On 8 December, an international declaration on the digital recording, documenting and, in some cases, re-creation of works of art was launched at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A). Its name is ReACH (Reproduction of Art and Cultural Heritage) and the signatories are the V&A, Unesco, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, the Warburg Institute in London, the Palace Museum in Beijing, the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage at Yale University, and Factum Arte in Madrid. Others are expected to follow. The backer of ReACH is the Peri Foundation.

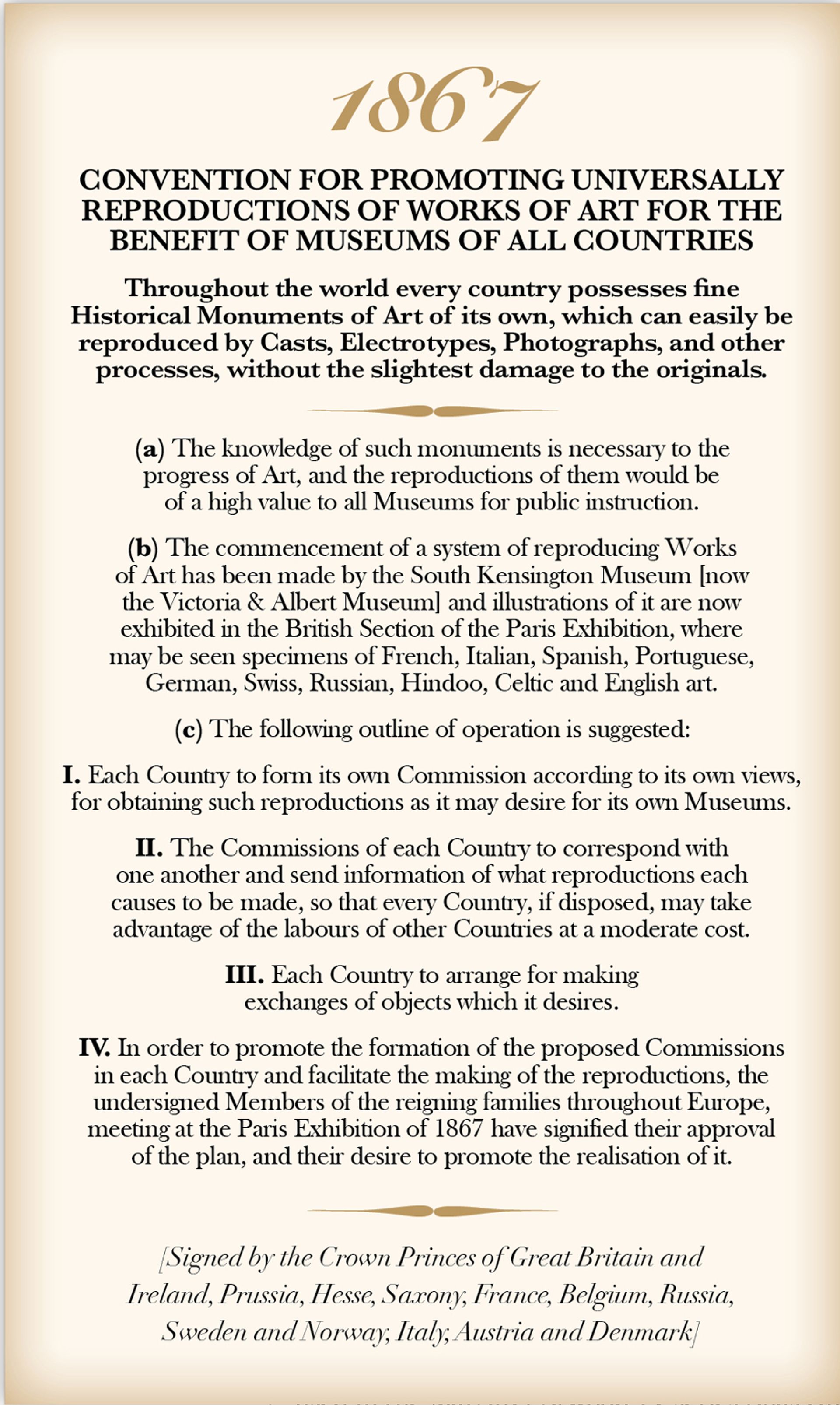

The project has evolved out of the V&A exhibition at the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, when the iconoclastic fury of Islamic State was at its height. Called A World of Fragile Parts, this looked at how copies could help preserve heritage at risk not just from war but climate change, tourism and simply the passage of time. The declaration is also in response to the vast possibilities offered by digital technology—ultra hi-res imagery, 3D printing, virtual reality (VR)—something in which Google Arts & Culture has given museums a crash course. It commemorates and revives the spirit of the almost forgotten but groundbreaking 1867 convention for the reproduction and sharing of works of art by means of plaster casts, photography and electrotyping, initiated by the first director of the V&A, Henry Cole (see illustration).

This plaster cast (around 1889) of an unknown woman by the Renaissance master Francesco Laurana (1472) is a record of the original in the Berlin Museum, damaged during the Second World War Shakko

As with the Gettysburg Address, Cole packed a lot into very few words; today’s declaration needs four sides of A4, but then the signatories are not princes who can simply command. ReACH’s first aim is to record works for the sake of documentation, especially where they are at risk, noting what has been recorded and why. Tristram Hunt, the director of the V&A, says: “We want a global conversation, not just about first-world problems of digital reproductions, but heritage considerations in difficult circumstances.”

The second aim is to encourage institutions and individuals that have created digital material to share it between themselves, but also make it freely available to the public “for personal use and enjoyment and for non-commercial research, educational, scientific and scholarly use”.

Digital obsolescence is a growing problem and ReACH commits itself to producing a set of standards that will be revised as technology evolves. It says that the parties making the records need to work collaboratively “to develop compatible systems to enable the exchange of recorded data and metadata on a global scale”.

The ReACH team has consulted widely with experts and has held five workshops around the world at which much practical detail has been considered, such as what platforms to use for sharing the assets (Google, Wikimedia or others). On the legal front, it has gone into such matters as reproduction rights, acknowledgement or compensation of the author, how to prevent “copyfraud”, and licensing issues; on the ethical front, how reproductions should be produced so that they cannot be confused with the original. It has gone to great pains, however, to make the declaration as generous and open-ended as its 19th-century predecessor.

At the conference to mark the launch of the declaration last month, the emphasis was on the people-power of the digital image. One speaker quoted the theorist of architecture David Gissen, who has said that 95% of our first encounters with a work of art are through a digital reproduction. This means that it would be self-harming for cultural institutions not to make their works easily available by this medium. The message was, instead of trying to restrict and hold on to images, make use of their popularity: Merete Sanderhoff from the Statens Museum for Kunst (SMK), Copenhagen, described how they reacted when they saw their pictures used in the Margaret Atwood TV series Alias Grace. They did not make a fuss and insist on being in the credits, but added details of the pictures to the Wikipedia entry about the series and got much wider exposure. SMK also supply digital “toolboxes” with their images so that people can manipulate them and turn them into new works of art.

The intention behind ReACH was summed up by Stefan Simon, the director of Global Cultural Heritage Initiatives at the Yale Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage, when he said: “This project is not so much a protocol as a process that will open up to the world.”