Never before and never again: Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (until 12 February 2018) is the cultural event of the year. The loan show is doubly overwhelming both in the quality of the works presented —133 drawings, three marble sculptures and the earliest painting by the artist, The Torment of St Anthony, made when he was just 13 years old—and its popularity. As of last weekend, attendance topped 500,000, meaning around 7,000 visitors have arrived to see it each day since the exhibition opened on 13 November, the museum recently reported.

Early in the show's run, visitors hoping to beat the crowds lined up outside the Met an hour before it opened at 10am, and for 10 or 15 minutes, they could enjoy the show in relative comfort. On recent visits, however, no matter what time you go there are viewers two and three people deep craning their necks to get a peek of the masterpiece is in front of them. In times like this, one is grateful to have curator friends who can slip you in at 9am. There is only one morning of early viewing for members remaining on 27 January before the show closes, but hopefully for the final weekend (9-11 February) there will be special late-night hours, as there were for the Met’s similarly popular China: Through the Looking Glass exhibition in 2015.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Female Figure Seen in Bust-Length from the Front (Cleopatra) (1530-33) Casa Buonarroti, Florence

Organised by Carmen C. Bambach, a curator in the museum's department of prints and drawings, the exhibition is divided into eight sections, from the artist's beginnings in the Ghirlandajo workshop through his multiple careers as painter, sculptor, architect, designer and teacher, with byways into the works of his most important associates, such as Sebastiano del Piombo, Daniele da Volterra and Marcello Venusti. An entire room—the exhibition’s most densely crowded—is devoted to drawings for the Sistine Chapel. (The blown-up photo of the famous ceiling, which hangs above, is the one complaint I’ve heard about the show from “tasteful friends”).

Bambach’s catalogue is an essential accompaniment to the exhibition, offering a remarkably gripping account of the artist’s career, his fractious relationships with patient patrons, his deft manoeuvring between leading political factions in Florence and Rome and his jealousy and rivalry with Leonardo and Raphael. The exhibition debunks the established view of the irritable, melancholic artist as a solitary genius, demonstrating his generosity to his fellow artists and assistants, and clarifying previously shadowy figures like his wily pupil Antonio Mini.

Michelangelo’s capacity for deep friendships resulted in the shows’ most personal and most affecting drawings, the famous highly finished allegorical and mythological sheets in black and red chalk given to the young noblemen the artist had fallen in love with, Andrea Quaratesi (the subject of Michelangelo’s only known portrait drawing, now in the British Museum) and Tommaso de’ Cavalieri. Michelangelo’s equally devoted and chaste relationship with the poetess Vittoria Colonna inspired his most moving religious drawings, notably the relatively little-known black-chalk Lamentation in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston and a series of startlingly intense black studies of the Crucifixion.

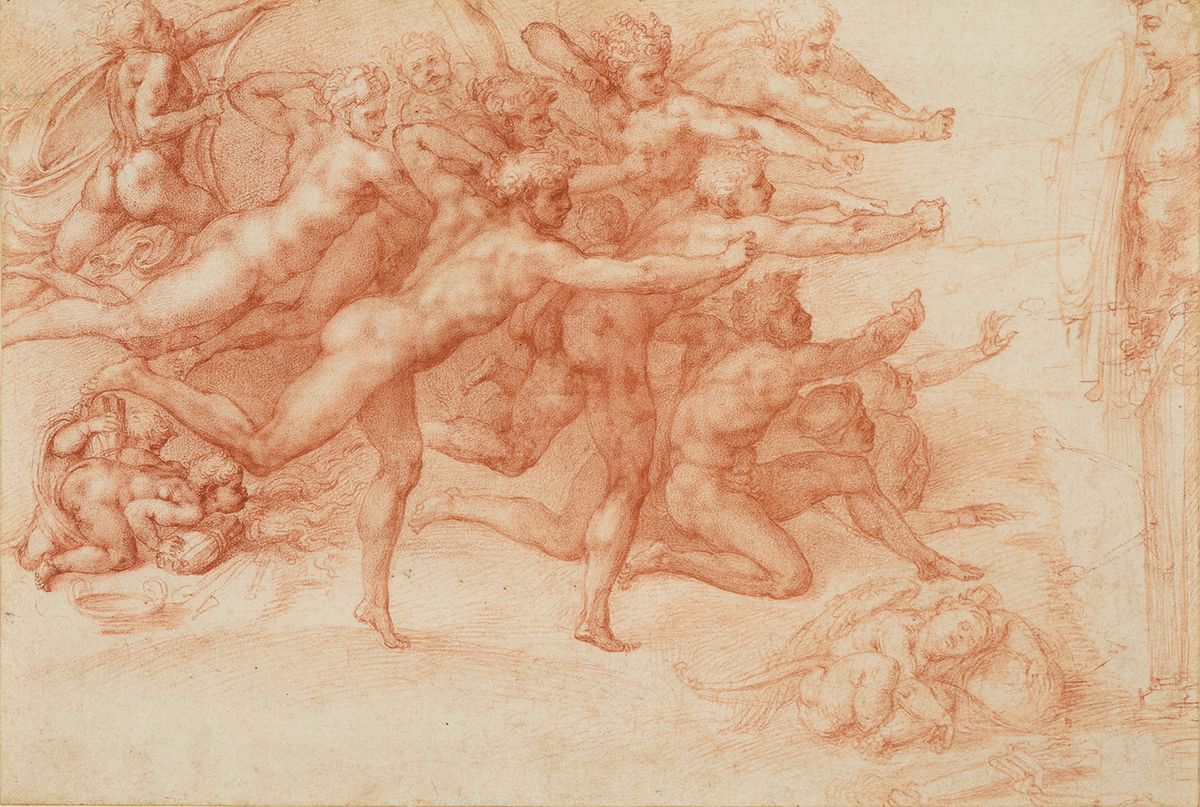

Michelangelo Buonarroti, Cartoon with a Group of Soldiers for the Crucifixion of Saint Peter Drawing (1542-46) Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples

Michelangelo’s work as an architect is also amply represented, not just through the detailed wooden model he built for a chapel vault, but in his drawn studies for the Laurentian Library, the Facade of San Lorenzo, the tombs of Pope Julius II and Lorenzo and Guiliano de’Medici and the Fortification of Florence, which are among the most studied and surreptitiously sketched by visitors in the exhibition.

For those who are unsure if they should brave the queue, I have some advice: have patience, take your turn and refrain from muttering whispered insults at the selfie-snappers who stop the flow, because the works are worth the wait.

• Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fifth Avenue, until 12 February 2018