The problem of a painting, as Brice Marden knows, is when to call it finished. “If it ever gets done, this painting will explain to me what I’ve been doing the past decade.” He said that in 1997 of Study for the Muses (Hydra Version), a picture he had begun six years earlier. The enormous work, which is almost seven feet tall and more than 11 feet wide, was about to be included in a ten-year survey of his work at the Dallas Museum of Art, but Marden confessed it still was not quite resolved. There were just so many decisions to make: how many veins should there be and what colours were best? Where should they cross and how should they meet? How dense should the “plane image” (Marden’s favoured term) be, and which areas were best left open?

“It’s a continuous process for which there is never any full, unqualified reward,” he once said of painting. “You don’t get something done and say, ‘Oh, that's it.’ You get something done and it’s part of a living situation”, one that is always open to review.

The whole project went very fast. The whole idea of painting seemed brand new

So it was clear what Marden meant when he said at his studio in September that a painting of his, then on show at an Upper East Side gallery in Manhattan, was “unresolved”. He was right; the work seemed muddled and bare and was only nominally completed in 1987.

Yet Marden can be sceptical even of his best, most balanced and powerful pictures. He admits, as the art historian Brenda Richardson writes, “that he is not sure he would ever finish a painting if he did not have specific exhibition deadlines”. Even then, there is time for a change. The curator Gary Garrels, who organised Marden’s retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (2006-07), cautioned in the catalogue that a few of the most recent works “may return to the studio” for some alterations after the show.

Brice Marden in his studio in Tivoli, New York, in 2017. He explains that his new art is some of "the most conceptual" material he has ever produced Eric Piasecki

Shrugging off the hairshirt

Yet earlier this year, on the Hudson River in Tivoli, New York, where Marden has a home with his wife, the painter Helen Marden, he made no indication that his ten newest pictures, which had already been sent off to an exhibition at Gagosian’s Grosvenor Hill gallery in London, posed any persistent problems.

“The whole project went very fast and smoothly,” he says of the green, largely monochrome works, all done in terre verte, a pigment made from earth. “I kept thinking, ‘I’m not remembering how to paint.’ It all seemed absolutely brand new. Even the whole idea of painting did.”

“It’s interesting that Brice said that,” says the painter Chuck Close. “He has always sort of worn a hairshirt and some degree of discomfort was at least part of what he was doing.” But this time, Marden says, he felt unburdened and free, excited about an adjustment that included leaving his long-time dealer, Matthew Marks, for Gagosian. (Of that situation, he simply says he “wanted to make a change”.) The London show, his first in the city since a survey at the Serpentine Gallery (2000-01), was a chance to disavow the rumination and doubt that critics have emphasised as the keys to his achievements.

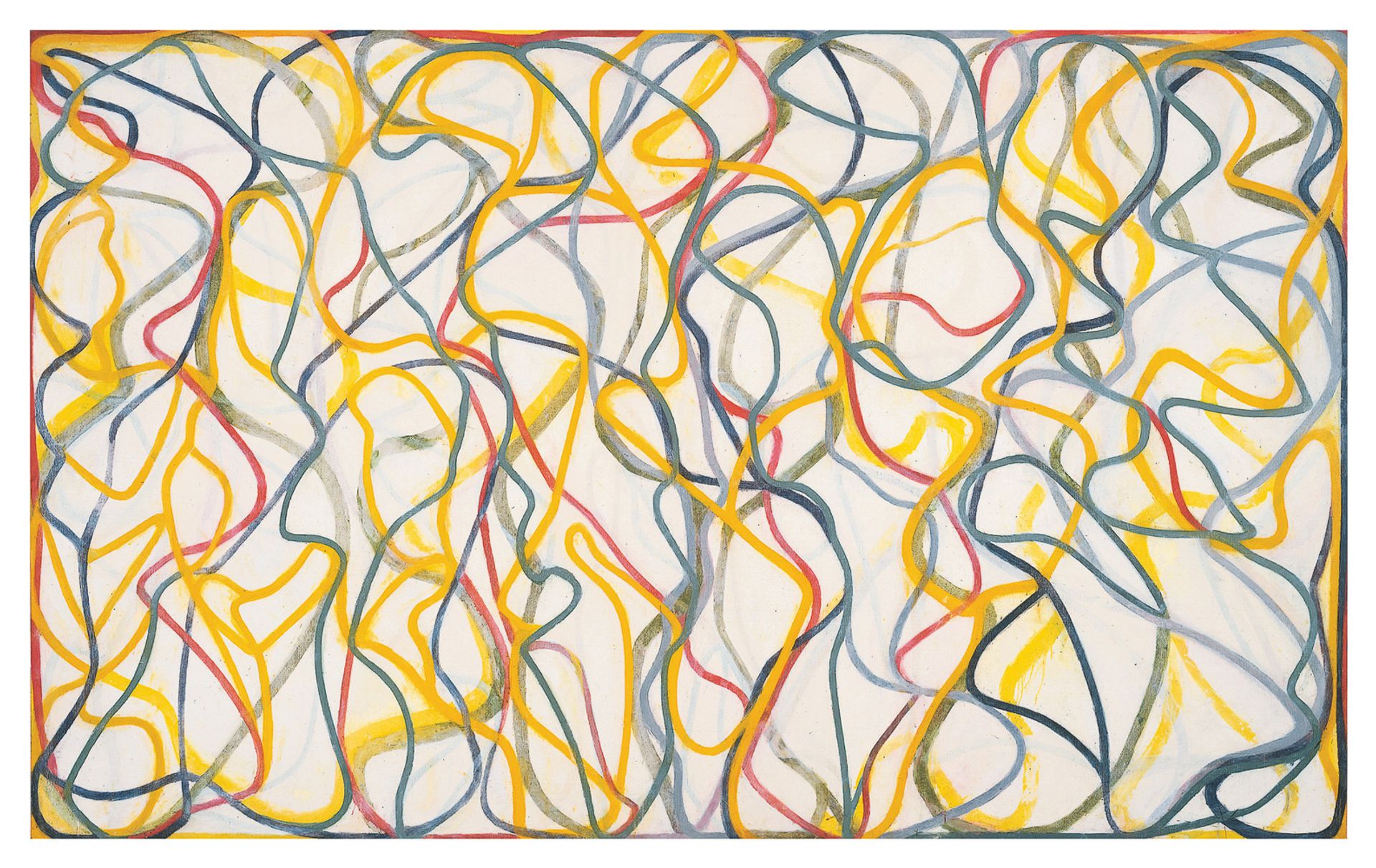

Brice Marden: Williamsburg (2016-2017) Brice Marden/Artists Rights Society, New York, 2017; courtesy of Gagosian; photo: Bill Jacobson

Marden calls his new paintings “the most conceptual group” he has ever made; once the idea was settled, all that remained was the execution. A crucial early decision was to paint each canvas using a different brand of oil paint (Williamsburg, Blockx, Holbein and so on), which mitigated overthinking. The straightforward approach freed him from other binds, too. Most importantly, it enabled Marden to relax his general proscription of perfect squares.

“The images I was making before,” he says of earlier works, “weren’t so clear, and I felt that working with a square was, somehow, kind of a cheat. You could lean on it as a sort of absolute factor”—as an easy way to unify a painting. But the simplicity of this shape was a draw in the new pictures. Although they are all made on identically sized, eight-by-six-foot rectangular supports, the painterly emphasis is on the green square that anchors the top of each picture.

Brice Marden: Blockx (2016-2017) Brice Marden/Artists Rights Society, New York, 2017; courtesy of Gagosian; photo: Bill Jacobson

Old style, new process

The simplicity of the project—ten green paintings, but none quite the same—enabled Marden to forget the complex decision-making that had been necessary for works like Study for the Muses (Hydra Version). The intricate, calligraphic style of much of the past 30 years, which is full of an infinite number of big and small variables, is replaced in the new work by a pared-down clarity that is borne of a single line of thought—which is what Marden meant when he said the process felt “absolutely brand new”.

Yet the pictures also have a clear echo of the past and inevitably recall his earliest mature works, the monochromatic paintings he made in the 1960s and 1970s. Many of those works include a narrow, relatively clear band of unpainted area along the bottom edge, which carries the residue of paint that has dripped down from above. In the new pictures, the band has been greatly expanded, but the sensibility is much the same: in each work, Marden stresses that painting is a hand-made, artificial craft and that an artist should reveal his process. This is the great through-line in every one of his paintings.

“Maybe they’re so easy for Brice to make because he’s learned so much about making them over the course of a lifetime,” the painter Pat Steir, an old friend of Marden’s, says of the new works. Indeed, it would be impossible for such an intelligent, highly educated painter (he earned an MFA from Yale University in 1963), who is so reflective of his place in the Modernist narrative, to forget everything he knew while making the green pictures.

“I have sort of gone back to doing these monochromatic paintings with the drips at bottom,” he admits. But, he adds: “Everybody thinks, ‘Oh, he’s going the old paintings.’ I don't know. I don’t feel in any way defensive about it. But I don’t feel as if I’m going back and exploring things I forgot to deal with. I’m just making paintings."

The artist’s enormous Study for the Muses (Hydra Version) (1991-95/1997) was still in progress just before it went on display in a major show of Marden’s work at the Dallas Museum of Art Brice Marden/Artists Rights Society, New York, 2017; photo: Bill Jacobson

For Marden, this is what it comes down to: whatever he may remember, whatever he may forget, painting is an imperfect process forever open to thoughtful revision. In Tivoli, as if to press the point, he pointed to a multi-panel painting of many variously coloured parts, another version of which belongs to his wife.

“There was this big debate about whether to hang it with two inches’ separation between each canvas, or to put them all together,” he says. “She liked it with the spaces in between. And I said, ‘Well, let me make another one where it’s all together.’ So I did, and that’s this one.”

But Helen, on further reflection, decided she wanted her work to be all together, too. “So I'm going to really rework this one,” he says.

• Brice Marden, Gagosian Grosvenor Hill, London, until 22 December