Most art historians are well aware of Stendahl’s Syndrome. My dictionary defines it as “a psychosomatic disorder that causes rapid heartbeat, dizziness, fainting, confusion and even hallucinations when an individual is exposed to art over an inordinately long period of time”. With the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s fat new $25 admission charge, we can expect an epidemic.

Many visitors from, say, North Haven, Connecticut, where I grew up, go to the Met a couple of times a year. I can imagine them today, having paid $25 a pop, wandering through the galleries, raving and falling over, exhausting their endurance to get their money’s worth. A couple of hours is all most of us can take while staying sensate.

The hefty new charge, imposed on all visitors except New Yorkers, seems a lazy and greedy approach to the Met’s money problems. It puts me in a questioning frame of mind.

A portion of the Met’s $3bn endowment is restricted but, realistically, the only money the Met can’t use for operating expenses is acquisition funds. Its budget woes didn’t happen at once. Where were the trustees? Was there not a Scrooge or two among the power elite at budget time?

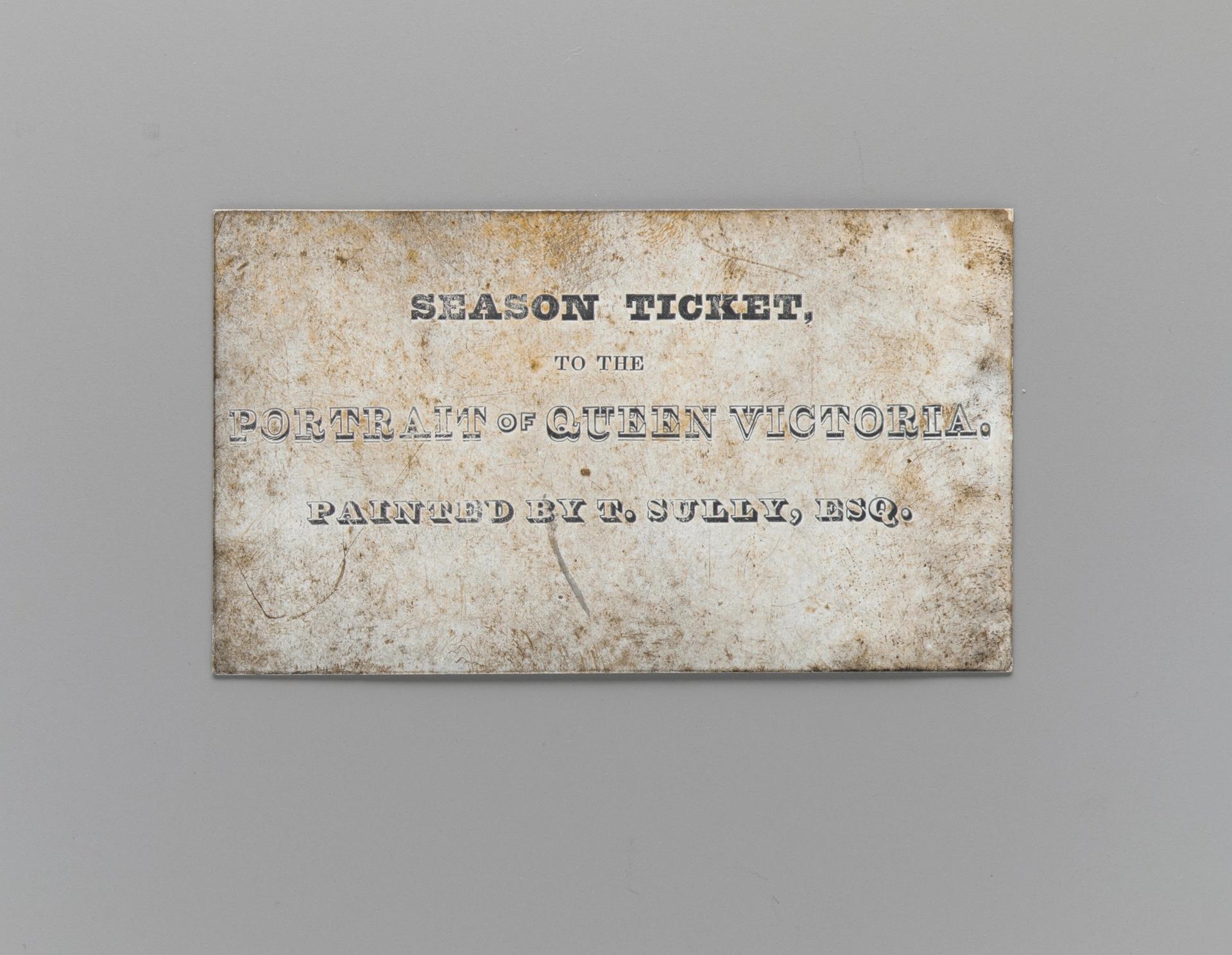

Season Ticket to the Portrait of Queen Victoria by T. Sully, Esq (1838 ) Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

What about expenses? The Met has three big problems with its budget. First, over the years, like many big not-for-profits, its back-of-house personnel costs—that is to say, its ratio of curators to non-curators—has shifted towards fundraisers, press agents, marketeers, technocrats, HR compliance bureaucrats, and even a few lobbyists. The right ratio should be overwhelmingly in the curators’ favour.

Second, the multi-million-dollar cost of the new logo no one likes is not unique. We just don’t see such blunders every time they happen. Third, the Met does 45 shows a year now instead of 60. A more digestible number is probably half of 45. Assuming the Met has three cycles a year, like most museums, that is still seven or eight per season. This would vastly simplify its marketing operations, too.

How many times have I wandered alone in galleries filled with splendid El Grecos, Goyas and Homers? Hundreds. Even the tiny, $50m Duccio lives unadored much of the time. One obvious idea is a charge for special exhibitions only, keeping the permanent collection free.

Serious attention to these areas alone would negate the need for a $25 admission charge, which incidentally is more than three times America’s minimum hourly wage. Given that the trustees didn’t put the brakes on the spending spree long ago, isn’t a penitential boost in their annual giving appropriate?

Instead, the Met punishes tourists, and this includes hundreds of thousands of Americans who already subsidise it. I suspect it has saved millions of dollars in insurance costs over the years through the federal indemnity programme run by the National Endowment for the Arts. The Met is probably the scheme’s biggest user. Then there is the federal immunity from seizure law. Museums don’t do shows that rely on foreign loans without it.

The museum’s president Dan Weiss correctly notes that almost all the Met’s money and art comes from philanthropy. But it is not just New York’s wealthy patrons that have given to the museum. Since the advent of the federal income tax more than 100 years ago, almost all of the Met’s philanthropy has been tax deductible. The Met’s endowment draw is tax-free. It pays no capital gains taxes. These exemptions have cost billions of dollars. The Met is arguably America’s biggest tax-subsidy museum beneficiary. Those assumed freeloaders from, for instance, Iowa have correspondingly paid higher taxes.

American museums are striving to achieve greater accessibility. The best path to access is free admission. This is simple economics and irrefutable logic. The family from little, middle-class North Haven—which at 80 miles puts them far closer to the Met far than Buffalo—doesn’t have the incentive to buy a membership if it only visits a couple of times a year. It is more likely to feel priced out of Met visits. And if it can’t consider keeping access free, the Met might have to pay out for banks of fainting couches to accommodate the wave of Stendahl’s Syndrome it will unnecessarily produce.