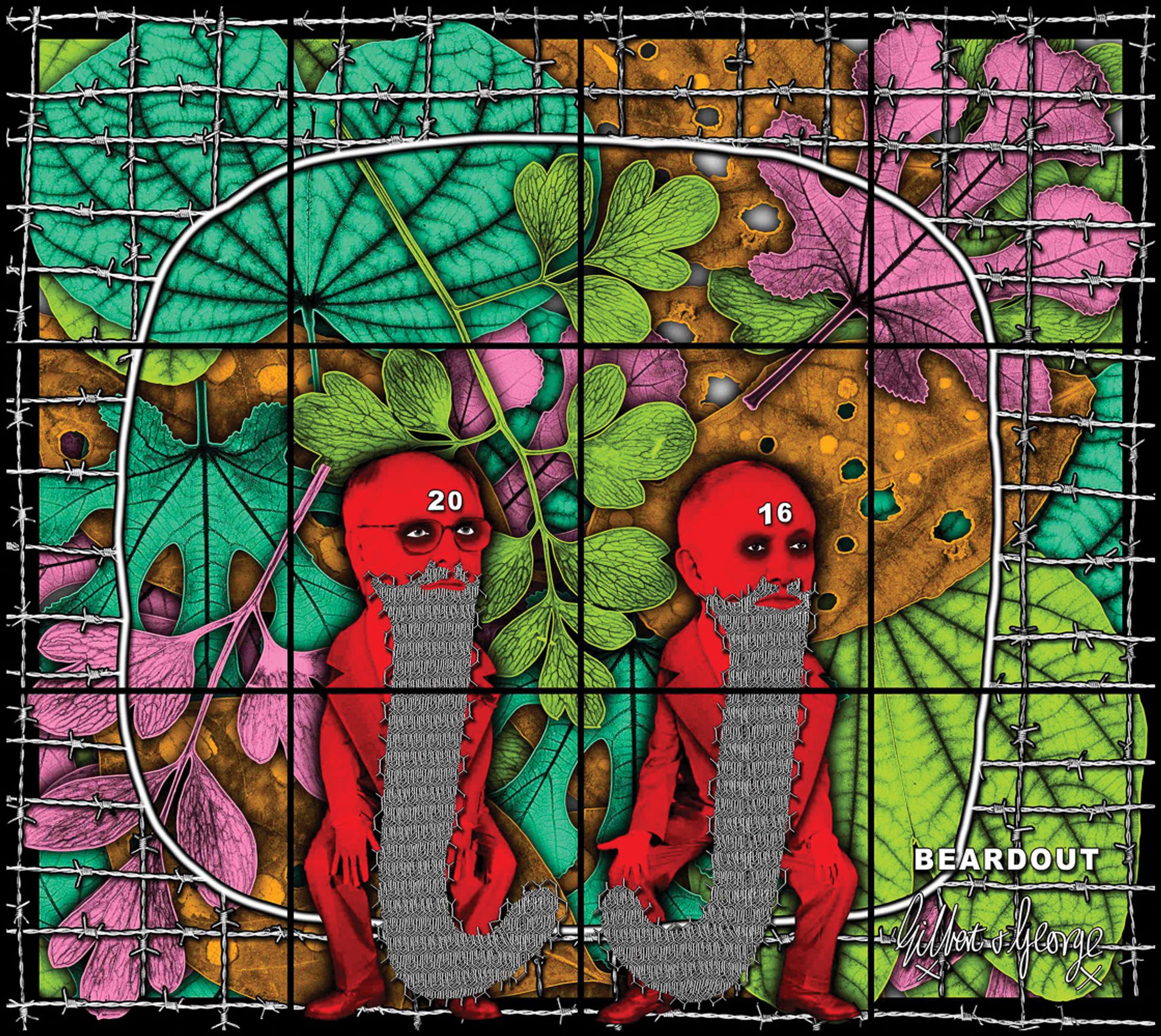

The art world’s best-known and longest-running double act celebrate half a century of living and working together as “living sculptures” this year. To mark the anniversary there are eight new Gilbert & George exhibitions taking place in New York, London, Paris, Brussels, Naples and (in January) Athens. Each show presents a different version of The Beard Pictures, a new series of their trademark “photopieces” in which the hitherto clean-shaven duo appear red-faced and sporting mask-like beards and moustaches made mainly from leaves and barbed wire, as well as a bizarre range of other materials including beer froth and rabbits with forked tongues. At White Cube in London, these multipanelled photographic works are being shown alongside The Fuckosophy, an epic text work comprising 5,000 statements, slogans and mottoes all of which incorporate different uses and variants of the F-word. They are also looking to their legacy with a plan to establish a foundation devoted to their work, situated near their studio and home in east London, which they aim to open in the next two years.

The Art Newspaper: These shows celebrate the date—in 1967—that you first met at St Martin’s School of Art and decided to work together. How did it happen?

George: It was this strange thing of us coming from the ends of the world: me from Devon via Oxford and Gilbert from Italy through Germany. It was quite magic that it worked in that way. St Martin’s was the place to be at that time—but just the sculpture department, not the rest of the college.

Gilbert: For me, it was like landing on the moon. From a village in northern Italy, then from Munich to London. I couldn’t speak the language, but St Martin’s was famous—and I had the extraordinary idea to want to be there.

“Beards are very up-to-date today. We have a Fuck off Hipsters Beard Picture”

What attracted you to each other?

Gilbert: Ask George; he was the one who took me around.

George: We realised that we were different from the others, because most art students are middle class and they don’t have too many worries—they can always fall back on Dad, or go and run the pig farm, or something. We were both country bumpkins and we didn’t have that. We knew that if we didn’t become artists we would be finished—we had to succeed. Of course, the big anniversary is really 1968-69, when we did the first work of art together [George the Cunt and Gilbert the Shit], which was shown for one day in Robert Fraser Gallery and published in Studio International with the so-called offending works blocked out.

What made you decide to work together?

George: I don’t think we ever made the decision, it was something that came over us, it just happened. It was the whole idea to remove ourselves from the art of the tutors and the students, which was formalistic art. It was all to do with shape and colour, and we wanted to say, why can’t art involve thoughts and feelings, and love and dread and fear?

Gilbert: And drinking. We had this extremely crazy idea that we could be the artwork ourselves. We were walking the streets of London because we didn’t have a studio, but we still wanted to be artists. This was why we used to send out these little letters, to tell people what we were doing: that the snow was falling, that we made a cup of coffee—to make ourselves the artwork.

What about contemporaries like Bruce McLean and Richard Long, who also made live work?

Gilbert: They were still doing art about art and we never wanted that—we wanted to make art about life.

George: We realised that the tutors and the students had this idea that they were superior to the public—that everybody out there is stupid and only us in the art world know anything. And we didn’t like that. We just wanted to humanise everything, it was very simple.

Gilbert & George. Courtesy of White Cube

Where do The Beard Pictures come from?

Gilbert: We started to distort ourselves a long time ago with the Jack Freak pictures in 2009 and then we did the Scapegoating pieces [2014] and they were all masking ourselves back and forward, being in front of people and behind them in some way. Now we are seeing the whole world through a beard. Good beards and bad beards, religious beards and non-religious beards. If you are Jewish, Islam, Sikh, you are not allowed to cut the beard. And that interests us because they are all fencing each other off.

George: Immigrants and all that stuff. Barbed wire was to do with farming when I was a child, nothing else—for sheep, not humans.

In The Beard Pictures, your beards are often made of barbed wire and appear fenced in.

George: I see it as an exploration of our modern times. You switch on the news and you see barbed wire and bearded people. We are making the beards make everything for us, past, present and future. The most famous beard in the world? Jesus! When I was a teenager you wouldn’t get a job if you had a beard and if you were in the armed forces you could only have a beard if you were in the navy. Queen Victoria made her son grow a beard to be more modern and even Dickens got himself up to date with a beard. And of course beards are very up to date today. “Fuck off hipsters” is written all along Brick Lane—it’s class war. We have a Fuck off Hipsters Beard Picture.

It’s often unclear whether you are celebrating or criticising what you depict—is this deliberate?

Gilbert: It has to be aggressive in some way: we are provoking thought. We invented a new way of making pictures for ourselves that can speak very loudly and confrontationally. We are pressing buttons.

How did you choose the 5,000 statements of Fuckosophy?

Gilbert: We started five years ago—I think we heard the builders next door through the wall.

George: It [the word fuck] is so boring because it’s always used against cars or by builders talking about “the fucking bricks”. We want the real thing that’s inside everybody’s heads. We all know what philosophy is, we might even have a book or two—but this you can understand. We did a Fuckosophy reading in Tasmania and half the people were amused by it and worried sick why the other people weren’t, and the other half were not amused and worried sick that they were not like the other ones. And that is the perfect response—they can figure it out. After we finished the Fuckosophy, we thought, there is nothing else in the world that is as interesting. And then we realised there is something else: religion. So now we are doing the Godology, which should be amazing.

Will it be in the same format: open-ended lists of statements about God?

George: Yes! [reads from a list] The God news, God goes away, please stand for God, God’s a sissy, God stinks, God licked me, God and the scaffolder, God’s no toff… Whatever people say about it, they will be right. If they say it’s horrible, then we will say, yes, religion is horrible. If they say it is silly, we’ll say, of course, religion is silly—you’re right every time.

Gilbert: Ban religion is our motto.

George: Religion would be fine if it came under the same legal umbrella as ourselves. If the Trades Descriptions Act and everything else applied to religions and they didn’t have any opt-out, it would be better for them and better in general.

You are converting a former brewery near your house and studio in East London into a foundation, funded by you and devoted to your work. What made you decide to do this?

George: When we were students the Tate always had at least one work of every living artist on show; that was their remit. But they’ve stopped doing that now. So if somebody arrives from Venezuela this morning and wants to see a work of ours, there won’t be one at the Tate.

Gilbert: Shows will change twice a year and if we have enough money, we can show other people too if we want.

Will it be free entry?

Gilbert: It will be about five quid, I think. We don’t want every tramp to go in to use the toilets.

Doesn’t that sit a bit uncomfortably with your motto of Art for All?

George: Ideally, we would like it to be free, but it may not be practical.

Gilbert: They have to want it in some way, we don’t want anybody just walking in and out like it is all open fields.

Will the foundation continue when you are no longer with us?

George: Yes, we have trustees and it is a registered charity. It will be G&G forever, like we all want, of course.

• Gilbert & George: the Beard Pictures and Their Fuckosophy is at White Cube Bermondsey, London, 22 November-28 January 2018. Visit the artists' website for details of the seven other exhibitions featuring The Beard Pictures, held at their galleries in New York, Paris, Brussels, Naples and Athens between now and February

Three Key Works

Gilbert & George. Courtesy White Cube

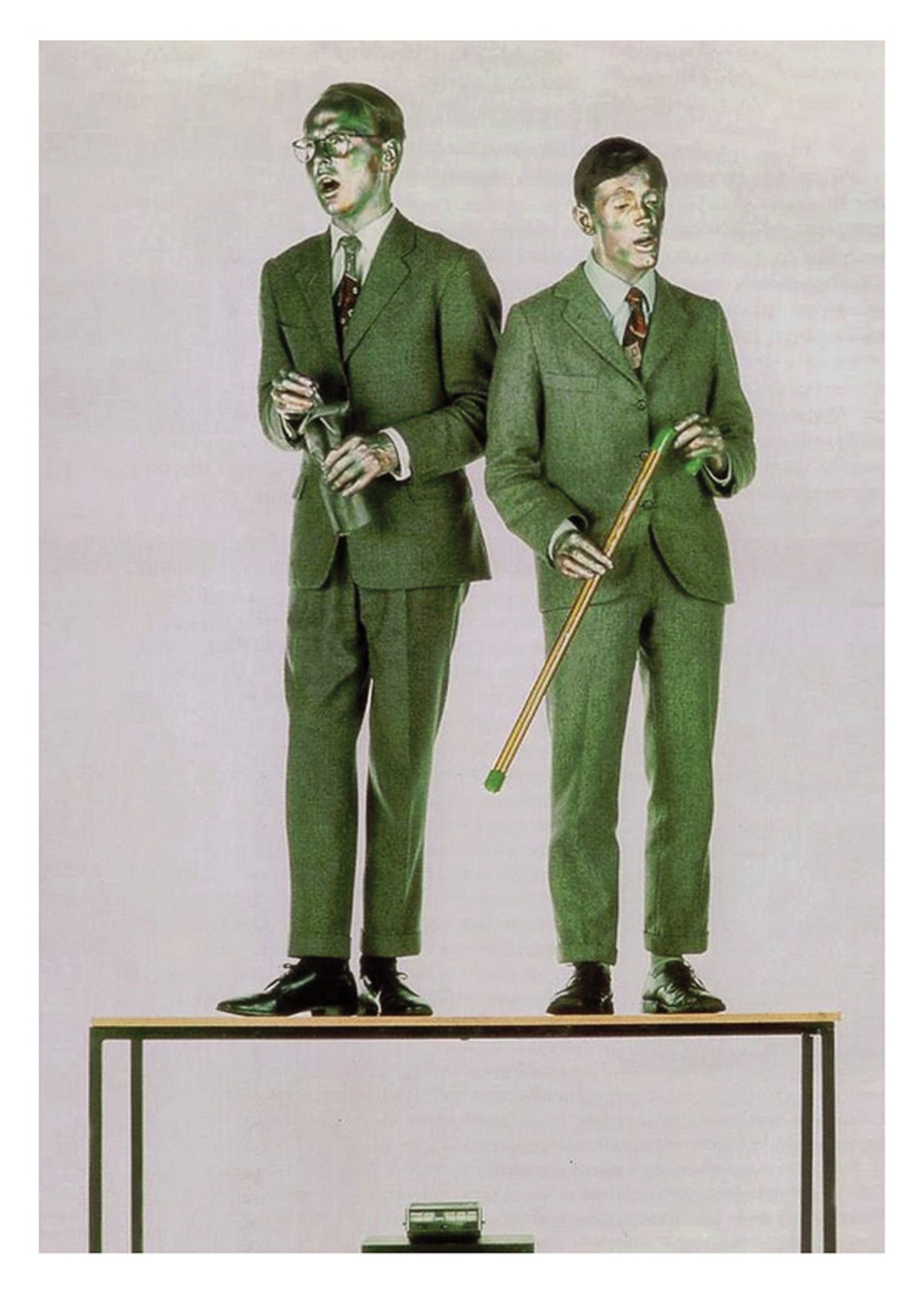

The Singing Sculptures (1969)

The work which launched Gilbert & George as “living sculptures”. They have described it as “G&G’s first work”. They add: “It was no longer a collaboration. We were on the table as one and the same sculpture. A sculpture composed of two men. Inseparable.” It is a live work in which they repeatedly sing Bud Flanagan and Chesney Allen’s classic music-hall song Underneath the Arches, often for hours on end, while moving robotically, with their hands and faces covered in metallic paint. First performed literally underneath the arches, both in Charing Cross and Cable Street, east London, it has been repeated many times since in venues around the world.

Gilbert & George. Courtesy of Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac

Drinking Sculptures (1971-72)

After selling their first work in 1970, the duo celebrated by getting drunk and recording the experience in photographs. These Drinking Pieces led to the Drinking Sculptures, a reaction against what they saw as the elitist restraint of minimalism. “Artists would get smashed at night, but in the morning they would go to their studio and make a perfect minimal sculpture,” they once stated. “They were alcoholics but their art was dead sober. We did the Drinking Sculptures as a reflection of life.” G&G are pictured with the video Gordon’s Makes Us Drunk (1972) and the works Twelve Noon (1973) and Toy Wine (1972), in Gilbert & George: Drinking Pieces & Video Sculpture 1972-73, at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London.

Gilbert & George. Courtesy White Cube

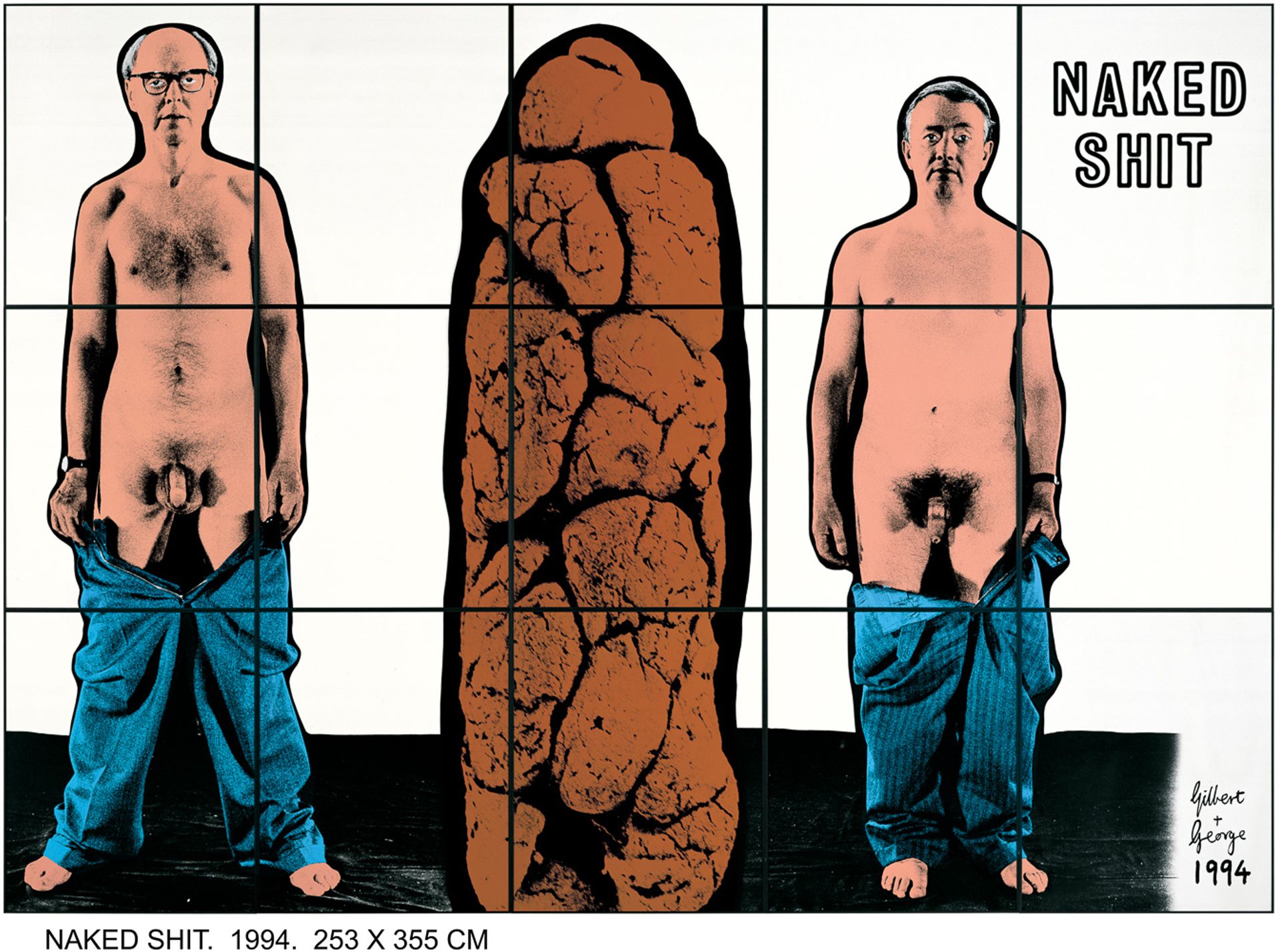

The Naked Shit Pictures (1994)

These coloured photopieces, featuring the artists without their customary suits and accompanied by giant pieces of their own excrement, are among their most provocative and taboo-busting works. They were shown at the South London Gallery in 1995 and Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1996. “For us, being naked in front of the public, we are trying to make ourselves vulnerable in front of the viewer,” they have said. “We don’t believe that there is anything wrong in doing pieces to do with shit because shit is part of us.” Pictured is Eight Shits (1994).

Biography: Gilbert & George

Background: Gilbert Prousch was born in 1943 in San Martino, a Ladino-speaking village in Italy’s Dolomites. He says of it: “Being so cut off from the rest of the world marks you for life.” George Passmore was born in 1943 in Totnes, Devon, and says his mother wanted him and his brother “to be different from other boys our age… we read books from the turn of the century and listened to records from the turn of the century.”

Education: George studied at Dartington and briefly at Oxford technical college before enrolling at St Martin’s art school. Gilbert attended art schools in Wolkenstein in South Tyrol, in Hallein in Austria, and in Munich before starting at St Martin’s in 1967. There he met George, a third-year student by then, who described it as “love at first sight”. Gilbert remembers George as “an eccentric aesthete, free and glamorous”. When George left St Martin’s, Gilbert went with him.

Milestones: Their first fully collaborative work, George the Cunt and Gilbert the Shit, was exhibited in 1969 at the Robert Fraser Gallery, London. Also that year, they presented The Singing Sculpture (see Three Key Works), the work with which, in 1971, Ileana Sonnabend invited them to open her New York gallery. The same year, their first solo museum show opened at the Whitechapel Gallery, and photography became their principal medium. Major shows since then have included those at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in 1981, and the Guggenheim Museum in New York, in 1985. They won the Turner Prize the following year. They showed early in cities previously inaccessible to Western artists, such as Moscow in 1990 and Beijing in 1993, and represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 2005. They are the only living artists to have filled an entire floor of Tate Modern, with their 2007 retrospective.