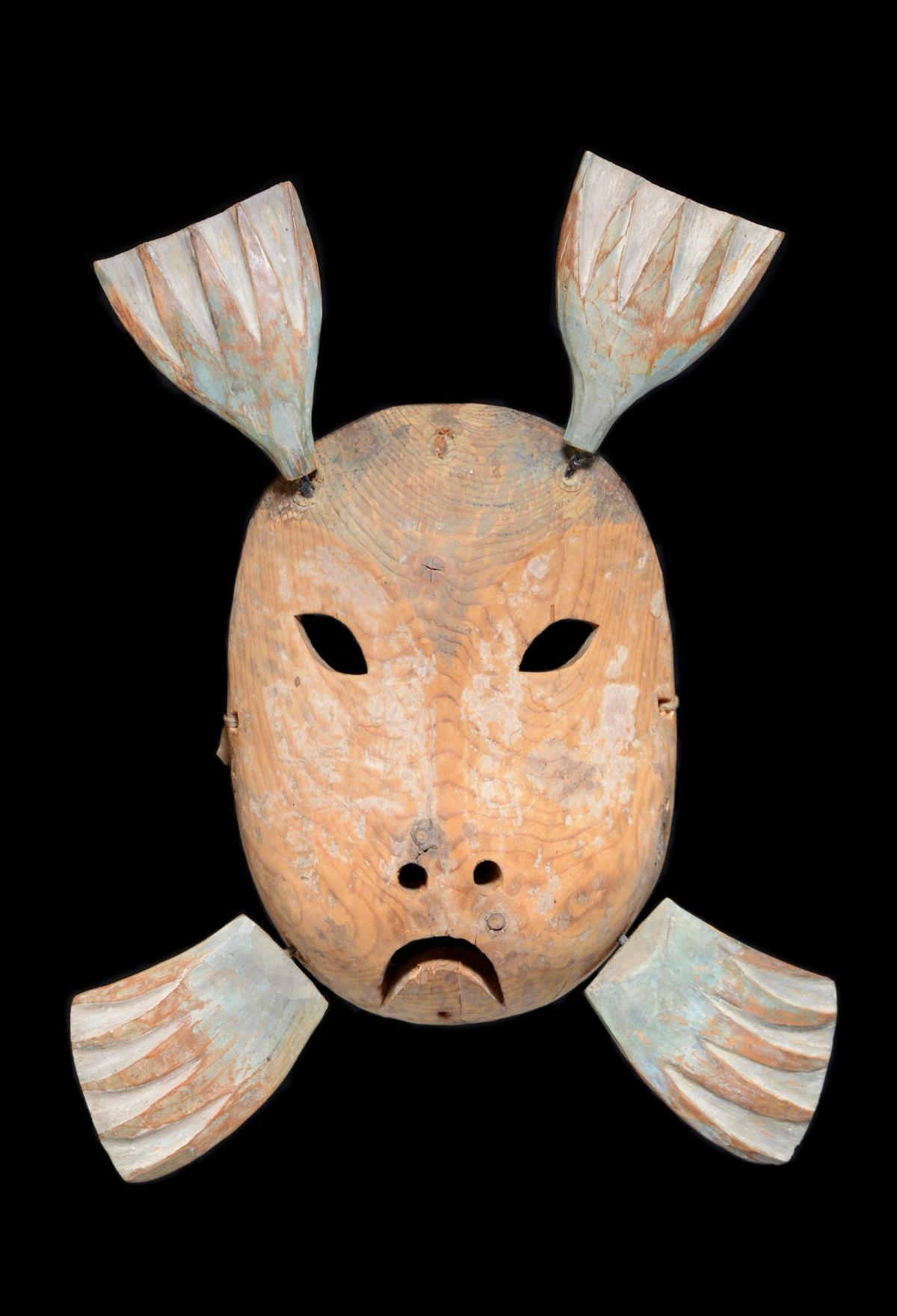

Yup’ik seal mask, Alaska (around 1870s)

Tambaran, New York

$100,000

This late 19th century mask, made of painted cedar wood, was created by the Yup’ik people of southwestern Alaska and represents a seal’s face and four flippers. Yup’ik shamans instructed carvers on how to fashion such animal masks, which were worn in dance ceremonies prior to seasonal hunts. Seals are especially revered in Yup’ik culture, and this ritual mask was intended as a devotional object to seals, in thanks for their vital role in Alaskan villages. As well as serving as a source of meat, seal intestines are repurposed as waterproof garments, stomachs are used as containers and skins are made into rope, clothing and other materials. Because such masks were traditionally destroyed after ceremonies, few examples remain in private hands. A smaller 20th century “seal mask”, offered in poorer condition, made around $4,000 when it surfaced at auction in 2016. More complex variations of Yup’ik masks, depicting other animals as well as medicine men, can be found in major collections of ethnographic works of art, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the British Museum, London.

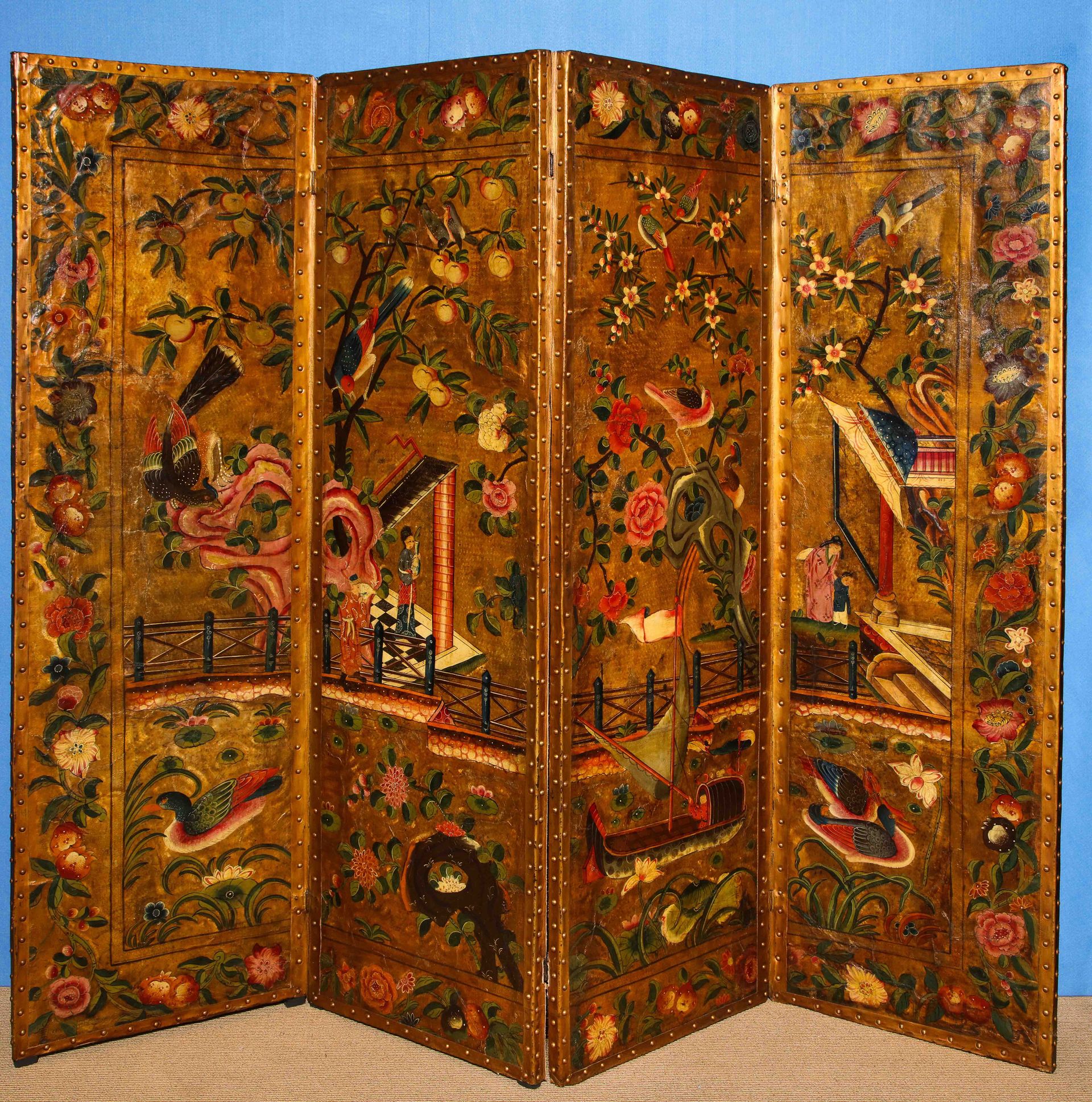

Polychrome four panel gilt leather screen Philip Colleck, New York

Four panel gilt leather screen (around 1750)

Philip Colleck, New York

$48,000

This mid-18th century English folding screen is decorated with oil paintings on leather of Chinoiserie motifs. The earliest surviving folding screens are Chinese, with some dating to the 8th century AD, and both Chinese and Japanese imports were popular in the European market in the 17th and 18th centuries. Around this time, Western adaptions also emerged, and, Mark Jacoby of the gallery says, “the English had a good reputation for producing the finest leather painted screens, and exported them throughout Europe”. Such screens also became popular in the French market; in 1899, Odilon Redon was commissioned to create a series of 17 decorative panels for the Château de Domecy-sur-le-Vault—two are now in the collections of the Musée d'Orsay, Paris and the Getty Museum, Los Angeles. As with this screen, images were typically rendered in a vertical pattern. This panel retains its original tooled gilt leather background and paint. Similar examples can be found in the collections of the British Museum, London and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Jizō Bosatsu bronze Michael Goedhuis, New York and London

Jizō Bosatsu bronze (around 1392-1572)

Michael Goedhuis, New York and London

$220,000

This Japanese bronze, dating from the Muromachi period, depicts the Buddhist deity Jizō Bosatsu, one of the four principal bodhisattvas of Mahayana Buddhism, known as the guardian of travellers and the weak. The figure is the only Buddhist deity to be shown as “both bodhisattva and a monk, being therefore both human and divine—the intermediary between men and the Buddha”, Goedhuis says. He is shown sitting down and without a staff—unusual for such sculptures of Jizō Bosatsu, who is more commonly shown standing upright and holding a monk’s staff, called a shakujō, with six suspended rings—and carries a Mani (wish-granting) jewel in his left hand. The clay core remaining in the sculpture underwent a thermoluminescence dating test at Oxford University that “reinforces our stylistic dating—it’s rare for us to be able to find a clay core on sculptures”, Goedhuis says. The image of Jizō Bosatsu, one of the most popular and widely depicted deities in Japan, was traditionally made for temples and occasionally for private residences. One similar but smaller example belongs to the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.