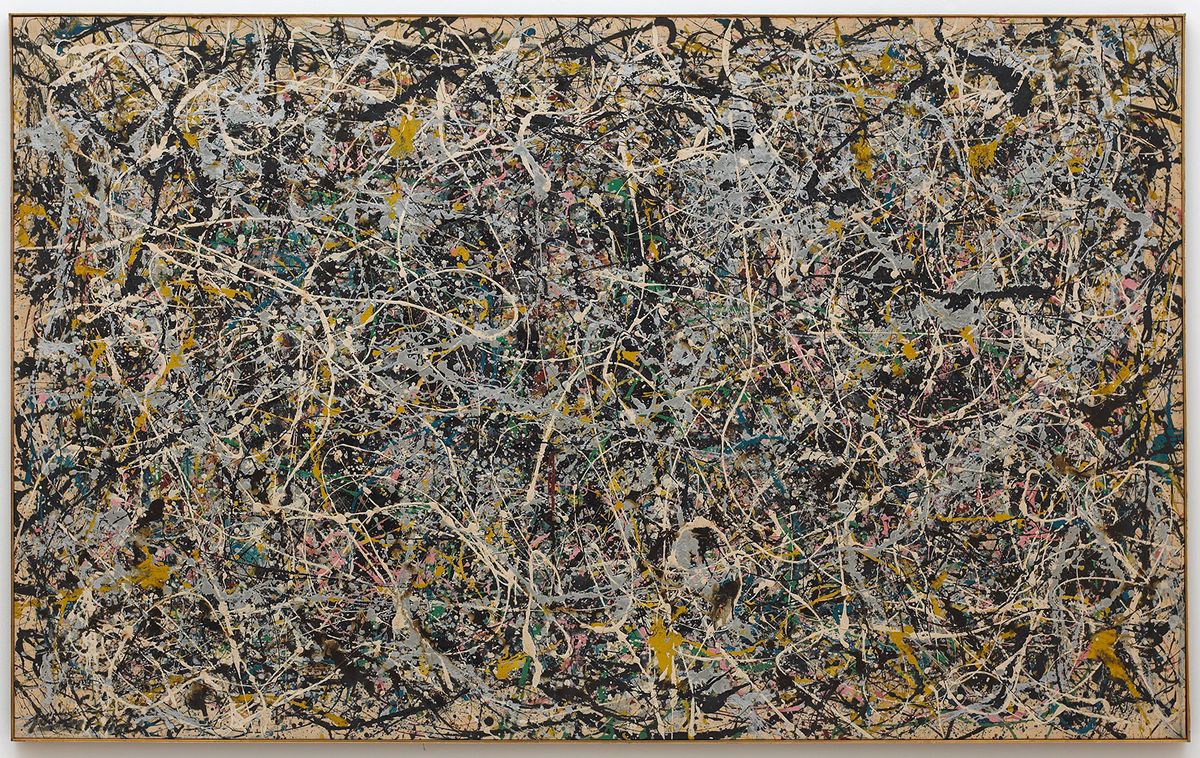

An important drip painting by Jackson Pollock, Number 1, 1949, housed in the Museum of Contemporary Art (Moca LA) in Los Angeles for nearly 30 years, is about to get a very public cleaning. The nine-foot wide canvas covered in tangles of gray, cream, gold and black paint will be restored in an open gallery at the museum’s Grand Avenue location from 4 March to 3 September, with a conservator from the Getty Conservation Institute on hand to take questions during set times (although the schedule has yet to be announced).

The GCI’s head of science, Tom Learner describes the painting’s condition as “good for its size” and gives a simple reason for the conservation treatment. “The canvas is dirty—think about all the exposure to the environment, especially on days like this, with ash falling,” he says, referring to the recent wildfires in Los Angeles. “It looks a little dull, it’s in need of a little TLC.”

The partnership with the GCI allows MOCA, which does not have its own staff conservator, “to lift the veil on this kind of work” and share the science of the restoration as it goes along, says the museum’s director Philippe Vergne.

For its part, the GCI was looking for a “test case” to try out some of the cleaning systems they have been developing specifically for Modern paintings, which often don’t respond to solvents the way more traditional oil paintings would because of the synthetic materials used. Another goal is to conduct an analysis to identify exactly what kind of paint Pollock flung or dripped in his celebrated fashion on this particular canvas. The GCI’s working assumption is that he used an “alkyd” or synthetic-resin-based house paint. MOCA’s label currently identifies it as “enamel and metallic paint on canvas”.

A very early test cleaning of one small area, done by Chris Stavroudis, a private conservator who works with the Getty who has signed on for the project, has already yielded good results. “In a lot of the off-white, almost cream-coloured enamel paint, he’s seen a significant level of dirt coming off,” Learner says.

Do they anticipate any challenges? Learner mentions some “undulations” in the canvas that need to be properly assessed and treated as well as “exposed parts of the canvas when there’s no paint at all, which are looking a bit discoloured. Sometimes those areas can be evened up, sometimes not”.

But the biggest challenge, he adds, may be making the slow science of conservation dramatic enough to hold the public’s interest. “This is an experiment for all of us,” Learner says. “Conservation is not always the most dramatic thing to watch—we have to figure out how to make it as fascinating as possible.”