In response to a current exhibition in New York that includes art by current and former detainees of Guantanamo Bay prison, the US Department of Defense has banned all such works from leaving the military lockup in Cuba, pending a review of its policy on the matter. The 41 inmates currently held at the facility—all reportedly on terrorism-related offenses, although only ten have been charged or convicted—will no longer have a claim to the drawings, paintings, wood sculptures and other objects they create in sanctioned art classes that the Obama administration started in 2008. Under the new rule, these works will be the sole property of the US government.

As the Miami Herald confirmed with a spokesperson from the Pentagon, the government’s decision came in reaction to the exhibition entitled Ode to the Sea, currently on view at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York (until January 26), which includes around three dozen sea-themed paintings, drawings and sculptures by eight current and former Guantanamo detainees (four of the men are no longer imprisoned). "It's easier to humanise an image of the sea than it is to humanise the man who painted it. I think that's the power of this exhibition," says one of the co-curators, Charles Shields. "The Pentagon's response has proven how powerful the work is. It proves how powerful art is."

Ghaleb Al-Bihani, Blue Mosque Reflected in a River (2016), made after a terror attack in Istanbul near the Blue Mosque Ghaleb Al-Bihani

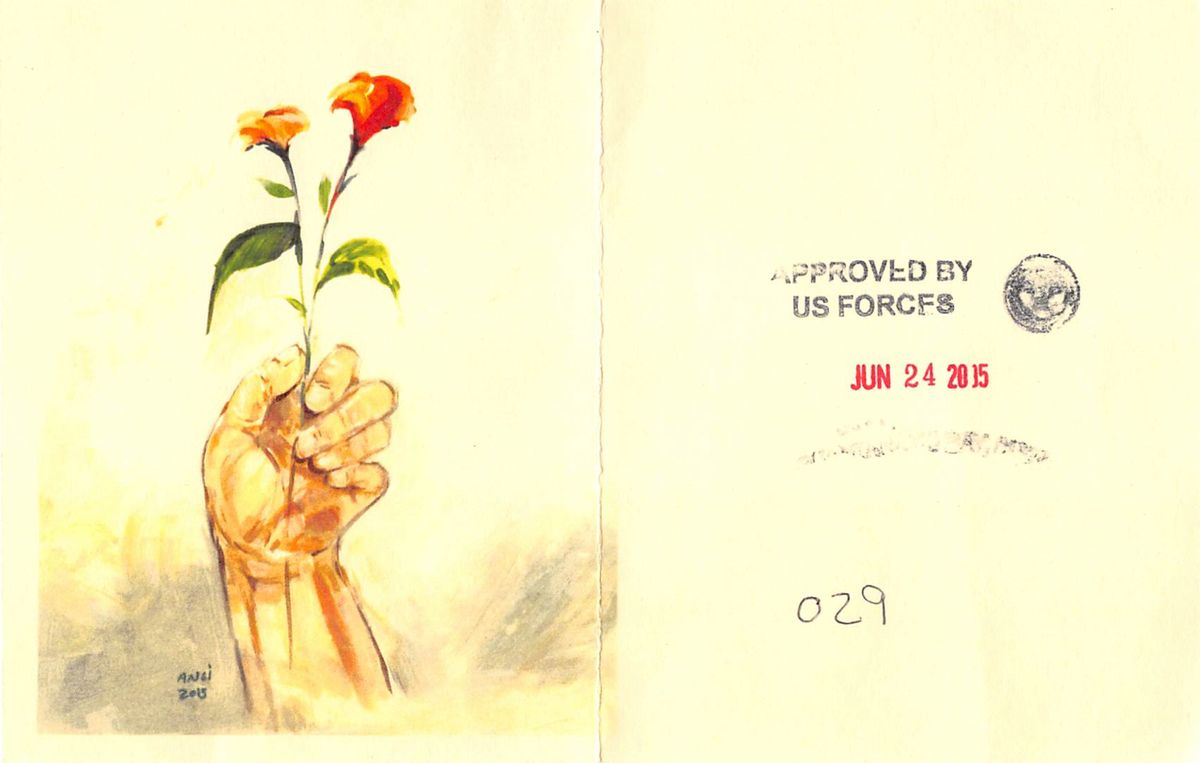

According to the Herald, the Pentagon was specifically troubled by the fact that some works in the exhibition are for sale. However, the organisers say that they are only helping to facilitate the sale of works by those men who have been released and cleared of any wrongdoing. Muhammad Ansi from Yemen, for example, who was held at Guantanamo for 15 years until his release in January of this year, needs the money for his mother's medical bills and other personal expenses, says the show’s co-curator Paige Laino.

While the organisers have circulated an online petition to challenge the Pentagon's decision, they do not have many other options available to them. "It's tough," Shields says, "because there are no legal safety nets in place to protect the civil liberties of these men, and it's unclear what will happen."

The 36 works in the show come from lawyers who typically received them either as gifts or for safe-keeping, but only after they were rigorously screened and approved by US forces. The curators say that many of the pieces are based on images found in National Geographic, one of the few publications available to the inmates, which explains why so many reference American culture—the Statue of Liberty, for example.

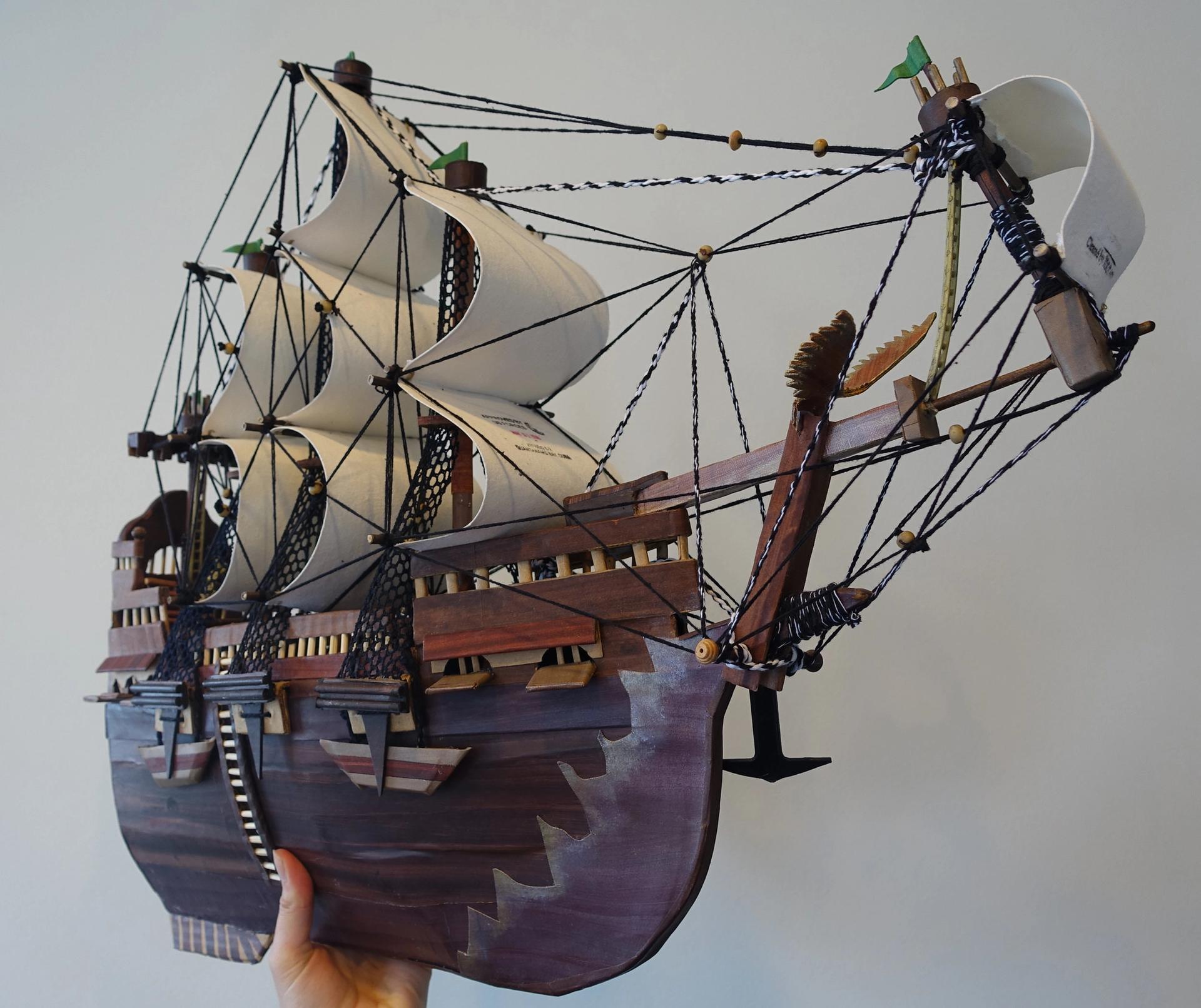

Moath al-Alwi, Model of a Ship (2015) Moath al-Alwi

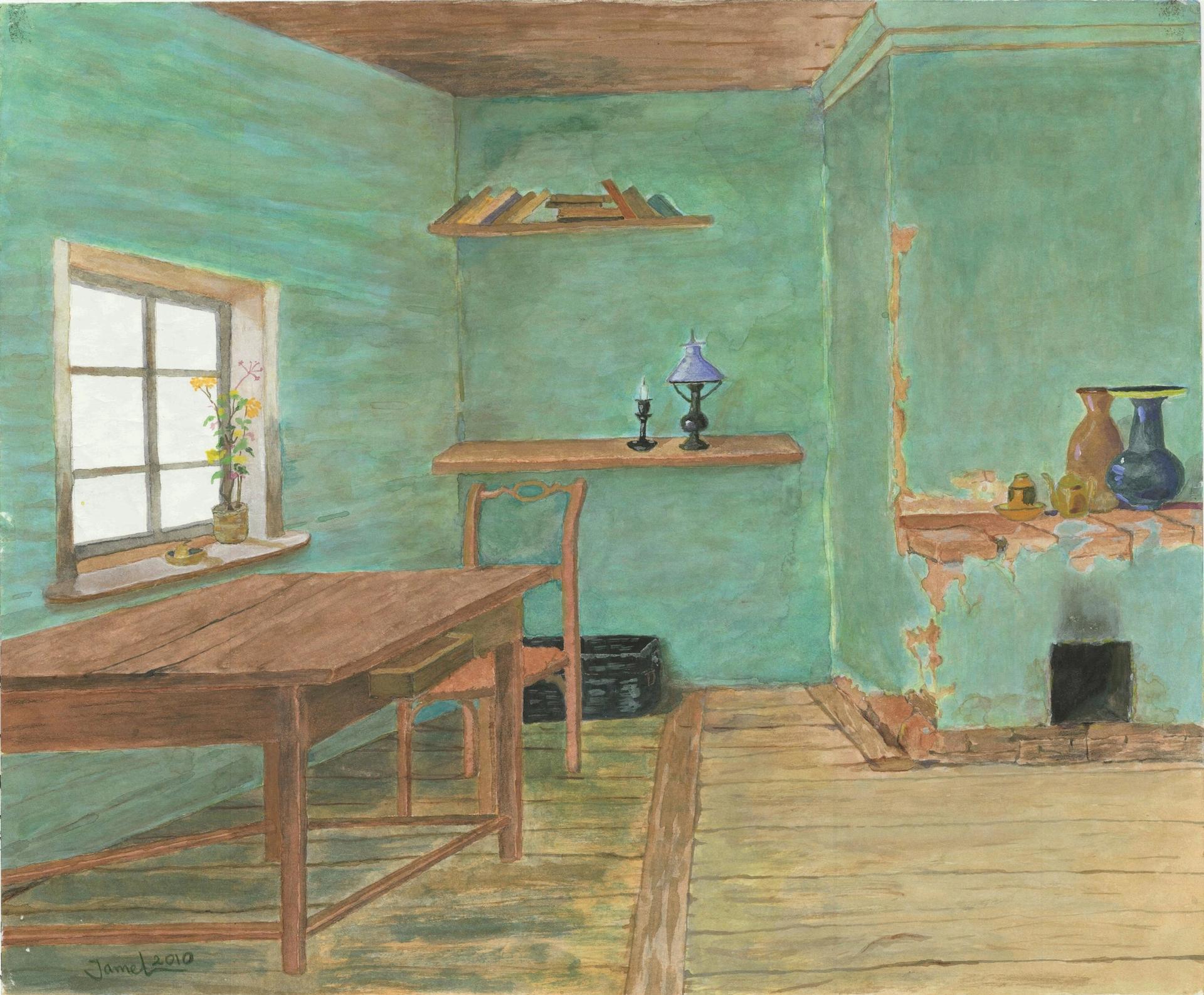

"The instruction portion consisted largely of handing out scans of art history text books (which were not permitted on the base) and having the students recreate the illustrations," explains Laino. One teacher who presided over the art classes between 2009 and 2015 was a Jordanian man named Adam, yet this was not likely his real name. "The classes were intermittent and irregular. And in the time between instruction, detainees who got art supplies through their lawyers would share techniques with one another and build their own sort of art classes. From what I gather, it was sort of a guild, where the artists would make paintings and display them in their cells for all of the detainees to enjoy—hence most of the work adheres to more strict Muslim tenants forbidding the depiction of human figures, as to not alienate the more conservative detainees."

Once it closes at John Jay, the exhibition will likely travel to another venue that remains to be determined, but where it will no doubt continue to generate discussion. "Regardless of what side of the fence you fall on," says Shields, "whether you support or don't support showing this work, I would just ask that people take a look at it."

Djamel Ameziane, Interior (2010) Djamel Ameziane