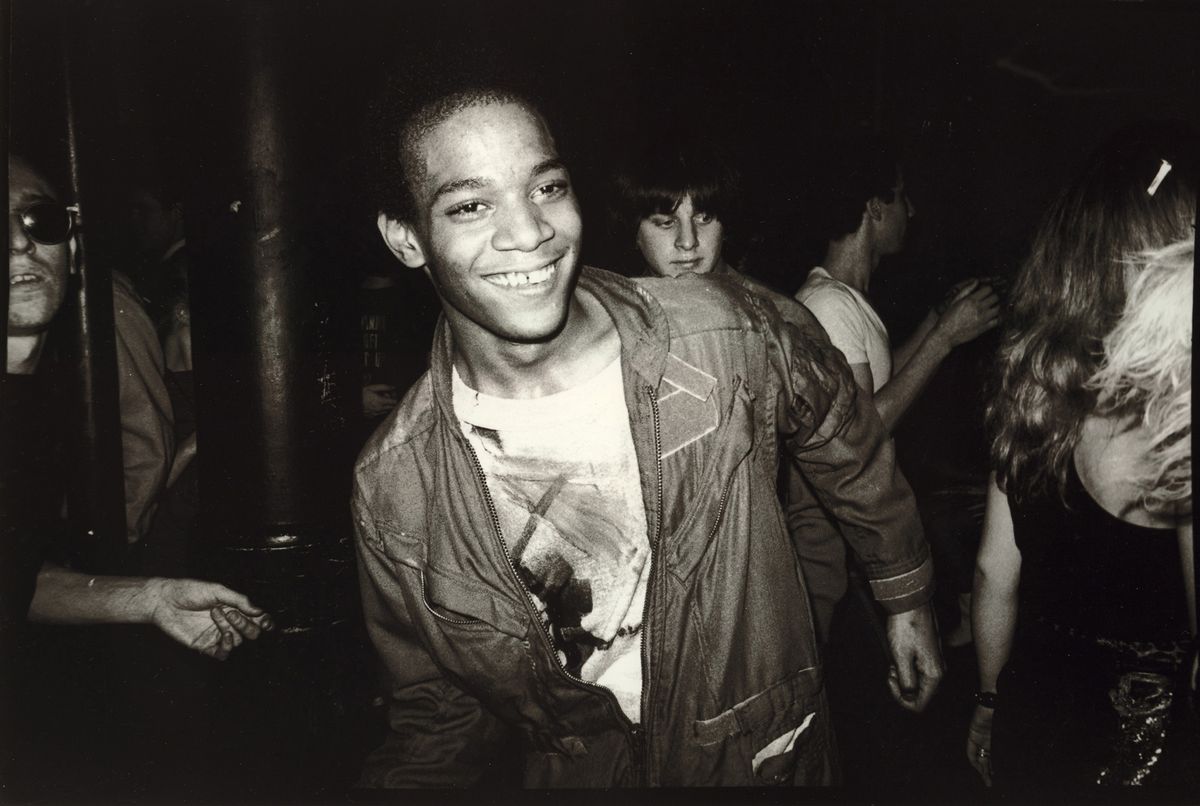

Basquiat stepped into multiple roles prepared for him by a culture puzzling over possible futures for the visual arts after the breakdown of the standard Modernist narratives. The New York and international art worlds wanted not merely novelty, but a notional authenticity, and a young, ostensibly African-American artist, with street cred, a raw gift and restless allusiveness seemed to fit the bill. In fact, Basquiat is better described by Robert Farris Thompson’s term “African-Atlantic”: although he grew up mainly in New York, his father was Haitian, his mother Puerto Rican.

The art world wanted not merely novelty, but a notional authenticity—and a young, ostensibly African-American artist, with street cred, a raw gift and restless allusiveness seemed to fit the bill

Pop art had brought energies, materials and content bubbling up from the seabed of American mass culture. The infiltration of sexual and ethnic identity politics in the 1970s and early 1980s opened new sources of reference, formal challenge and critical debate. In New York, it all happened against the background of physical and social decay and potential civic bankruptcy, with high crime but—by today’s standards—low living costs. As much a magnet as ever for ambitious creative types, Manhattan circa 1980 yet again became an incubator of wild adventure in music—punk and hip-hop—in film and the other visual arts. It was an eruption that, for a rising generation, buried the asperities of Minimalism and conceptual art.

The late Glenn O’Brien (1947-2017), a recording angel of the scene, sums up the zeitgeist retrospectively in a Barbican catalogue essay. “That was a time of geniuses together,” he writes. “We competed and it looked like collaboration... There was a viral outbreak of contagious fun and madcap genius. And here we are left shaking our heads and asking what happened to the fire and the brilliance. It didn’t last of course... There might be a thousand great musicians in this town, a thousand great artists. But in the end a dozen become stars, become legends. It’s scale effect... The market wants a few hits. Basquiat was the best of our bunch, but it was a brilliant bunch. The best of the best, he made a trillion dollars’ worth of art and they paid him peanuts. SAMO©=MC2 What a business this art is!”

The exhibition’s subtitle, Boom for Real, springs from a phrase Basquiat wrote on an apartment wall, but it chimes nicely with O’Brien’s equation for the ultimate explosion of critical and market enthusiasm for his work.

Basquiat came to public attention gradually through his tagger signature: SAMO©, meant to be read as “same ol’, same ol’ [shit]”. As a street artist, initially with his partner Al Diaz, Basquiat scrawled on the walls of not-yet-gentrified Lower Manhattan messages such as “SAMO© as an alternative 2 ‘playing art’ with the ‘radical? Chic’ section Daddy$ funds 4U...”, just puzzling enough to set those who saw them wondering who he might be and what he might be up to. (His friend Keith Haring did the same with unsigned, wordless chalk drawings on the black paper postings in subway stations that blotted out expired advertisements.)

Among graffiti practitioners, Basquiat was a “writer”, in the sense that taggers intend, more than an image maker, a fact reflected in the raggedy line jumping between drawing and inscription that electrifies his most arresting works on paper, canvas or board. He had drawn unstoppably from an early age. His habit of marking every vacant surface sometimes caused him housing troubles before the mainstream art business discovered him.

Jean-Michel Basquiat's Untitled (Pablo Picasso) (1984) is on show in Basquiat: Boom For Real at Barbican Art Gallery, London Tristan Fewings / Getty Images. Private collection, Italy; © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York

The Barbican survey confirmed Basquiat’s native gift. He had clearly looked hard and admiringly, eyes-on and in reproduction, at the work of Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg, Francis Bacon, Clyfford Still and Robert Motherwell, at Jean Dubuffet, Picasso, Leonardo and tribal arts, and let them all inform his sensibility. A copy of Gray’s Anatomy given to him by his mother while he recovered from a childhood car crash injury never ceased to fascinate him.

But as important as his art influences, maybe more so, was his desire to celebrate—by naming, listing or patchy image allusions—heroes of African-American culture, especially athletes and jazz musicians. Raised during the gaining years of the civil rights movement, he experienced racism differently from his elders, but its effects were among the currents that energised his work.

The enduring vividness of his art springs from its air of openness in all directions, of a sensibility compulsively scanning and scavenging the cultural landscape in search of its own interests, attuned equally to the sound and look of words and phrases, if indifferent to spelling. Paintings such as A Panel of Experts (1982) and Five Fish Species (1983) and dizzying works on paper such as Untitled (Alice in Wonderland) (1983) and Untitled (Estrella) (1985) encourage us to regard Basquiat as a collage artist, devoted to collisions in picture content, cultural source material and his own emotional experience.

As forcefully as some of Basquiat’s works still meet the eye, in Basquiat: Boom for Real, they have a fossilised quality, as if unable to break free of their embeddedness in a certain New York moment. Nothing defies resuscitation or export like the essence of cultural scene gone by.

• Basquiat: Boom for Real, Barbican Art Gallery, until 28 January; Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, 16 February-27 May