Shortly before Christie’s sale of post-war and contemporary art in New York on 15 November 2017, the auction house learnt of a potential new bidder: a little-known Saudi prince, Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud. According to the New York Times, a scramble ensued to establish his identity and financial means, and, in order to bid, he had to pay a $100m deposit for a red paddle.

The work he bid for, Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi (around 1500), went on to make a record-shattering $450.3m and was bought by Abu Dhabi with the prince acting as a middleman, but why did all the bidders on the high-value work need a special paddle? Quite simply because Christie’s wanted to be sure the final buyer would pay up.

Such high-profile prices rightly make auction houses wary when it comes to payment. One of the first public cases was of Van Gogh’s Irises sold at Sotheby’s New York in 1987 for $53.9m—the highest price ever paid at auction for a painting at the time—to the Australian businessman Alan Bond. But he could not pay, and Sotheby’s had to lend him around half the purchase price, later brokering its sale to the Getty Museum.

Then there was the Chinese Qianlong vase, hammered down at £43m at the small UK auction house Bainbridges in 2010. The buyer never paid. Only in 2013 was the vase actually sold, in a deal brokered by Bonhams, reportedly for between £20m and £25m, according to Bloomberg News.

François Curiel, Christie’s chairman for Europe and Asia, says the number of defaulting buyers in its business is “fairly negligible”. Nevertheless, for high-value lots the firm makes special arrangements—which may include asking for a deposit, as in the case of Prince Bader.

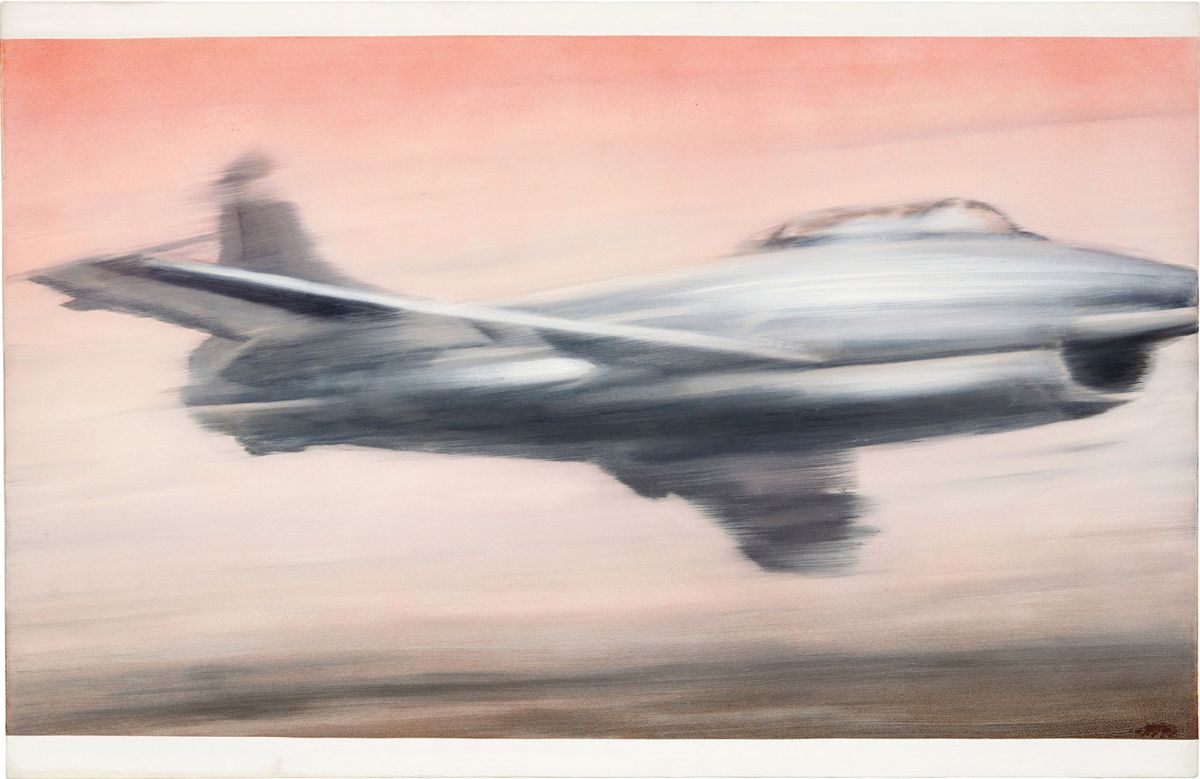

Despite this, cases of non-payment seem to be on the rise. A complex lawsuit currently in a Manhattan courtroom concerns a $24m Richter painting which a Chinese bidder, Zhang Chang, agreed to buy in November 2016 at Phillips New York through an irrevocable bid. However, he did not pay up, and Phillips has taken him to court.

Such cases rarely reach the courtroom. Dealers and auction houses are reluctant to broadcast instances of non-payment, for fear of encouraging the practice—and they are even more disinclined to sue. And yet, according to the Paris lawyer Antoine Trillat: “We see these things all the time at a lower price level than the multimillions. Buyers change their minds, then they say, for instance, that they didn’t realise that shipping or taxes would be so high.” Trillat says that in most cases it is not worth taking legal action—the costs are just too great.

The Pink Star diamond Courtesy of Sotheby's

The Pink Star

One high-value default was recently revealed in Sotheby’s regulatory filings: the Pink Star, a 59.6-carat pink diamond bought by the New York diamond cutter Isaac Wolf for CHF76.3m (around $83m at the time) in 2013, had never been paid for. Wolf was apparently bidding on behalf of a consortium headed up by a Russian who subsequently backed out. As the sale of the stone was guaranteed for $60m, Sotheby’s paid the vendor and took the Pink Star back into its inventory, valuing it at $68.4m and selling off a half share to an unidentified “partner”. The saga came to a happier conclusion in 2017 when the gem was reoffered at auction in Hong Kong and sold for HK$553m (around US$71m).

Andrea Danese, the chief executive of Athena Art Finance, which provides art-backed loans, says he saw a distinct change in approach in 2017. “Cases like the Richter are the tip of the iceberg,” he says. “We are seeing a trend, notably with Chinese buyers. Exchange controls have been tightened up in the country, and some are unable to complete their purchases in a timely manner.” Danese says his firm has been asked to provide cash advances to the auction houses and dealers to help transactions complete.

Indeed, in the Art Basel/UBS Art Market 2017 report, the author Clare McAndrew noted that non-payment was increasing in China. “In the period from May 2015 to May 2016, the non-payment rate at Chinese auctions rose to 41%, up 5% year-on-year and from a low of 30% in 2013/14,” McAndrew wrote. A historic cultural difference might play a part here. “In China, bidding is not always perceived as a legal obligation,” according to one observer, and the fall of a gavel can be seen as the start of a negotiating process, not the end. It is a misunderstanding that has caught out auction houses in the West and in China.

Trail of unpaid purchases

Chinese buyers are not the only defaulters. Saud Al Thani, the Qatari sheikh who died in 2014 and was once the biggest art buyer in the world, was notorious for leaving a trail of unpaid purchases. In 2012 a lawsuit revealed he owed $26m to Sotheby’s, £4.3m to Bonhams and £12.2m to three coin dealers. The dealers took him to court, but the case was settled. More recently, the Dubai-based Iranian collector Farhad Farjam was the subject of a lawsuit brought by Bonhams for more than £1.2m in unpaid purchases, a sum Farjam disputed. The issue was settled confidentially last year.

Chronic non-payment might be what makes headlines and court cases, but, according to one London-based dealer, absolute refusal to pay for works is less of an issue than excruciatingly slow settlement. “Sometimes it can take years; you have to go on and on asking,” he says. “But you don’t want to alienate clients.”

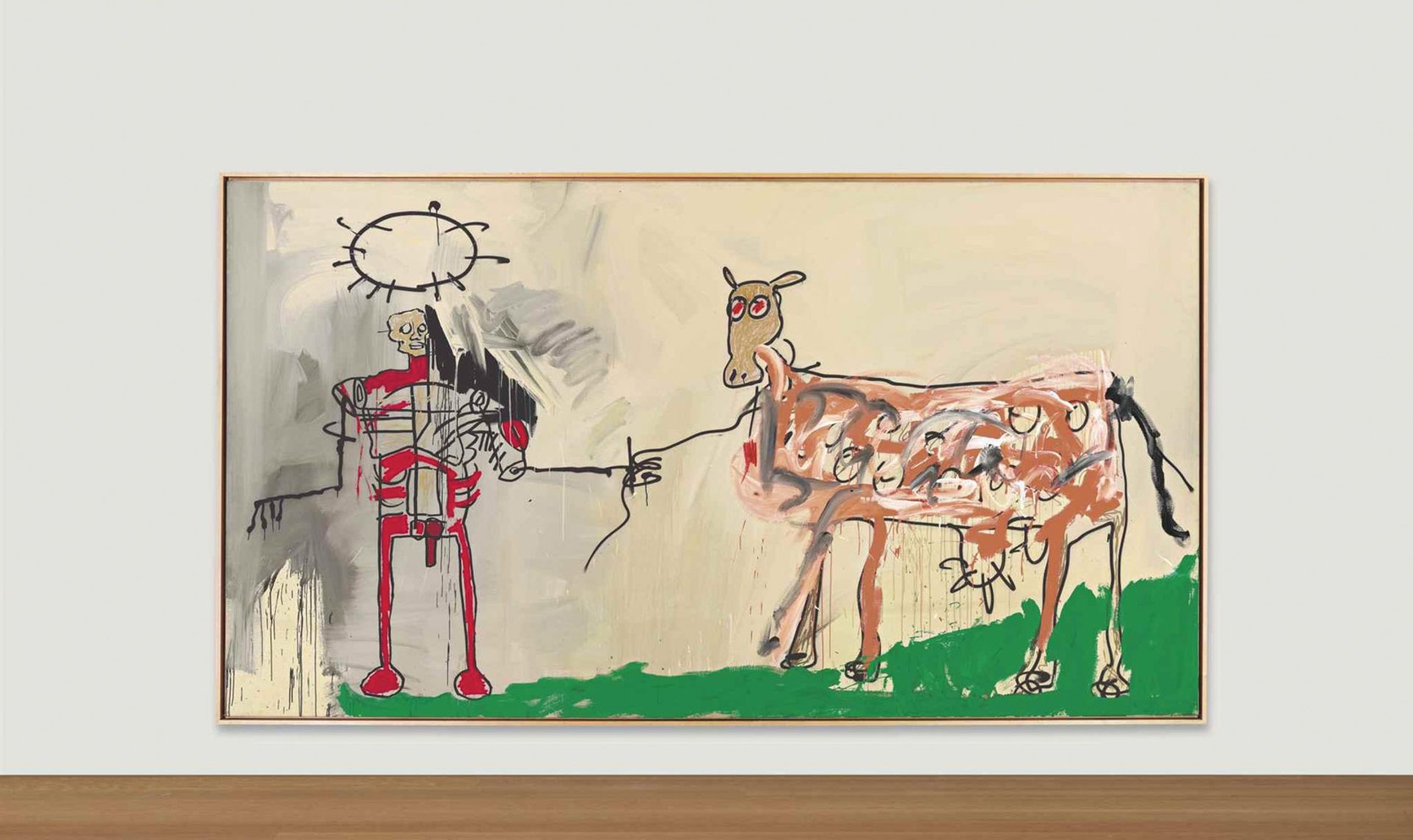

Christie’s sued over non-payment for Jean- Michel Basquiat’s The Field Next to the Other Road Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat

The art trade remains an often personal business, where relationships are important. Nevertheless, in 2016, Christie’s sued Jose Mugrabi for not respecting the payment terms for Jean-Michel Basquiat’s The Field Next to the Other Road (1981), which he bought in New York in May 2015 for $32.1m.

The Mugrabi clan of dealers are a major force in the saleroom as vendors and as buyers, but court documents reveal that the Basquiat transaction was not an isolated incident: “We, thus, yet again face the situation where your current debt position at Christie’s has raised concerns that will likely restrict Christie’s from being able to enter into transactions with you,” declared an exasperated letter from the firm included among court documents. The lawsuit was subsequently settled confidentially. Jose Mugrabi told The Art Newspaper that he, his family and Christie’s were pleased to have resolved the dispute and looked forward to continuing their “long and fruitful relationship”.

As for Phillips, the complex saga involves a second Chinese collector, Lin San. As well as taking Zhang to court, Phillips is attempting to claim Francis Bacon’s Study for Head of Isabel Rawsthorne and George Dyer (1967), which was bought by Zhang at Christie's on 30 June 2015 for £12.1m. Lin says that he lent Zhang the money for his art purchases–and that Zhang had given him the Bacon instead of repaying the loan.

The various parties are thought to be moving towards a settlement – although the outcome of which will likely remain confidential.