Igor Tsukanov wants us to get a sense of the tension, peril and shock involved when a performance artist does something extreme in Russia to protest against the status quo. For while they are fairly unlikely to die, as in Stalin’s day, they may well go to gaol, and they definitely risk the strong disapproval of a population that knows little about contemporary art and meticulously avoids rocking the boat.

Courtesy of the Tsukanov Art Collection

The exhibition Art Riot will be performed as well as hung on the walls, and we will be invited to participate because, for Tsukanov, this is not just an art exhibition but an opportunity to raise awareness of how awful Russia has become: “If you want to destroy a country, appoint a president like Putin,” he says.

A London-based banker who retired early to develop art projects, Tsukanov has always been interested in the art that has stood out against the regime. In 2012, he wanted to stage an exhibition in London on unofficial Moscow art from the 1960s to the 1980s but had no response from the museums he approached. Then he got a call from the Saatchi Gallery, which had seen the presentation, liked it and suggested a collaboration. The resulting show was called Breaking the Ice: Moscow Art 1960-80s, and it attracted more than 600,000 visitors. This and the following two shows have probably been the most original, intelligent and relevant shows the Saatchi space in Chelsea has held. The partnership between Saatchi and Tsukanov lasts until 2018, and the aim is to do exhibitions on the Soviet Union, Russia and Eastern Europe. This is the fourth, while the fifth and last, in two years’ time, will show art from the Caucasus, combining some of the former Soviet Republics: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Dagestan and Chechnya.

Dealing with Actionist artists is not without its challenges. One of his three stars of the Saatchi show, Pyotr Pavlenksy, was arrested last month after setting fire to the Banque de France in Paris.

The Art Newspaper: Is it a coincidence that Art Riot: Post-Soviet Actionism, which is pretty subversive stuff, is happening around the anniversary of the 1917 Revolution?

Igor Tsukanov: I definitely thought about the anniversary. This exhibition doesn’t have a direct link to the Revolution of 1917, but the atmosphere in 1916 and 1917, of something about to happen—artists felt it, musicians felt it—is like what you feel in Russia today. It has reached a point with the government and President Putin that something needs to be done urgently. Artists started doing these performances ten years ago to wake up society, to say: “Something bad is going on.” The performances relate to the political regime, the religious oppression and the general lack of freedom.

Why do you think the 1917 Revolution is being commemorated in Russia by exhibitions about the Romanovs?

I think it’s because Mr Putin doesn’t like the Russian Revolution. Even though he was a KGB officer, he believes that communists are crazy guys, so he prefers to be associated with the big history of Russia: the great empire, the Russian imperial family, this kind of stuff. So those who do these exhibitions about the Romanovs know that the minister of culture will be pleased. Exhibitions about the actual Revolution need to find private support. By the way, the minister of culture, Vladimir Medinsky, has said publicly—it’s his motto—addressing the movie directors: “If we, the Ministry of Culture, finance you, you will do what you are told to do.” He thinks it’s the minister of culture’s money, not the taxpayers’ money.

Actionism is usually performance art. What kind of performances is this exhibition about?

It’s a documentation of the live events that took place in the streets of Moscow and St Petersburg, on Red Square, and at the Lubyanka [the Federal Security Services HQ], where Pyotr Pavlensky set fire to the front door of that symbol of power. That was filmed by almost 20 cameras from all angles, and when he was put on trial, the Security Services assembled all the videos, so Pavlensky said: “By my performance, I forced them to produce my own art.” That was very funny.

I want to bring this into the Saatchi Gallery, with videos and visuals, but also live performances produced or performed by professional artists, especially Pussy Riot, who will give a theatre-type performance of 20 minutes in which visitors are expected to wear balaclavas so that they get the feeling of being in front of Red Square, exactly as Pussy Riot did it years ago.

Which artists are you going to be showing?

Pyotr Pavlensky, Pussy Riot and Oleg Kulik are the main ones, and they are coming to London for the opening and media presentation. Others are the Blue Noses Art Group, Arsen Savadov, AES+F and Vasily Slonov.

Has the subject matter of their performances changed since the end of communism in 1991?

Definitely. Oleg Kulik, who was one of the first performance artists and the father of Actionism in the new Russia, started in 1992, when he made one of his most famous performances. He played a dog that was surrounded by people but felt uncomfortable as a dog. It was a reference to the fact that in the new Russia, with the new capitalism, there was a collapse of the social regime and people felt very insecure as they were forced to move from the collective type of habitat to the completely individual habitat, where everyone is on his own. Another performance by Kulik was I Bite America and America Bites Me. This was in New York, the heart of capitalism.

These artists are now the mainstream of Russian art of the past 20 years, not something marginal

At the end of the 1990s, Kulik dropped his performances because he felt the subject matter was not relevant any more as the economy had grown. Once he stopped, then other artists who were young at the time started feeling that something had happened in the country. This was not about the economy, not the individual versus society, but about society going through major changes because of the new regime under Putin. He gradually started changing the vector of the country’s future from a capitalist, free-market economy with the freedom to write, the freedom to perform, to so-called state capitalism, which is controlled by the government. They control not only the economy, but the freedom of expression and the press. The media was taken over by the government, and in the Church, the priests stepped in with their own paternalistic ideas.

So the artists started making performances that they aimed at the political and religious suppression in society in the hope that it would be like a bell—they really wanted to ring the bell, to tell people: “Something is going on here; you are not free any more.” This was threatening to the system, so Pussy Riot was jailed, Pavlensky was put on criminal trial, and some other artist groups left the country after they were followed by the KGB.

These are performances that have gone on over 15 years and it has been pretty dangerous for the artists in Russia. I really want to give visitors to this exhibition a feeling of how difficult it has been and why these young men and girls started to put themselves on the frontline.

Did you manage to get anybody to help you sponsor this expensive enterprise?

I have my usual sponsor, my old friend Leonard Blavatnik with his foundation. He’s supported all my exhibitions. But some other sponsors who used to help me, my friends who have businesses here and especially in Russia, have said: “Look, we know what you’re doing; we support the show. We’ll help, but anonymously.” But I appreciate this very much too.

The myth of the artist in the 20th century is that he or she has to be a prophet, a rebel, a critic of society, and some artists have indeed been very brave. But in the West, some artists have become soft; the market is consuming them. Do you think that seeing these brave artists working in very difficult conditions will be inspiring for the British art public?

I agree that artists now are more soft because of the market. But I think sometimes it’s a matter of the subject they focus on. Just an example: a few years ago, there were the riots in Greece, in Ukraine, even in the UK, tragic events, so the British artist Marc Quinn produced a beautiful set of paintings [History Painting, 2011 onwards], in which he represented what he saw in the press—a very powerful series. I wouldn’t say it’s British art, because it’s so powerful. Of course, British society is now also divided by Brexit and a great sense of insecurity. You feel it as well, right? The artists can’t avoid it either, so I expect Brexit will be part of the new art that is coming soon. But unlike Russia, no one here puts artists in jail if they touch on a sensitive subject. In Turkey, there are a few artists who produce work on very sensitive subjects because of what’s happening there, and in America everything is getting more and more polarised. The artists will feel it and produce art about it.

What is the after-life of this exhibition going to be?

We are producing a catalogue that is not just the book of the exhibition but that aims to be a reference work for future scholars. Boris Groys of New York University has contributed to it, and there is an article by Natalia Murray of the Courtauld Institute [curator of Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932 at the Royal Academy early this year] about performance art during the 1917 Revolution, and many other scholars.

We have plans to bring the exhibition to other places and it should be easy because most of the art has been commissioned by me, so it will be kept in London in storage and can be shipped to wherever there is demand for it. You know, in terms of the exposure to the media, there have been thousands of articles around the world about these artists. Penguin books has just published Riot Days by Maria Alyokhina, who is a founding member of Pussy Riot, and there was an interview in the Economist a couple of months ago on Pyotr Pavlensky, about whom the New York Times is preparing a huge report. These artists are now the mainstream of Russian art of the past 20 years, not something marginal.

In the circumstances, in Russia, either be brave or be silenced. That’s it. There’s no middle ground.

I imagine it hardly needs to be said that this exhibition could not happen in Russia.

No, it couldn’t happen in Russia.

• Art Riot: Post-Soviet Actionism, Saatchi Gallery, London, 16 November-31 December

The Three Key Artists

Courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery

Oleg Kulik

Kiev-born Kulik is most famous for his performances, in which he stripped naked and became a dog, barking around cities and in galleries on a leash—he even bit an art critic in one performance. He has also appeared as a human glitterball, including in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, standing on a trapeze above the audience covered in shards of mirrored glass

Image courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery

Pussy Riot

The punk band who became an emblem of Russian activism in 2012, when their performance in their customary balaclavas in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, protesting the connections between Putin’s state and the Russian Orthodox Church, led to the arrests of three members and the imprisonment for “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred” of two of them. Pussy Riot have many more members and are linked to the performance art group Voina, who famously painted a penis on the tarmac of the rising and falling bridge opposite the Russian Security Service building.

Courtesy of the Saatchi Gallery

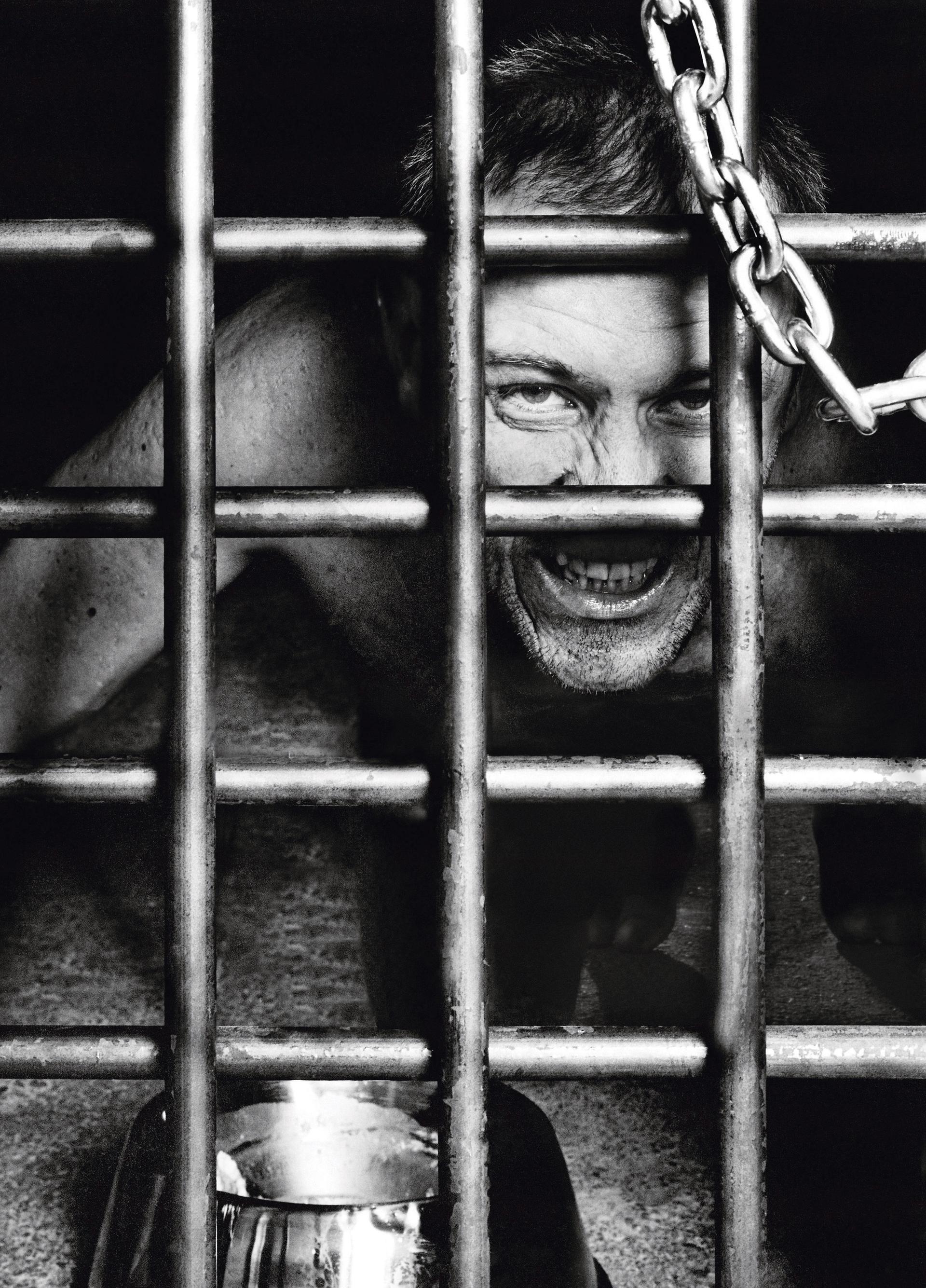

Pyotr Pavlensky

If Pussy Riot performed the action that most powerfully symbolises activist art in Russia today, Pavlensky created its defining image: he sewed up his mouth with red thread. He has also nailed his scrotum to Red Square’s cobblestones, a protest against the apathy and fatalism of Russian society. He fled Russia after setting fire to the door of the Federal Security Services building in 2015. And on 16 October this year, he set alight the windows of the Banque de France in Paris. B.L.

Revolution shows in Russia

Someone 1917, the State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

A look into the minds of artists in the revolutionary period, featuring both avant-garde abstraction and more conventional figurative works.

Until 14 January 2018, tretyakovgallery.ru

The Winter Palace and the Hermitage in 1917, State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

The State Hermitage’s year-long commemoration of the Revolution has focused on the tsar and his family, staged in the buildings in which many of the events happened.

Until 4 February 2018, hermitagemuseum.org

Cai Guo-Qiang: October, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

Revolution-themed commissions from the Chinese artist, including a vast installation involving cradles and birch trees and a video of his Red Square fireworks spectacular.

Until 12 November, arts-museum.ru

Alexander Palace in Tsarskoye Selo and the House of the Romanovs, State Museum Reserve, Tsaritsyno

A multi-part exhibition, culminating in the events around the Revolution and Nicholas II’s abdication.

Until 15 January, tsaritsyno-museum.ru

Exhibitions at the Russian Museum, St Petersburg

Four Revolution-related shows at once: Dreams of Universal Flowering explores the diverse art from the first two decades of the 20th century, Art into Life analyses propagandist decorative art, a further show is dedicated to revolutionary posters, and a display features 100 images of children made in the Soviet Union between the 1920s and 1980s.

Posters of the Revolutionary Era until 6 November; all other shows until 20 November, en.rusmuseum.ru

Ben Luke and Anna Drozhzhina