In January, the International Center for Photography (ICP) in New York will revisit an unsavoury chapter in American history with Then They Came For Me, an exhibition that focuses on the US government’s mass imprisonment of 120,000 Japanese Americans during the Second World War. Erin Barnett, the director of exhibitions and collections at the ICP, calls it a “powerful and timely” show that addresses “the consequences of government abuse of civil liberties under the guise of protecting other Americans”.

Organised by the Chicago-based Alphawood Foundation and Gallery—the same non-profit behind the travelling show Art Aids America, a survey of work created in response to the health crisis—Then They Came For Me functions as a cautionary tale for the Donald Trump era in the wake of the US president’s travel ban and push to deport undocumented immigrants. In Chicago, where the exhibition closed in November, the introductory wall text ominously asked: “What will YOU do when they come for your neighbor?”

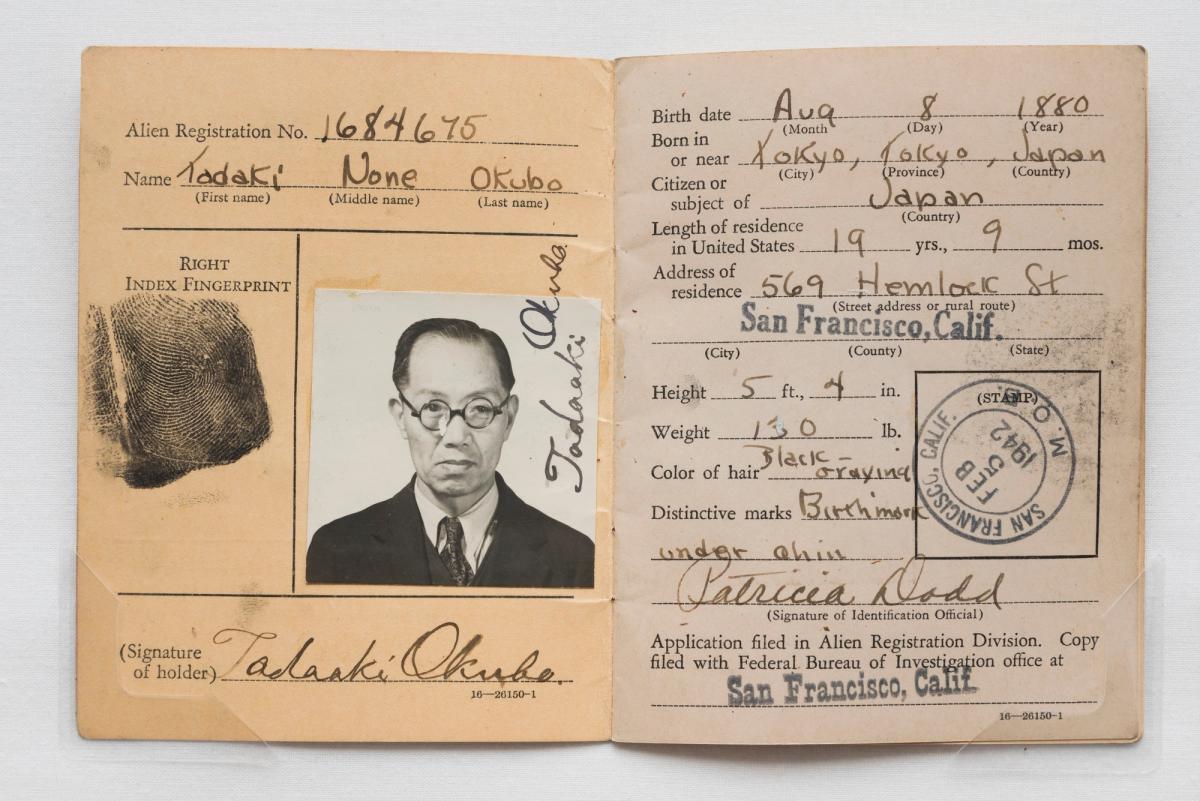

It will include around 100 images by documentary photographers like Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, and the photojournalist Clem Albers, as well as works by incarcerated artists Toyo Miyatake and Miné Okubo. Lange was an early recruit of the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the agency in charge of the displacement that sought to use photography in its propaganda efforts. Her work, however, was deeply sympathetic and opposed to the incarceration. A more direct look at daily camp life comes from Miyatake. Held at Manzanar in California from 1942 to 1945, Miyatake photographed what the government had forbidden Lange to document: the barbed wire fences and guard towers of the camps.

Barnett says that, together, these pictures “bear witness to this particularly shameful period of American history”.