"It's great to be in Miami, fishing boats in Biscayne Bay, Miami, Florida". Date issued: 1930 - 1945 Boston Public Library

Miami’s contemporary art landscape has been transformed in recent years. In 2013, the former Miami Art Museum re-opened in its new Herzog and De Meuron-designed home in Museum Park on the waterfront of Biscayne Bay, with a new name—the Pérez Art Museum Miami (Pamm), following a controversial $35m donation of cash and art from the local collector Jorge Perez. Meanwhile, the Bass Museum of Art has just reopened after a two-and-a-half year refurbishment and expansion—and has rebranded itself The Bass.

Now these established museums have been joined by the just-opened Institute of Contemporary Art Miami (ICA), while the city’s private collectors and foundations are also building new spaces or extending their exhibition space. The dramatically growing landscape of institutions, which all have to compete for audiences and funding, recently prompted the The New York Times writer Brett Sokol to question: “Can Miami afford all these art museums?” This week might offer a glimpse of the answer—and the role of Art Basel Miami Beach as an anchor for the scene—as the international art world arrives for the fair.

View of The Bass and Sylvie Fleury's Eternity Now (2015) from Collins Park Zachary Balber and courtesy of The Bass, Miami

Expanding spaces

The Bass finally re-opened at the end of October after numerous delays. The revamp means there is 50% more exhibition and public space—around 10,000 sq. ft—in the museum’s original 1930s Art Deco building and 2001 extension. A show of videos and mixed-media installations by the New York-based artist Mika Rottenberg opens this week at the refurbished venue (7 December-30 April 2018), along with exhibitions dedicated to Ugo Rondinone and Pascale Marthine Tayou.

The ICA opened on 1 December in the city’s Design District after launching in a temporary venue in December 2014. The institute has a chequered history, having been set up by the former board of trustees and staff members of the Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami who pulled out of Moca in 2014 after a legal fight with the City of North Miami over funding and administration.

A new angle: the entrance to the ICA Miami’s new venue in the city’s Design District Iwan Baan and courtesy ICA Miami

Situated on land donated by the real estate developer and Design/Miami fair co-founder Craig Robins and Miami Design District Associates, the ICA Miami has a new project space on the ground floor reserved for site-specific solo presentations. The space opened with a show of works by the Haitian-born artist Tomm El-Saieh (until 22 October 2018).

The launch programme is nothing if not eclectic with an exhibition of new, large-scale paintings by the UK artist Chris Ofili (until 27 October 2019) and a display of new grid pieces by the New Orleans-based artist Charles Gaines. New commissions by Abigail DeVille and Allora & Calzadilla will fill the ICA’s 15,000 sq. ft sculpture garden.

“I think the ICA could fill a niche by presenting really cutting-edge, experimental works of art; it could take chances with the kinds of shows it [organises] and what it wants to say, kind of like what the New Museum does in New York,” says the Miami-based art advisor Lisa Austin. “The ICA needs to appeal to a young audience, the Instagram crowd, people who may not be regular museum-goers but want to see something cool.”

But planting a flag will take time. “What distinguishes us?” asks the ICA Miami’s director Ellen Salpeter. “Our commitment and community-led ethos. All of our exhibitions and programmes are free,” she says. While many museums have education programmes, the ICA’s is notably ambitious. For example, in 2016 it launched month-long workshops for scholars and students, in collaboration with Florida International University, as part of a new Art + Research Center initiative.

Such collaborations might be the way forward for Miami’s cultural organisations. Earlier this year, Salpeter told the Miami Herald that the city’s cultural organisations must unite as arts funding comes under assault at the federal level.

Jill Deupi, the director of the Lowe Art Museum at the University of Miami, says: “Museums are, first and foremost, in the business of education… I don’t think, therefore, that we have reached a point of over-saturation since, in my estimation, the demand for accessible, informal educational opportunities for all sectors of our community continues to outstrip supply.”

Private passions

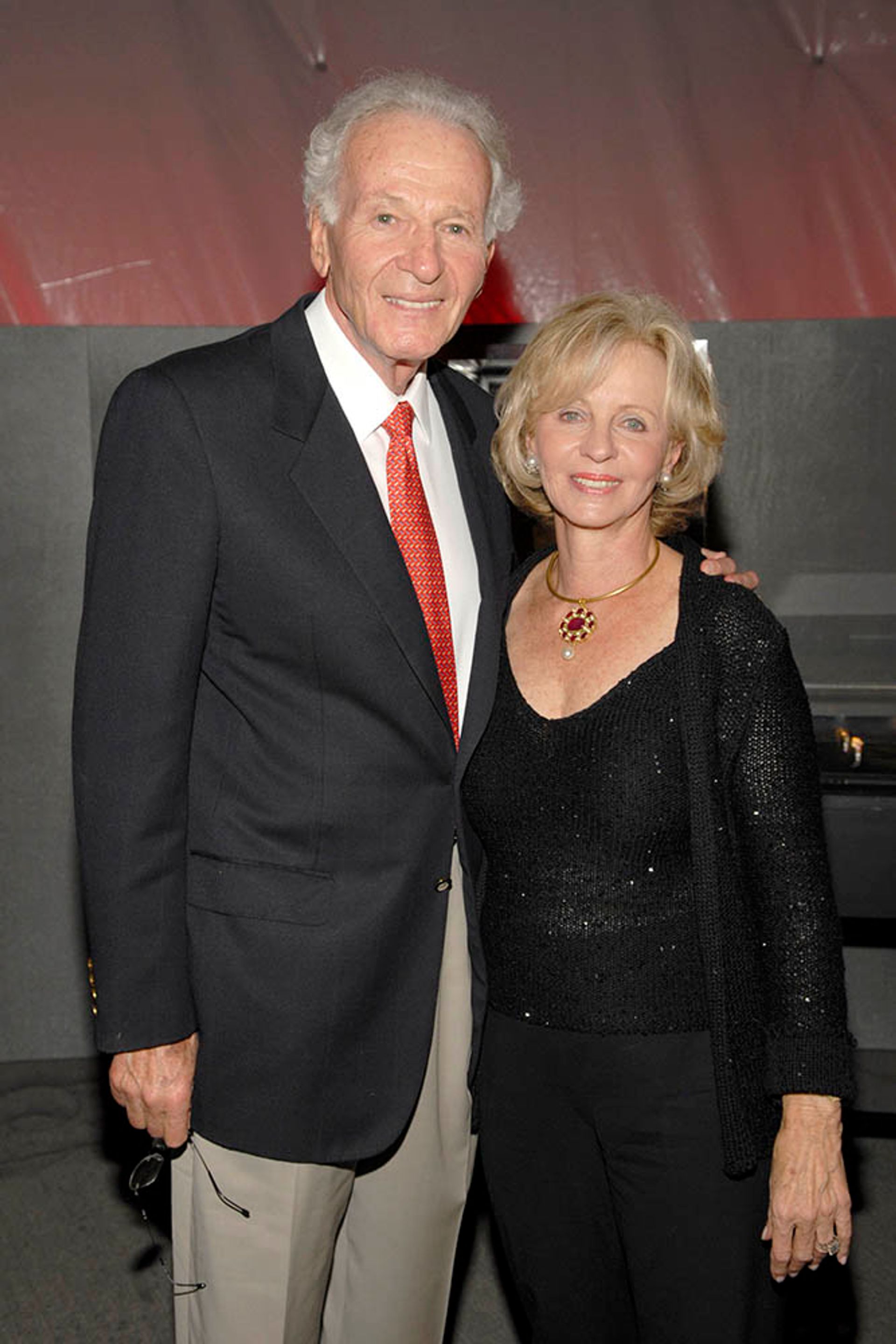

Private sponsors have paid for all of the ICA’s design and construction costs, with the local billionaires Irma and Norman Braman being the principal donors. They are among a host of wealthy individuals who are helping to reinvigorate Miami’s contemporary art scene.

Norman Braman and Irma Braman Clint Spaulding/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images

Among them is Chloe Berkowitz, a former Pamm trustee and the daughter of billionaire investor Bruce, who is overseeing a new building in the Edgewater neighbourhood to house the contemporary art collection of her family’s non-profit foundation Fairholme Unlimited (financed through donations from Bruce’s investment company). “Two monumental works from the collection—James Turrell’s Aten Reign (2013) and Richard Serra’s Passage of Time (2014)—will feature prominently within the building’s design,” a project spokeswoman says.

Meanwhile, the Rubell Family Collection, which presents thematic collections from its 7,500-strong collection, is due to leave its current location in Wynwood to move east to a new 100,000 sq. ft building in the Allapattah district. More than twice the size of its current 40,000 sq. ft facility, the new space, designed by Selldorf Architects, will include no fewer than 40 exhibition galleries. According to a spokesman for the Rubells, the venue is scheduled to open in 2019—a year later than announced initially.

Facade, Rubell Family Collection, Miami Rubell Family Collection

Mera Rubell, who started the collection with her husband Don (their son Jason and daughter Jennifer are now also involved), says that Wynwood was “factories and warehouses when we moved here 24 years ago”. Moving to a lesser known district changes the art landscape in Miami and presents new challenges. “It is time for us to reimagine our foundation in a very exciting, emerging neighbourhood,” Rubell says.

Tapping the wealth

All three of these projects illustrate the power of private patrons in Miami. Its privately-run museums have flourished since the launch of Art Basel in Miami Beach in 2002. But are there enough wealthy donors to also support the city’s public institutions?

Austin says: “I am sure that all the museums are reaching out to the same donors, since ultimately we still are a small-ish art community and the big collectors and donors are pretty well known —but their kids are up for grabs, I think. The challenge is [identifying] new members and donors who can find something in the museums that resonate with them.”

Franklin Sirmans 2013 Museum Associates/Lacma

Franklin Sirmans, the director of Pamm, says: “There is a lot of wealth here that could still support arts and culture. We are starting from a very different vantage point, financially and geographically. In other cities such as Boston, Chicago, and Houston you will see more family representation on multiple [museum] boards. We don’t have that yet.”

The New York Times reported that Pamm’s expenses exceeded its revenue by $5m in 2015, although its chief Financial Officer Mark Rosenblum says this does not translate into an operating loss, since the museum has broken even or had a surplus in previous years.

Sirmans adds that audience figures are healthy. Pamm is projecting 350,000 visitors for 2017—an increase of nearly 67,000 from the previous year. Its exhibition Julio Le Parc: Form into Action, which closed this March, set a new record for the museum. The show of works by the Argentinian artist drew 132,249 visitors during its four-month run.

The local collector Dennis Scholl also highlights Miami’s unique position and history as an emerging cultural destination. “We are not a rust-belt American city that started collecting in the 19th century. We have to collect art of our time,” he says. “Also, look at some of the city’s museum boards; a large percentage of those trustees did not live here five years ago.”

Dennis Scholl Matthu Placek 2012

In September Scholl was appointed chief executive at the non-profit organisation ArtCenter/South Florida, which is known for its studio residency and outreach programmes (he was also recently appointed to Fairholme Unlimited’s board of directors). Like other cultural leaders in the city, he welcomed Art Basel’s decision to extend its contract with the Miami Beach Convention Center until at least 2024.

But Miami’s standing as a year-round destination for seeing contemporary art rather than just being a hotspot for a week in December when Art Basel descends, remains to be confirmed—at least for some. Scholl says: “The wealth of talented artists in Miami supports the idea of the city being a year-round arts hub. We have a strong dedicated group of collectors, a growing museum group and a community that now views itself as a cultural destination.”

A Miami-based curator, who preferred to remain anonymous, is rather more candid: “Museums must be breathing a sigh of relief—the fair is the great leveller here, thank God it’s hanging around.”