The documentary Shadowman, which opened in New York today at the historic Quad Cinema, chronicles the career and extended decline of Richard Hambleton (1952-2017), a painter who outlived the notoriety that once made him a star of the downtown New York scene.

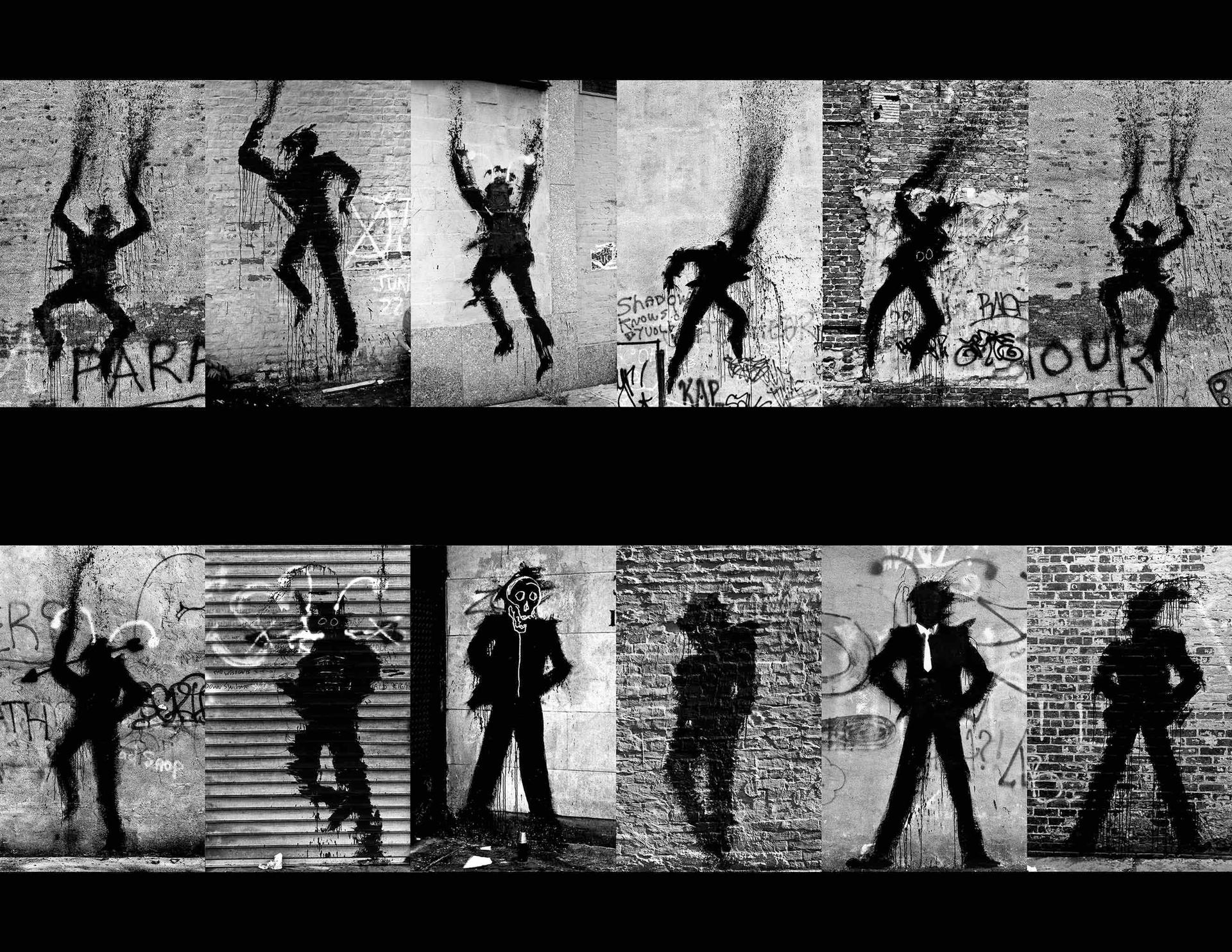

Hambleton, who died on 29 October, was the artist who painted a shadowy, threatening figure in black he called Shadowman on street corners in Lower Manhattan in the 1980s. It brought him international fame as graffiti art became chic. His long fall from celebrity made Jean-Michel Basquiat’s descent into drugs and neglect seem graceful.

In Oren Jacoby’s film, Hambleton’s career misfortune was that he had far more than Andy Warhol’s allotted 15 minutes of fame—he lived almost 30 more years after the heyday of the East Village. Or as the artist puts it on camera: “At least Basquiat died. I was alive when I died, that’s the problem.”

The film looks back to the 1970s, when Hambleton founded an alternative art space in Vancouver. His signature works then were outlines of would-be corpses on the street, painted at night. “They’d wake up and think, who died here?” he says in an interview.

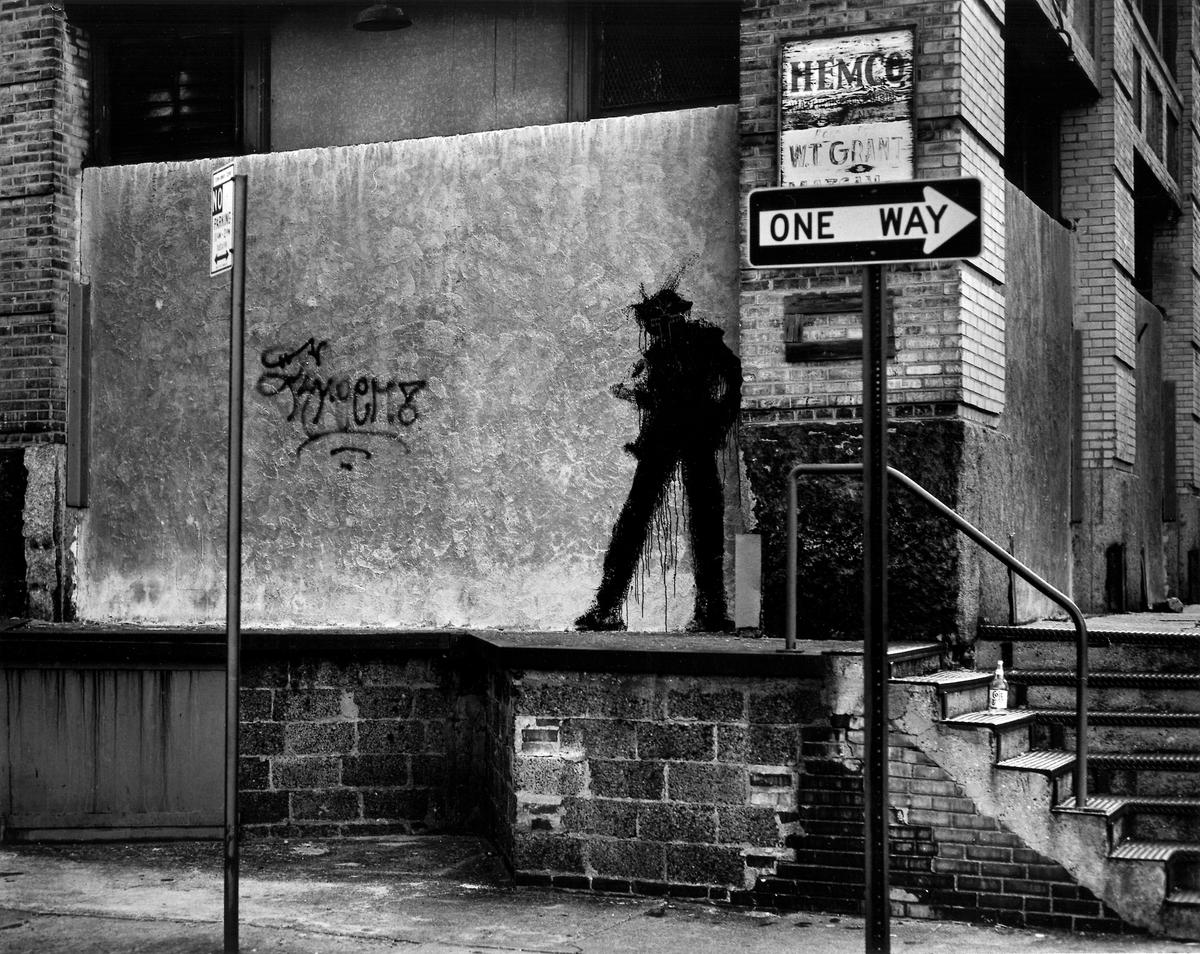

Night-time footage in the film shows Richard Hambleton splashing a Shadowman onto a wall in a minute Photo: Hank O’Neal. Courtesy of Film Movement, Storyville Films and Motto Pictures

When he first moved to New York, the ever-smiling well-groomed Hambleton was more acclaimed than Basquiat or Keith Haring. Night-time footage shows Hambleton splashing a Shadowman onto a wall in a minute. Although his street work was public—and unsellable—he soon made Shadowman paintings for the market. But he tired of those images and turned to fiery landscapes and frothy seascapes, which the market didn’t want.

He also collected works by his peers, and sold that work at rock-bottom prices to feed the heroin habit that put him near death many times over the decades. “Meet me at a cash machine,” he was known to say over the telephone. Later on, untreated skin cancer would eat away at his face. After the 1980s, when Hambleton’s name came up, a frequent response was: “Is he still alive?”

Richard Hambleton with one of his paintings Photo: Hank O’Neal. Courtesy of Film Movement, Storyville Films and Motto Pictures

Yet Hambleton kept painting, even while homeless or crashing in storage spaces with junkies and prostitutes. And dealers still tried to salvage work from him, although Hambleton, whom we see roaming through framed canvases, was loathe to part with anything. Giorgio Armani tried to monetise him in 2009 with a global marketing campaign, but the dealers tasked with managing the artist found him uncontrollable. A pop-up exhibition at the film’s spring premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival drew a huge crowd, with a ravaged Hambleton attending in a wheelchair.

Unfortunatlely, while would-be dealers and fellow junkies sing his praises (and catalog his pathologies) in the film, there is no extended interview with the artist and no critics cite his enduring influence. Hambleton gets one last laugh, though. A 1982 canvas of Shadowman that is almost nine feet tall is a hit in MoMA’s current exhibition devoted to the East Village art space Club 57.