The opening in November of the €1bn Louvre Abu Dhabi, dubbed the first universal museum in the Arab world, was undoubtedly the most significant museum unveiling of 2017. In an impassioned address at the event, Jean-Luc Martinez, the director of the Louvre, said: “This project is first and foremost an Emirati initiative; they have decided that the 21st century will be for knowledge and culture.” At a moment of symbolic union between Europe and the Middle East perfectly expressed in Jean Nouvel’s contemporary take on Islamic architectural traditions, Martinez spoke in the same impassioned speech about the urgent battle against fanaticism. “Our world must find antidotes to this poison of hate,” he said.

The displays, featuring more than 600 works spread across 23 permanent galleries, were also novel, bringing seemingly disparate cultures—Mayan and Nigerian objects, for instance—into new dialogues, confirming Martinez’s idea expressed to The Art Newspaper earlier in the year that European art should not be considered as a “separate entity” to that of non-Western cultures. And despite the British Museum ending its loan deal with Zayed National Museum (ZNM) in Abu Dhabi this year, Mohamed Khalifa Al Mubarak, the chairman of the Abu Dhabi Tourism and Culture Authority, told us that the ZNM and the similarly stalled Guggenheim Abu Dhabi would open within ten years.

Another museum opening outside traditional Western art centres also caught the eye. Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, in Cape Town, South Africa, housed in a spectacular conversion of a granary by the British architect Thomas Heatherwick, was billed as Africa’s first major contemporary art museum. It could not be more different to Louvre Abu Dhabi: the Zeitz is a private museum, a collaboration between the German collector Jochen Zeitz and V&A Waterfront, a developer. While the museum partly houses Zeitz’s own collection, it will also assemble its own holdings, and its governance structures closely resemble more public museums, with trustees and advisers including the artists Isaac Julien and Wangechi Mutu and RoseLee Goldberg, the founder of the Performa Biennial in New York.

The power of private museums was again reinforced in 2017, with more eye-popping initiatives at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. It followed up its exhibition of works from the Shchukin Collection (which had 1.2 million visitors) with this year’s show Being Modern: MoMA in Paris (until 5 March 2018), which features 200 works from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

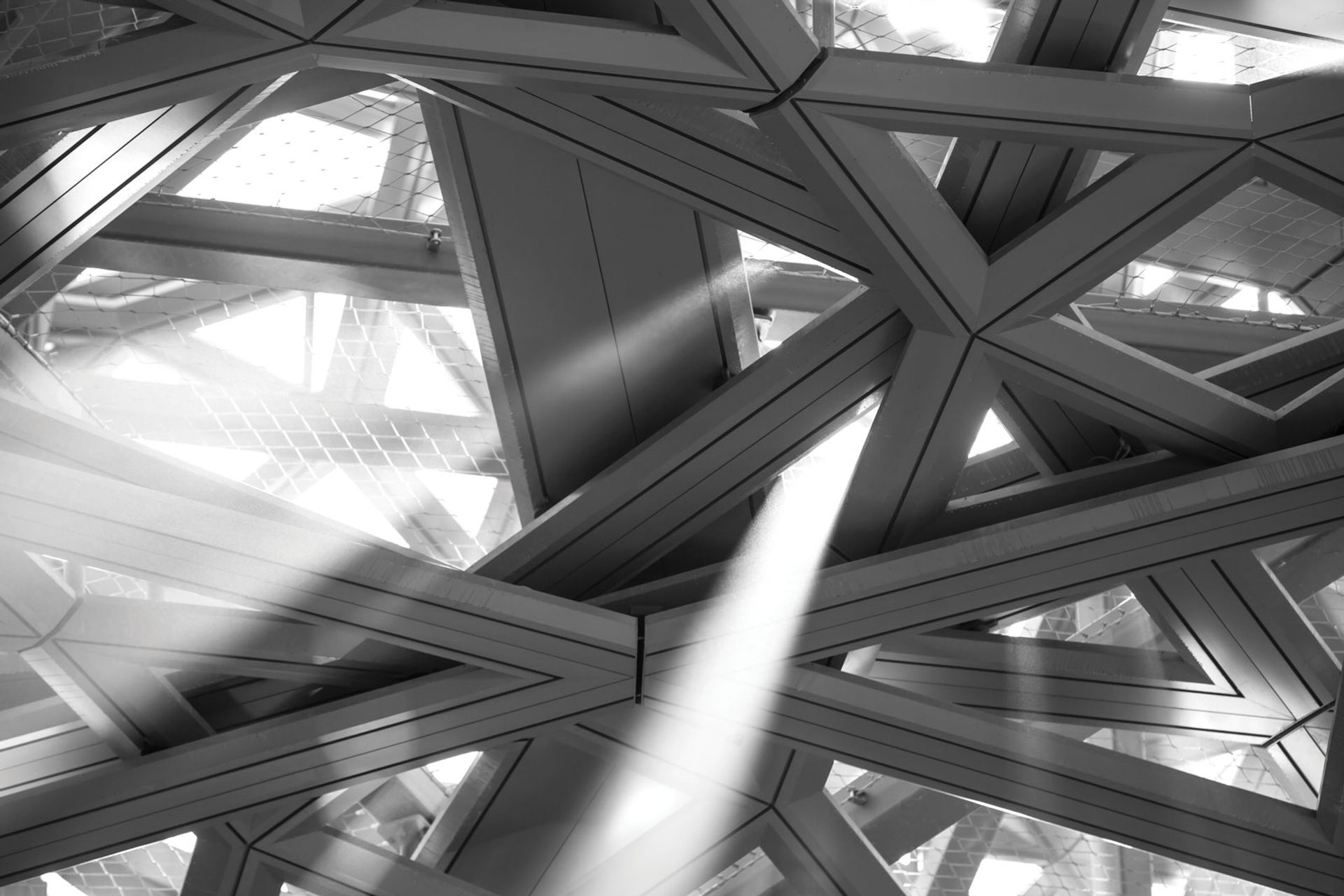

Sunlight filtered through the lattice-like roof of Louvre Abu Dhabi Abu Dhabi Tourism & Culture Authority. Photo: Fatima Al Shamsi

Meanwhile, reportedly one of the costliest exhibitions ever staged took place at François Pinault’s two Venetian venues, the Palazzo Grassi and the Punta della Dogana (until 3 December). Damien Hirst’s new body of work, 190 sculptures across 54,000 sq. ft of gallery space, featuring sculptures from a fantastical shipwreck, and called Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, cost him tens of millions of pounds. It could really only have been staged by an enormously rich artist in an enormously rich collector’s vast art space. Whether public museums would have wanted to host it is another matter; despite some surprisingly rapturous views, many dismissed the show as an overblown folly.

The most troubled museum of the year was the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. A $600m extension to its Fifth Avenue home was put on hold in January and, in February, George Goldner, who led the Met’s prints and drawings department for 21 years, spoke candidly about the museum’s problems, including its governance, treatment of staff, and the feeling among other curatorial departments “that their concerns have been relegated to a secondary position behind contemporary art and digital media”. At the end of February, Thomas Campbell, the museum’s director, resigned amid increasing scrutiny of the Met’s budget deficit and reports of tension between the administration and curatorial staff. He defended his tenure vigorously in his final press conference in May, including the emphasis on new art and digital ventures. And he mentioned the 40% increase in visitor numbers during his directorship. By September, the Met had confirmed its criteria for the next director, with no timeline set for an announcement of who it would be. Is leading this most illustrious of museums as much an ambitious curator’s dream as it used to be?